You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

Beginning in the late 1930s, the RPCNA Synod began a debate regarding the relationship between the Christian and alcohol, a debate that led to a decision 60 years later to reverse its stand against the use of alcohol by its ministry and members. That discussion formally began through the quiet work of J.G. Vos.

Personal History and Exceptions

J.G. Vos was raised in the Presbyterian Church in Princeton, N.J. His father, Geerhardus Vos, was professor of biblical theology at Princeton Seminary and former pastor of a Christian Reformed Church (CRC) in Grand Rapids, Mich. J.G. Vos came to love the singing of the psalms of which the CRC had a strong tradition at that time. And Vos decided that as a future pastor he wanted to serve a church that “adheres to Scriptural worship, particularity in the matter of Psalmody” (Owen F. Thompson, Sketches of Ministers, 344).

Besides psalmody, Vos also chose to enter communion with the RPCNA because of the “exclusion of oath-bound societies” (secret societies), “maintaining strict discipline over members” and because of “Calvinistic theology and a Reformed view of life.” Each of these reasons led Vos away from the CRC and the Presbyterianism that was crumbling in the mainline denomination, and into the RPCNA.

J.G. Vos studied at Princeton Theological Seminary where he earned his divinity degree. He then spent a year at the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (RPTS) meeting the recommended requirements for RP students of theology. Vos was licensed to preach the gospel on May 23, 1927, by the Philadelphia Presbytery. He was then ordained to the gospel ministry by the Pittsburgh Presbytery on Mar. 25, 1929, and installed as the pastor of Miller’s Run RPC in Cecil Township, Pa.

At both his licensure and ordination, he took exception to Vow 8, which required him “to abstain from alcoholic beverages and habit-forming narcotics.”This does not mean that Vos partook of alcohol and drugs; it merely means that Vos did not believe that this was a biblical requirement for ordination.

Vos took exception to Vow 8 both times by stating, “I do not consider the use of wine or intoxicants evil inherently, or per se, but only under certain circumstances or when used in excess.” He went on to say that he believed the church had exceeded its authority “by going beyond the Scriptures and forbidding to church members all use of something which is not inherently evil when the Scriptures forbid not all use, but only excessive use or use under certain circumstances.” His exception was noted and Vos entered the ministry of the church keeping his scruples quiet.

A Short Walk from Temperance to Abstinence

How did the church get to the point where abstinence from alcohol use was required for members and ministers? Vos, as an outsider, came into a church culture that was not present in the other Reformed communions with which he was a part. Neither the Presbyterian Church nor the Christian Reformed Church had such a tradition. It was not always so in the Reformed Presbyterian Church either.

What began as a need for temperance among the ministers ended with a requirement for full abstinence by all under the church’s care. In 1801 an RP minister was deposed for drunkenness following discipline in 1777 and 1785 for the same sin. In 1821 another RP minister was likewise deposed. This led to a culture of caution in the use of alcoholic beverages. If a church’s ministers are getting drunk, the piety of her people may not be much higher.

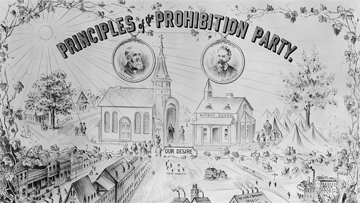

In 1830 the Temperance Society of Pittsburgh approached the RPCNA Synod to issue a statement, and the Synod resolved that they “approve highly of the cause of temperance and recommend it to all under their care.” In 1830 the move from temperance towards abstinence began in the RP Church. By 1857 the church declared that the use of alcohol as a beverage was an offense that could be disciplined. This did not include wine in the Lord’s supper or alcohol for medicinal purposes. In 1883 the views against alcoholic beverages were incorporated into the RP Testimony. By 1906 the Synod formed a “standing committee,” meaning that each year Synod would hear about abstinence, the temperance movement, and the progress of efforts against the sale, use, and promotion of alcoholic beverages. What began as a call for temperance—which means moderation—for ministers, ended with a standing committee on abstinence forbidding any use of alcohol in the life of the Reformed Presbyterian, whether a minister or lay member.

A Few Years of Frustration: 1934-1940

It was already noted that in 1927 and 1929 J.G. Vos took exception to the RPCNA’s requirement of abstinence from the use of alcoholic beverages. This exception grew stronger as he began his missionary work in Manchuria in 1931. As Vos ministered among Chinese Reformed Presbyterians, he saw a difference in the use of alcohol in Chinese culture compared to the broad abuse of alcohol in American culture that led to the 18th Amendment, Prohibition, in 1920. Vos noted that “the Chinese were temperate people, as far as the use of alcohol was concerned.”

In a private letter concerning Vos’s views on the temperate use of alcohol among the Chinese, Rev. F.D. Frazer of the Portland, Ore., congregation, wrote to another RP minister, “I realize to demand total abstinence of the Chinese and Japanese, in their present state, is to demand something that is hard for them to understand; about as hard I imagine, as it would be for us to be told that we must totally abstain from caffeine drinks such as coffee, tea…and Coca-Cola.”

