You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

_________________________________________________

What is Reformed theology?

Reformed theology speaks of a tradition of Christendom that got its shape in the 16th century through the work of John Calvin. It has been essentially that shape ever since Calvin, but it wasn’t really new with Calvin. The essence of it is a God-centered way of thinking about God which highlights His Lordship over His world and particularly His Lordship in the matter of saving grace. So divine sovereignty is rightly pinpointed as a Reformed distinctive.

We talk alot about applying our faith to our everyday Iife and work. What are some practical ways for Reformed people to apply this Reformed theology to their everyday life?

Reformed folk, those who know themselves to have been saved by God’s grace, have no anxiety about their eternal destiny as they know God finishes the work of grace that He starts. They know too that the Bible is His Word and it is a reliable guide to His will.

On more basic issues, issues of life which relate in any way at all to fellowship with Him, they take their Bibles in their hands, therefore, and from what’s written they seek to discern the will of their sovereign God and obey it. There are, of course, distinctives in the Reformed understanding of what Christian obedience means, but the first thing I want to say about it is that Reformed Christians belong in the evangelical family. By that I mean the larger community of those who accept that what happened in the 16th century Reformation was a putting straight of disorder and disfigurement of Christianity rather than a further disfigurement; which is of course what Roman Catholics would say, and what certain modern protestants are trying to say now. But that wouldn’t be Reformed.

Within this bigger evangelical family, the distinctive thing about a Reformed Christian is likely to be this: Starting with God as the center of his thinking, he knows that the glory of God in His world is the end of all things; and never forgets that God made the world and all that is in it, including ourselves, so that His name might be honored and glorified. That is so that there might be, at the end of the day, rational creatures worshipping Him for all the goodness and wisdom and other admirable qualities that He has shown in the making and governing of His world.

The Reformed Christian is actually obliged to think of his obedience in terms of a total view of God’s will in His world. In other words, though the Reformed Christian I hope will be a person of strong individual piety whose personal walk with God is a matter of great concern to him or her, that same Reformed Christian will not limit his concern to matters of personal piety but will be, on a larger horizon, trying to see God’s will for his world, praying for that and working for that. So the Reformed Christian will be trying to do a number of things at the same time: to keep his or her personal life free from anything that the Bible calls sin, and to fill his or her personal life with a positive obedience to all God’s specific commandments as focused in Christ’s two great commandments—to love God and to love your neighbor as yourself. The Reformed Christian will be taking very seriously the relational units in which God has set him—his own family to start with, the local congregation of which he or she is part and beyond that, the larger national and socio-economic units of which he or she is a part as well.

And the Reformed Christian will be looking out to what is going on around him. His thoughts and prayers will have to do with what is going on in the world. Whereas in the evangelical spectrum, you’ve got a graded transition from people who have this broad Reformed view to a people who really think about nothing and pray about nothing except their own personal walk and maybe their own family and specific interests of the church and those narrow concerns. The Reformed Christian will have a conscience about keeping his horizons wide and he will feel that other evangelicals who don’t have a horizon so wide as himself are missing something of God’s calling and therefore of their own responsibility as God’s people in this world.

And in his testimony to the world, the Reformed Christian will be saying a good deal about this just as he will be saying a good deal about what’s involved in the kind of piety he practices which takes more seriously perhaps than any other tradition in Christendom the depth of moral and spiritual twistedness which results from human sin.

Reformed people have a more radical view of sin than others and, therefore, a deeper view of what the work of grace is as the Lord, by His Spirit reaches down into the depths of our being in order to straighten out what’s crooked.

So those are the two distinctives I expect to find in a Reformed Christian as distinct from others. He has a broader view and a broader range of concern about the glory of God in God’s world and he has a deeper view than others do about the complexity of the work of grace and sanctification. Reformed Christians often seem to others, who don’t quite realize what is going on, to be “preaching up sin,” while what Reformed Christians are actually doing is trying to stay realistic about their diagnosis of the depth of sin and recognize that the work of grace which touches every part of our life hasn’t fully perfected anything in our life as yet.

Why do you think it is so hard for people to hold that piety and the broader horizons together in their world and life view? Often people will choose to go one way or another and it seems that they must be together.

Let me say first that because fallen creatures like ourselves are mentally lazy, we are inclined always to find it difficult to grasp big pictures. It is the easiest thing in the world to become one-sided about anything. That is the first reason why some stress one and forget the other. Some stress the other and forget the one. Imbalance, and I think, narrowness, preoccupation, inability to wrap our lives around a big picture is just the legacy of sin.

I think there is a second reason also. It does take effort, mental and spiritual effort, to grasp big pictures just because they are big pictures. And some folk find it hard to appreciate that we need to look to God to enable us to have a large enough view. I suppose the second reason is just an extension of the first. I say one-sidedness comes so easy for all of us.

