You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

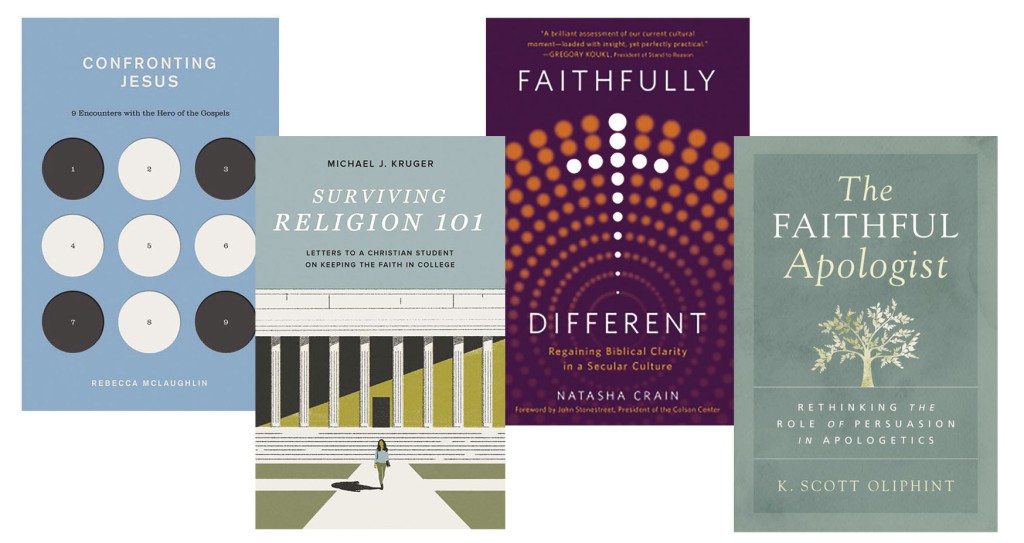

Rebecca McLaughlin | Crossway, 2022, 208 pp., $14.99 | Reviewed by Elsa Sturm

“I wrote this book partly for my own sake,” writes Rebecca McLaughlin. “Despite having been a Christian for as long as I can remember and having spent three years in seminary, I feel like I’m only in the foothills when it comes to the Gospels.” Her aim in writing this book is to “[look] straight at Jesus himself,” as His life, death, and resurrection are presented in the books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. I had greatly appreciated McLaughlin’s earlier book, Confronting Christianity, and I was intrigued by this premise. I have often felt more comfortable explaining the importance of the death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ than explaining the importance of His earthly life and ministry.

The book is divided into 9 chapters, focusing on Jesus in various roles such as son, healer, teacher, servant, and Lord. Unfortunately, the distinctions between these roles did not always seem clear; for example, the distinction McLaughlin attempts to draw between Jesus the King and Jesus the Lord is hazy. Furthermore, the subdivisions inside the chapters do not always follow a clear logical structure.

Perhaps the most frustrating piece of this book is the proliferation of references to and illustrations from pop culture. Not only does McLaughlin begin each chapter with a lengthy illustration from a book, movie, or TV show, but she also peppers these references throughout the chapter. Often, the logical flow of the text is broken by a summary of an episode of a TV show or short story. Even for someone who is familiar with most of the references she makes, this becomes difficult to read.

But the book is full of powerful references to McLaughlin’s own life and experiences. These illustrations are often especially gripping and heartbreaking. A conversation McLaughlin has with a friend shines a light on the way we often view our own sin. McLaughlin writes, “[She] wished there was a way she could have her guilt removed—‘but not by someone dying on a cross,’ she added.” McLaughlin shares stories of her own struggles with spiritual and physical sickness in an honest and humble way. This personal touch adds warmth to the evangelistic pleas throughout the book.

Overall, while some chapters such as “Jesus the Sacrifice” are effective, clear, and urgent in their message, the organization and style of the book do not lend themselves to enjoyable reading. McLaughlin writes in the introduction, “By the end [of Confronting Jesus], I hope you’ll want to read a Gospel for yourself to find out more.” I would encourage you to do just that—to go straight to the Gospels to encounter the living Word.