The fact that the Chinese were not given to drunkenness, according to Vos, led him to write to the Synod in 1934 asking a number of questions concerning the RPCNA’s stance on alcohol use. Vos submitted a 7,500-word paper (this would equal 30 pages, double spaced) to the Synod in 1934. The paper was divided into three parts. The first part explained how the Scriptures do not require total abstinence from alcohol. The second part challenged the notion that a Christian church may make total abstinence a requirement for fellowship in the body. In this section, Vos went as far as saying that it was “schismatic” and that such a requirement “injures the unity of the body of Christ.” The third part of the paper Vos called supplemental and dealt with miscellaneous concerns ranging from the ancient Gnostics’ view of wine to the then-current practices of the Chinese people.

The 1934 Synod took up Vos’s paper, which is filled with exegesis of biblical passages dealing with alcohol. Synod received the paper and referred it to the professors of RPTS. At the 1935 Synod, there was no response to the paper by the professors, and it was forwarded to another committee. That committee reported in 1936 and gave a 63-word response to his 7,500-word paper. In the response, Synod “would re-affirm its faith in that section [of the Testimony] as it stands.” Vos’s concerns were left unanswered.

Of course, Vos was not satisfied with a 63-word response. He countered to the Synod that his argument was a “detailed exegesis of many passages of Scripture and purporting to base every conclusion upon the Scriptures.” He went on to criticize the response by saying that it was “signed by one member of the committee…dealt with none of his arguments, cited no Scripture, and made no attempt to prove the relevancy of the proof texts in the…Testimony.” In 1937 Vos would boldly submit the same paper again to Synod.

That Synod appointed J.B. Willson to answer Vos, which, according to one, was “adding gasoline to already existing fire.” Willson had frequently opposed Vos on a number of issues, including temperance and Vos’s amillennialism. Willson was appointed to “answer Mr. Vos point by point as he requests.” That answer would come in 1940, six Synods after the question was first raised.

Willson Responds

The 1940 Synod received from Willson a 41-page response to J.G. Vos’s questioning of the teaching of the denomination. The response was strong. Willson spends one-third of the paper outlining the history of the RPCNA’s move from temperance to abstinence. He does this for a very specific reason, because he believed that Vos was a “novice in the history of the Covenanter Church.”

Willson also makes statements such as “his scholarship gives indications of joints in its armor.” He calls Vos’s exegesis “unnecessary and unnecessarily long.” Willson underscores that the RPCNA is “emphatically a Temperance Church” and that Vos’s arguments are ipse dixit arguments, basically claiming that, in Mr. Vos’s mind, “his position is true because he said his position is true.” He says Vos’s conclusions lead to “backwards steps” in the life of the church. Willson, after reaffirming the position against the use of alcohol, calls on the RPCNA to “not retreat.” He says, “If the position of the paper is correct, we should be ashamed of the record of the Church instead of proud of it. If the Church has condemned a practice which has the sanction of the Word of God; if the Church has made a demand of her members, which she has no right to make; if in making such a demand, she has transgressed the limits of the authority given her by the Head of the Church, then she has sinned against God, and against her members; and we ought to hang our heads in shame.”

The recommendation from Mr. Willson was that “Chapter 23 section 6…remain unchanged.” Synod agreed.

Lessons from J.G. Vos

J.G. Vos would not live to see the practice of the RPCNA change. However, the position that Vos saw as biblical, a position rejected by Synod in his day, was adopted 60 years later and is the position of the RPCNA today.

Dr. Vos provides a very important lesson for the RPCNA today. Vos, considering his minority position, said, “Being mindful of my ordination vow to follow no divisive courses from doctrine and order which the church has solemnly recognized and adopted, I have scrupulously refrained from publishing or propagating my views concerning this matter.” He was not an evangelist for his cause; he ministered faithfully in the realms in which God had given him ministry, and he refrained from teaching on that which the church held scruples different than his. He applied the weaker-brother principle in his life and ministry. Even J.B. Willson noted this and did publicly “commend the petitioner for the honorable way in which he has presented the issue to Synod.”

Being winsome and mindful of other’s scruples is important in the life of the ministry. Dr. Vos exemplified this.

Vos also was strong in his convictions. The debate between Vos and Willson, and Vos and the Synod, was going on while it was illegal to use alcohol in the United States. Prohibition reigned throughout the States. Many could have said, and may have said, that this was a fruitless discussion since alcohol consumption was not legal to begin with. But Vos did not see it as fruitless and theoretical; he saw it as a practical and an important outworking of our ethics. He said he submitted the paper “only in the interest of the truth of God and for His glory, and that the Church may be turned away from error and to the truth of all things.”

The forces of convictions and submission lived in harmony in J.G. Vos’s temperate views on temperance. He strongly held to his convictions in favor of more liberty than the RPCNA allowed, even claiming that the Synod was “pressing with increasing force upon his conscience” with their position. At the same time he was “entirely willing to submit to the judgment of the Synod on this matter” and hoped that if his position was wrong that “Synod would point out his errors that he may come to a more perfect knowledge.”

We could all learn from this debate in our church’s history. Conviction and submission are both applications of grace. J.B. Willson said it best: “Mr. Vos is a man of honor and of conscience.” May we all follow that example in our debates and our scruples as we live to the glory of God.

—Nathan Eshelman

Nathan is pastor of Los Angeles, Calif., RPC. He is a contributor to Gentle Reformation and is a member of the RPCNA Board of Education & Publication.