Do you have any favorite models of people, either in our century or past centuries, who seem to have held those together?

Yes, there certainly are people with whom I have kept company through their writings who have been able to do it. As far as I am concerned they are models, they are inspirations to me—people like Augustine, Calvin, the Puritan John Owen, and Abraham Kuyper. I could add to that list but those are the people who come immediately to mind.

Then of course, there are folk who are called against the background of this world view that I have just tried to sketch out. They are called actually to major in one area rather than another. So that you would think from their written testimony, books they produce, sermons they preach, and so on, that they are more one-sided than in fact they were. You never really know what a person is concerned about unless you know what he prays about and only the Lord really knows that. For example, people like John Whitefield, Charles Spurgeon, who had a tremendous ministry in England during the last century, or Martin Lloyd-Jones in our own day knew that they were called to be preachers and they invested the whole of themselves in their preaching ministry. Their preaching ministry was evangelistic and pastoral in very basic ways and they have not gone on record as saying anything of particular profundity about larger cultural and sociopolitical and economic questions. But they were whole men, giants spiritually before the Lord, and I am sure that in their prayers and in their hearts there was a wider concern although they knew their own calling and stuck to it. They were pastoral evangelists and pastoral preachers and they didn’t go beyond that.

How would you describe the state of the Reformed church today?

First let me say what I take you to be talking about and certainly what I talk about when we use this phrase, “Reformed church.” I am thinking of a number of conservative Presbyterian denominations to start with, and in addition I think of what you might call the broad Calvinistic constituency within other larger groups which are not uniformly committed to that point of view. I am a Reformed Anglican. There are quite a number of us around, but we are nothing like a majority anywhere in the Anglican community. Similarly, in the Baptist world, there are Reformed people, quite strong groups in some of the larger churches. And so I am talking about all those people in any constituency of course, and the publishers and the literature which hold them together.

Generalizing now about the Reformed world, the first thing I want to say is that in my lifetime, I think I have seen a very significant quickening at the level of Reformed piety through the efforts of bodies like The Banner of Truth Trust with their reprints of the classics on Christian piety from the past, and also through the pastoral preaching of some of the Reformed preachers and teachers whom God has given to us in these days. I think particularly of people like Martin Lloyd-Jones in England and Jim Boice who is in the heyday of his ministry here in the States. I think there has been a real measure of spiritual quickening within the Reformed people. I first came into the Reformed world, not so much the result of the proselytizing or the pull of any living Reformed people as it was the result of what God was doing to me through my Bible study plus the discovery of some of the Reformed giants in the realm of piety, particularly J. C. Ryle and John Owen.

Then I discovered that there were such people around today, but my impression of them when I first came to know them was that they were really rather stuck in the mud, deeply anchored in that vision and not really very lively in their propagating of it in our time. And I think I have seen over 30 years a lot of quickening.

Now I see churches, where the Reformed faith is the standard of preaching and teaching, in a much livelier state than they were 30 years ago. That is a comment on Britain and 20 years ago it would be a comment on things this side of the Atlantic as well.

Piety is more Biblical, godliness goes deeper I think, testimony is stronger, and the Reformed folk are making more noise in the evangelical world. Noise, I mean to the effect that the really ripe, mature, scripturally structured Christian view is that which you find in the Reformed world rather than anywhere else. It is not being said in a sectarian way, but that is what is being said by Banner of Truth people in their reprints and there are other reprint bodies and some Reformed presses that are turning out new works. I think that the point is being taken because Biblically it proves to be true when people examine it. There has been a leavening of Reformed thought and Reformed devotion throughout the whole evangelical world, in some places not very strong, but in some interdenominational circles where there really wasn’t very much of this at all 30 years back, there is quite a lot of it now. If you look, for instance, through the world of lntervarsity and the world of Campus Crusade, you will come across people who will quietly say that their theology is Reformed and their inspiration and piety comes from Reformed sources. In the days of my youth there was really none of this Reformed rhetoric, but there’s a great deal of it now.

I have also seen a quickening of concern for the Reformed world view and the acceptance by Christians of their proper responsibility in the fields of general culture, socio-economic fields, political concern, areas of that kind. All of creation for God, that kind of concern. And that has been an expression that just wasn’t there among Reformed people 30 years back.

So in all these ways, I think the Reformed cause is stronger now than it was in the 50’s. But the other side of the story is that there is still a great deal of ground to be possessed. I would like to see the Reformed influence much, much stronger than it is. When I first began to take notice, it was rather apparent to me that Reformed people were very much turned in on themselves—“We are the people. We are the Christians who are truly pure in faith and practice.” To quote Robbie Burns—“Here’s to us and who is like us,” that kind of attitude you know. There is still a certain amount of that, less than there was, but still more than I would like to see. Call it insularity or what you will, it is not a lovely thing to see.