The Faithful Apologist: Rethinking the Role of Persuasion in Apologetics

K. Scott Oliphint | Zondervan Academic, 2022, 224 pp., $9.37 | Reviewed by Pastor Bill Chellis

K. Scott Oliphint’s The Faithful Apologist: Rethinking the Role of Persuasion in Apologetics is a defense of imaginative presuppositional apologetics. The defense is timely. When I was a young pastor, Reformed apologetics meant the presuppositional apologetics of Cornelius Van Til. All the cool kids were Van Tillian. Twenty years later, a renaissance of Reformed scholastic theology has made the classical apologetics of Thomas Aquinas and his Protestant children all the rage. One is tempted to say that we are all Thomists now. But there is Thomism, and then there is Thomism. That is to say, there is a delight in the rational, and then there is rationalism. In our apologetics, Reformed Presbyterians put our Augustinian horses before our Thomist carts, always seeking to build our reason upon the foundation of faith rather than our faith on the foundation of reason.

And that brings us back to Oliphint’s book, The Faithful Apologist: Rethinking the Role of Persuasion in Apologetics. This book is a very readable and accessible introduction to the presuppositional approach to apologetics. Oliphint is the right man for the job, serving as professor of apologetics and systematic theology at Westminster Theological Seminary. From his perch in Van Til’s seat, Oliphint has written several books and articles, some defending presuppositional apologetics and some criticizing Aquinas and his classical apologetic method. The former works are far more helpful than the latter. His most recent work, The Faithful Apologist, fits into the former and helpful category. With a length of roughly 200 pages, Oliphint writes in a conversational, readable style. The book reminds readers that while the triune God is the great apologist and ultimate persuader, we must be as harmless as doves and crafty as serpents. Being persuasive matters.

In the book’s first part, Oliphint seeks to make Augustinian apologetics great again by reminding the reader that unbelievers are saved by irresistible grace and not irresistible arguments. Persuasion belongs to the Lord, but that is no excuse for bad arguments. In the book’s second half, successive chapters explain the parts and principles of persuasion under the headings of ethos, pathos, and logos. The sum is that the faithful apologist must be a credible voice (ethos) who understands the struggles of his audience (pathos) so that by artful use of language, we might offer persuasive arguments that speak to both the heart and mind of the unbeliever (logos).

According to Pascal, “the heart has its reasons of which reason knows not.” No argument is so intellectually profound that it will convert every unbeliever. We could walk by sight rather than faith if such an argument existed. Instead, faithful apologetics is art, not science. Good arguments require a faithful apologist to speak to hearts and minds—not blunt jabs but imaginative strokes. The art of persuasion requires both a faithful God and a faithful apologist to be effective.

Faithfully Different: Regaining Biblical Clarity in a Secular Culture

Natasha Crain | Harvest House Publishers, 2022, 268 pp., $17.99 | Reviewed by Meg Spear

Faithfully Different by author and apologist Natasha Crain provides an insightful analysis of our culture and sounds a clarion call for Christians to live biblically in the midst of the strident secularism that surrounds us.

Crain postulates these four guiding principles of current culture: “Feelings are the ultimate guide, happiness is the ultimate goal, judging is the ultimate sin, and God is the ultimate guess.”

In the revelatory first section of the book, she clearly illustrates that a true Christian worldview is a minority position in the United States. In fact, it is a minority among active churchgoers! A scant 17 percent of Americans who consider their faith important and who attend church regularly believe in absolute moral truth, biblical inerrancy, Satan, salvation by faith, Jesus’ sinless life, and the sovereignty of the creator God.

Crain states that a secular worldview can even become compelling for Christians because of its prominence in our culture and apparent relevance to our lives, appealing directly to the autonomous desires of our sinful nature.

The second section of the book explores what it means to believe faithfully in the face of naturalism, individualism, and public deconversions. Crain gives helpful arguments for the existence of God, embedded in the knowledge that people respond differently to evidence for a variety of reasons.

She highlights the fact that biblical Christians often face intense pressure from progressive Christians, who are inclined toward an “a la carte” version of Christianity, picking and choosing what parts of Scripture to adopt. She also includes a brief section about how to handle our own doubts when they arise.

The third section of the book explores what means to think faithfully. As opposed to the early church, which needed apologetics to introduce a biblical worldview to the dominant culture, Crain claims that “today’s church needs a strong apologetic foundation to reclaim the borrowed parts of its worldview from a dominant culture.”

