You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

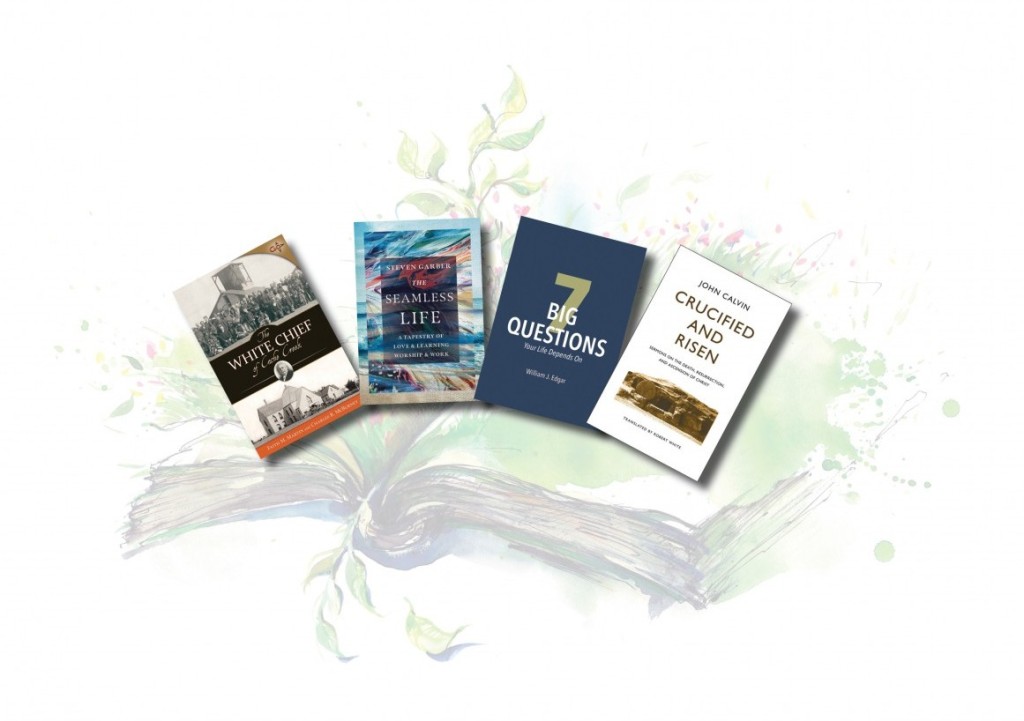

Faith Martin and Charles McBurney | Crown & Covenant Publications, 2020, 440 pp., $16 | Reviewed by Betsy Perkins

Why does our modern military have combat helicopters named for the Comanche, Apache, and Kiowa? Who were they to be thus honored? They were—especially the Comanche—proud, cruel warrior nations that fought heroically, viciously, and ultimately hopelessly while their centuries’ long way of life was crushed.

Their buffalo were gone; their chief warriors surrendered to the U.S. Army; they were confined to a territory that would all too soon be invaded by opportunistic white men of dubious morals. Their numbers rapidly dwindled due to illness and lack of their customary food sources.

How then should they live? Which new road to take? The Peyote Road, recently introduced from Mexico? Or something hard, sober, yet ultimately more eye-opening: the Jesus Road? The humbled Comanche, Apache, and Kiowa hungered for spiritual guidance.

Faith Martin and Charles McBurney’s new book, The White Chief of Cache Creek, lays out in detail the history of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America’s response to the U.S.’s conquest of the Plains Indians. “Carithers’ goal was to get the Indians safely on the Jesus Road before they had to walk the white man’s road.…[O]nce on the Jesus Road, Indians could enter white culture from a position of strength” (p. 335).

While Martin and McBurney’s book only hints at the history that preceded the arrival of missionary Work Carithers in Cache Creek, Indian Territory (later Oklahoma), the reader is well advised to keep in mind the larger picture of the United States’ conquest of the Great Plains Indians. It was notable indeed that Carithers chose to pitch his tent deep in the territory, close to the crossroads of the Comanche, Apache, and Kiowa—in stark contrast to several other Christian missions that huddled close under the walls of U.S. Army outpost Fort Sill. Carithers believed both in God’s protection and the full humanity of the Indians he was sent to preach to. He was proven right that the Comanche, along with the other tribes in the surrounding area, would respect and even appreciate those who came to help them learn how to navigate the white man’s peculiar ways.

Martin’s politically incorrect use of “Indian” helps keep the historic focus, as do rich descriptions drawn from the missionaries’ letters of their experiences with rattlesnakes, malaria, smallpox, scheming bureaucrats, measles, and murder.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Seamless Life: A Tapestry of Love & Learning, Worship & Work

Steven Garber | IVP, 2020, 128 pp., $20 | Reviewed by Lynne Gordon

Long ago, an art professor explained to me that the best artists aren’t those born with superior fine-motor skills or trained in the best techniques. The very best artists are the best “see-ers.” They see things the rest of us miss: the look of deception in someone’s posture, the purple shadow cast by a green leaf, the shape of the clouds being mimicked by the shadows on a hillside, the way the light touches a child’s inquisitive brow.