I am not, of course, a prophet, nor a prophet’s son, but if you want me to look into the crystal ball, I think that the Reformed faith is evidently alive and well and can be expected to make further progress along these lines over the next 20 or 30 years. I say that partly because the seminaries which have a Reformed commitment are in such good shape and have so many students. Those who are going through the seminaries now are going to be church leaders for the next 30 or 40 years and what they bring out of seminary with them today is what they are going to be teaching and propagating during those 40 years of ministry. There are a number of seminaries today with a Reformed commitment. The R.P. Seminary is one of them. You have 75 students and that is good. There are other seminaries, much larger units which have much larger student bodies and that is good, too. Without looking any further, one can say with confidence that this is going to make a difference in the quality and thrust of teaching given in the evangelical sector of the Christian world in the next half century or so.

You have talked about the need for revival in the church. Tell us what you see to be the necessary prerequisites for revival in the Reformed church.

Well, I’m going to talk about this in the presentation this morning, so I am deliberately not going to say very much about it now. But, I am going to warn people not be tripped up by what I call the antiquarian and romantic fallacies. The antiquarian fallacy is the assumption that God’s work of quickening His church today is going to be a carbon copy of His work of quickening the church in the nineteenth, eighteenth, seventeenth, sixteenth or any other century to which you go back for revival movements of yesterday. And the romantic fallacy is to suppose that any quickening of the churches in our day will mean an end of all their internal problems. It does mean a change to internal problems. You have the problems of disorderly life when revival comes, the sort of problems that Paul was trying to deal with in 1 Corinthians, in place of the problems of complacent spiritual death, the problems to which the Lord is addressing himself in the letter to the church of Laodicea in Revelation 3.

The essence of God’s work of quickening is that the awareness of God’s reality is intensified, the sense of sin is deepened so that the people of God become more humble, and their sense of the need of Christ’s cleansing blood becomes more acute. Repentance goes deeper; there is more of a conscience among God’s people about not compromising with sin. God in His sovereignty speeds up His work so that Christians mature more rapidly and churches become more potent witnessing bodies just because there is more vital energy for Christian testimony amongst the people of the church. There is an evangelistic overflow and the world feels the impact and folk come in because they know that the Lord is with these people. I think that it is a given pattern in the Scriptures.

I think that each work of spiritual revival and quickening has its own individual characteristics derived from particular pressures and problems of each age in just the same way that God’s work of regeneration in the life of an individual has its own particular characteristics deriving from that individual’s temperament and personal history. Nonetheless, in essence, the work of revival, quickening of the church, is characteristic in itself and standard. The spiritual heart of it is always the same in just the same way that God’s work of regenerating an individual is characteristic and standard in the change. The basic change of nature is always the same. That is the whole of my story, so to speak, in asking how I view the matter.

The overflow will not simply be evangelistic if God quickens us. The overflow will be to every field of life where Christians are called to bear a testimony, to live in a certain way and exercise an influence for good. And what that will mean in our day depends on where we see the particular areas where vigorous Christian influence is most needed. I won’t pretend that Reformed Christians are agreed fully on what those areas are; I have my own thoughts, but it is very obvious that Christian influence is needed. There are a whole series of moral questions about community life and community responsibility where standards are slipping. The abortion questions, the euthanasia questions, solidarity of the family questions, stability of marriage questions, and the morality of the industrial world where you are asked to sell your soul to the firm otherwise you have no future with the firm, all that kind of thing is dishonoring to God, and these are areas where God’s people need to be making much more impact with force and vigor.

You don’t just need Reformed people actually. God is like that. He doesn’t always send his richest blessing and spiritual revival on the soundest and most orthodox souls. Blessing actually comes to those who seek Him most earnestly. You can go back to the eighteenth century, the Great Awakening, the ministry of George Whitefield, are marvelous examples of how God blesses. Revival dimensions consist of Reformed testimony, for sure, but the same blessing was poured out on Wesley and his Methodists and as you know they were professedly Arminians and professedly apart from the Calvinists over the understanding of the doctrine of grace. But God didn’t withhold His blessing.

You have talked about the element of renewal of worship as being central to renewal of the church at large. Two questions, then: What elements in Reformed worship are strong and healthy and what elements in Reformed worship are weak and unhealthy? Could you bring those questions together?