Drawing on her experience in marketing, she shows how cleverly new ideas and standards of morality are developed within our culture as unsuspecting people are unconsciously funneled through progressive psychological stages of redefining words (“equality”), normalization of previously offensive behaviors, and finally the celebration of these behaviors.

Despite revealing so many discouraging things about our culture, the author does not leave us without hope. In fact, the final section of the book is a call to live faithfully, knowing that in Christ we have the ultimate victory as we revitalize the call to biblical justice, recommit ourselves to speaking truth, and reshape our hearts for sharing the gospel.

Crain encourages us that our faithfully different lives are important, and that our words are important, as we steward the best news of all, bearing fruit for Christ’s kingdom in the pressure cooker of life.

Surviving Religion 101

Michael J. Kruger | Crossway, 2021, 272 pp., $16.99 | Reviewed by Chris Eddy

Among apologetic works geared toward encouraging young people in the Christian faith, it would be difficult to find a better book than Surviving Religion 101. Michael J. Kruger serves as president and professor at the Charlotte, N.C., campus of Reformed Theological Seminary. Written as a series of letters to the author’s college-age daughter, this work seeks to address some of the most common objections to Christianity—including inerrancy of Scripture, belief in miracles, existence of hell, and biblical morality—and to provide winsome arguments for orthodox Christian faith.

Despite the social, moral, and intellectual atmosphere on college campuses that pressures young people to leave behind their faith, Kruger labors in this helpful book to empower Christian students to “keep their faith without sacrificing their intellectual integrity” and to “realize that belief in Christianity is not just intellectually defensible but also intellectually satisfying at the deepest of levels.”

The book’s format and writing style make it highly approachable, with each chapter devoted to one of 13 common objections to faith that believers typically face. Although the truths addressed in the book are theologically and philosophically profound, Kruger explains them in ways that should be understandable to most high school and college students. Each chapter takes about 15–20 minutes to read, making the book well-suited to personal devotions or a group discussion in a Sunday school setting.

Kruger recounts that during his Christian upbringing, he received sound instruction on the necessity of personal conversion and personal piety. As important and helpful as those two avenues of Christian education are, he says that his theological training went no further: “There was very limited instruction on the Christian worldview—what we believe and why we believe it—and virtually no instruction on how to respond to non-Christian thinking.”

He additionally advocates, “Christians need to think more seriously about how to prepare the next generation of believers to handle the intellectual challenges of the university environment (and beyond). We need to do more than prepare them morally and practically; we need to train their minds to engage effectively with an unbelieving world.” His attempt to do just that in this new book is well worth reading and discussing with young people in your family or congregation.

And that brings us back to Oliphint’s book, The Faithful Apologist: Rethinking the Role of Persuasion in Apologetics. This book is a very readable and accessible introduction to the presuppositional approach to apologetics. Oliphint is the right man for the job, serving as professor of apologetics and systematic theology at Westminster Theological Seminary. From his perch in Van Til’s seat, Oliphint has written several books and articles, some defending presuppositional apologetics and some criticizing Aquinas and his classical apologetic method. The former works are far more helpful than the latter. His most recent work, The Faithful Apologist, fits into the former and helpful category. With a length of roughly 200 pages, Oliphint writes in a conversational, readable style. The book reminds readers that while the triune God is the great apologist and ultimate persuader, we must be as harmless as doves and crafty as serpents. Being persuasive matters.

In the book’s first part, Oliphint seeks to make Augustinian apologetics great again by reminding the reader that unbelievers are saved by irresistible grace and not irresistible arguments. Persuasion belongs to the Lord, but that is no excuse for bad arguments. In the book’s second half, successive chapters explain the parts and principles of persuasion under the headings of ethos, pathos, and logos. The sum is that the faithful apologist must be a credible voice (ethos) who understands the struggles of his audience (pathos) so that by artful use of language, we might offer persuasive arguments that speak to both the heart and mind of the unbeliever (logos).

According to Pascal, “the heart has its reasons of which reason knows not.” No argument is so intellectually profound that it will convert every unbeliever. We could walk by sight rather than faith if such an argument existed. Instead, faithful apologetics is art, not science. Good arguments require a faithful apologist to speak to hearts and minds—not blunt jabs but imaginative strokes. The art of persuasion requires both a faithful God and a faithful apologist to be effective.