Steven Garber is that kind of artist. He has a keen sense of sight that makes you want to linger on his work and see things more clearly. His newest book marries his photography with short essays about “the seamless life.” In it, he helps the reader see, alongside him, truths of who we are, why we are here, and how we should live. He credits grace, God’s grace, for giving us the ability to see these truths. “Grace, always amazing, slowly, slowly makes its way in and through us, giving us eyes to see that a good life is one marked by the holy coherence between what we believe and how we live personally and publicly—in our worship as well as our work—where our vision of vocation threads its way through all that we think and say and do,” he writes in the heart of the book.

The book is divided into two main sections: At Work in the World and Making Sense of Our Lives. Although his use of story and references to art, music, and literature beckon you to think deeply about what you are doing and why, the small book itself is very accessible with brief chapters, a 5” x 7” frame, and only 128 pages. The Seamless Life may start a new trend in mini-sized coffee table books, because once you read it, you may want to leave it around to share with others its beauty and thoughts—perhaps precipitating those living room conversations about what Garber calls the “truest truths.” This would also be a precious gift for someone embarking on a new episode of life, young or old.

This reviewer has known the author since he was a youth leader at Covenant Fellowship (Wilkinsburg, Pa.) RP Church in the 1970s. His ability to see past what many of us do comes, in part, from his being a good listener and, in the process, not being afraid to field or wrestle with hard questions. His love for his Creator and his sense of wonder about the creation are always tangible no matter how dark or painful the question.

The only disappointment in this book is that it doesn’t do justice to Garber’s photography. Those who follow him on Facebook know that his photos capture vast landscapes, moments of marvelous light, and ranges of color and texture that, though still thoughtful and beautiful, are not fully realized in small reproductions. Maybe IVP could publish a special full-sized coffee table edition next!

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

7 Big Questions Your Life Depends On

William J. Edgar | Crown & Covenant Publications, 2020, 68 pp., $9 | Reviewed by Gordon J. Keddie

Too often, we are asked—and perhaps ask ourselves—questions like, Is the Bible inerrant? Is God a Trinity? Is Jesus divine? Should the state acknowledge Him in its constitution? Such questions are very important, but they can too easily be abstracted from the personal and experiential nature of love for the Lord, love for the truth, and love for the graces of the Christian faith. These become the cold casualties of a formal soundness on “positions,” and we fail to notice that the heart of the matter is the matter of the heart.

The perhaps unlikely big questions of this book begin with the first one asked in the Bible by the snake in the garden of Eden: “Did God really say…?” (Gen. 3:1-7). Then follows God’s question of the hiding Adam: “Where are you?” (Gen. 3:8-24); Isaac’s of Abraham: “Where is the lamb?” (Gen. 22); Jacob’s and Joseph’s: “Am I in the place of God?” (Gen. 30:1-2; 50:15-21); the astrologers looking for Jesus: “Where is the baby born to be King of the Jews?” (Matt. 2:1-12); Jesus’s: “Do you want to be healed?” (John 5:2-17); and the angel at Jesus’s empty tomb: “Why are you looking among the dead for one who is alive?” (Luke 23:50-24:11).

The author’s answers are given clearly and concisely, with supporting solid Bible exegesis illustrated with strikingly searching and often intensely personal and even humorous stories. Chapter four contains a masterly account of the story of God’s people from Joseph to Jesus’s birth, effectively rooting the questions and incidents in the unfolding of God’s covenant and the gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ. This alone is worth the price of the book. In the last chapter, the author notes how common it is for us to look for answers in the wrong places. He cites one of his students who erased his correct answers in an exam and copied his neighbor’s wrong ones!

This book is a real winner. Helpful questions for discussion are provided. Groups and classes should use it, and it is suitable for evangelism. Actually getting the facts on these seven big questions will deepen and challenge every reader’s thinking. It will profit your soul. Very warmly recommended.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Crucified and Risen

John Calvin, trans. by Robert White | Banner of Truth, 2020, 209 pp., $26 | Reviewed by Robert Keenan

I count my Calvin in four main categories: the Institutes, the sermons, the letters, and the commentaries. The sermons resonate and belie the common image of John Calvin. He preached as he served, pastorally and with an eye on his people.

Believers benefit from the recent publication Crucified and Risen: Sermons on the Death, Resurrection, and Ascension of Christ, Robert White’s translation of the great Reformer’s sermons on Matthew 26–28. It also includes as an “Annexe” Calvin’s sermon on Acts 1:9-11.

These sermons convict us as well as direct us. Prayer is neither “sorcery” nor “prattling.” Don’t faint if our prayers are not answered the first time. “Why have you forsaken me?” assumes God’s sovereign presence in our lives. It is neither despair nor whining, “Where is God? How can He leave me?” “Worthy feelings” are not enough.

I am not a student of the French language that Calvin did so much to bring into modern times, but Mr. White is. He uses vivid English to translate powerful French, for example, talking about Pilate’s boasting as part of his “shady deals” and the Roman soldiers in Matthew 28:1-5 as “rascals.”

Peter and Judas, the women on resurrection morn, why there are only two sacraments—all this and more are addressed in this fine collection of sermons. And what is the point, really? As Calvin said: “We can only await the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ if we are persuaded and convinced that he so battled the terrors of death as to free us from them and to win for us the victory.”

This is a great collection of scriptural insight that belongs on the bookshelf of any serious believer.