Reformed people have turned their back, a little too thoroughly I think, on the liturgical principle. We can use the Lord’s Prayer in our worship; we have sung Psalms; but apart from the Anglicans, who are at this point out of step with the rest of the Reformed world, we have not allowed ourselves to use the liturgical forms at all. That I think has been a source of greater loss than it has gain. We have only extemporaneous forms of prayer in our heritage. We have proved vulnerable to the desire to make worship of God edifying for people. Much too much of what goes on in our standard worship services is entertainment and encouragement of people rather than adoration of the Lord. On this point I think that the Charismatics have alot to teach us because they have said in their godly simplicity, we are gathering together to worship and simply to praise the Lord. There isn’t a need for a horizontal thrust in the worship, whereby its hidden agenda is to encourage and edify us. We just look straight at the Lord and praise Him and thank Him for all that He is and we can spend an hour at a time doing it if we live that way. It is a very proper thing for us to be doing. You don’t really get that emphasis in the “hymn sandwich” of Reformed worship as we know it today. There seems to be an understanding of the importance of preaching and a willingness to preach and hear mansize sermons (You do know what I mean by man-size sermons—half an hour to three quarters of an hour) in the Reformed world and that is good. But whether those sermons point to God with sufficient clarity as distinct from brooding on life in a way that obscures God is another question. Whether those sermons embody enough applicatory stuff in searching the conscience of the hearers is another question. At least Reformed people are prepared to accept man-size expositions, not 20 minutes maximum effort which is all you get in some congregations where worship can’t go on more than 60 minutes because you have to be out of church by 12 midday or else there is a row.

When it comes to celebrating God, when it comes to sustained intercession by his people around His Word, I think our worship is pretty shallow for the most part and needs quickening at that point. These are things that immediately occur to me.

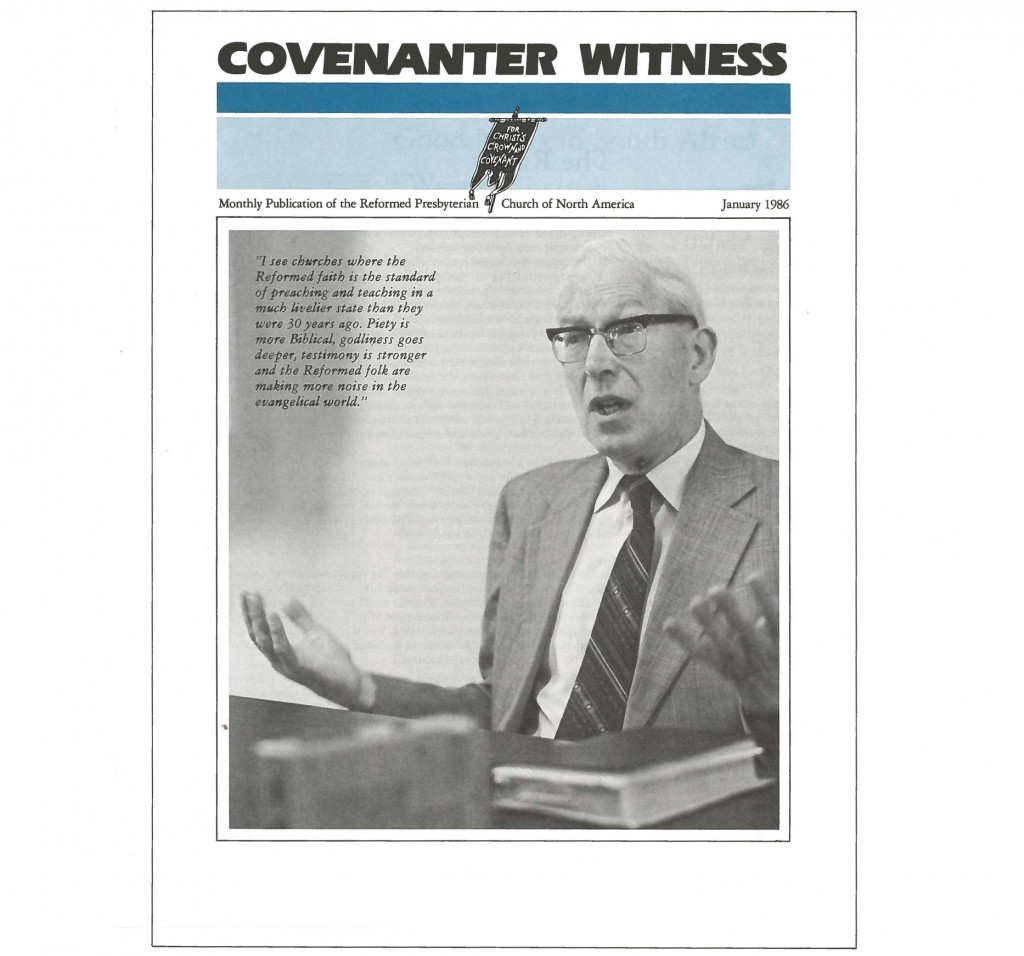

Noted conservative theologian and author, Dr. J. I. Packer serves on the faculty of Regent College, Vancouver, B.C. He was guest lecturer last Fall at the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary, Pittsburgh, Pa.