You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

You might be familiar with Christ (Floyd, N.Y.) RPC, but did you know it’s the third RP congregation in its area? The first RP settlers arrived in the 1830s, soon after the RPCNA divided into Old Light and New Light sides, and they adhered to the Old side.

Congregations were organized in New Hartford and Utica in 1837, and, in late 1840, Francis Gailey came to preach for them. But, by mid-1841, the congregations were gone. Gailey had previously formed a “Safety League” to preserve true Reformed Presbyterianism from the fake ministers in the rest of the church, and the congregations followed him readily. But who was Gailey? What was the Safety League?

Francis Gailey was born in Ireland in 1802, and as a teenager he accompanied his parents to New York. After studying under future RP Seminary professor J.R. Willson, he was licensed by the Northern Presbytery in 1830 and began preaching throughout the Southern Presbytery (now Atlantic Presbytery), especially in Baltimore, Md. Although he wasn’t yet ordained, he started acting as if he were; and when he received two calls in 1834 the presbytery would not ordain him.

Hudson River steamboat repairs forced Gailey to wait in New York City until after the presbytery meeting in Albany, N.Y. While waiting, he coincidentally met with some friends from the churches there, and, upon reaching Albany, he learned that the presbytery had “almost instantly murdered” the calls that had been made on him. He interpreted these events as God specially commending him and condemning the cabal who had opposed him in the presbytery.

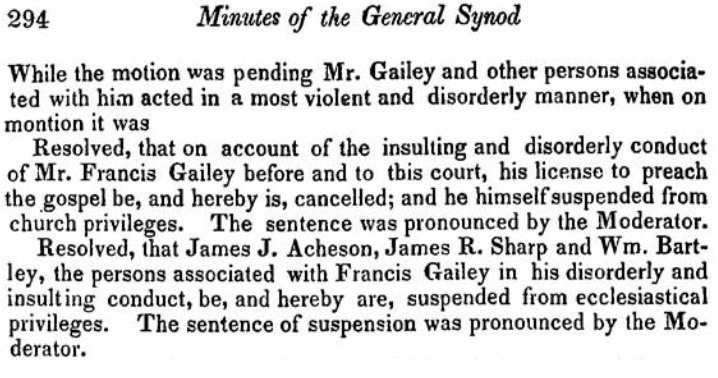

From this point on, Gailey began attacking ministers in his presbytery and elsewhere in the church. They were power hungry, he concluded. After the 1833 division had freed them from dealing with New Light opponents, “they became fierce and outrageous against the most faithful individuals in their communion.” He continued these attacks for four years, becoming so odious that, in 1838, Synod handled the case directly. He was un-licensed and suspended from membership.

Instead of obeying Synod, Gailey started to divide the church. In 1839, he began a new magazine, the American Reformed Covenanter, to publish his views, and he organized his followers as the Safety League. He began seeking converts in Baltimore, Md.; Ballibay, Pa.; New Hartford, Utica, Kortright, Bovina, and Walton, N.Y.; and Brush Creek (Locust Grove, Ohio). Eight elders from these congregations followed him and left the church, bringing many other members with them.

While Gailey attracted many followers, his attitude alienated him from all RP ministers, and none followed him, even the few he still respected. Eventually, he and his followers despaired: with no ministers, they couldn’t have the sacraments or perpetuate their church. In Scotland, RPs had endured for decades with no ministers, but apparently Gailey couldn’t accept this possibility. What could be done?

Eventually, he concluded that the RPCNA was so corrupt that extreme measures were justified. The true church needed a ministry, so Gailey, as God’s appointed agent, could declare himself a minister without ordination! And a false church’s sacraments couldn’t be valid, so he rebaptized all his followers. However, this was so extreme that followers soon started returning to the RPCNA. Some members remained—he continued publishing his magazine until 1854—but they too eventually abandoned him. Gailey died in New York City in 1872, alone.

What did Gailey teach? The early volumes of his magazine highlight some of those teachings. At the time, the RPCNA was undergoing a controversy over the diaconate. Some churches had consistories, in which deacons and elders made decisions together (similar to some NAPARC denominations today). Others had deacons manage church finances and property, as we do today. Yet others opposed both these practices. Gailey lay firmly on the anti-deacon side, concluding that deacons should not manage church finances or do anything else, except caring for the poor.

Perhaps most significantly, Gailey opposed any kind of participation with non-RPs in voluntary organizations. The church had opposed slavery for a generation, and a few ministers had begun joining antislavery societies. However, because these societies promoted political activity, Gailey concluded that their members were enemies of the church’s position. In fact, he saw their willingness to operate under the U.S. Constitution as allying them with the slavery system that they claimed to oppose. He even attacked one prominent RP minister, James Chrystie of New York City, for allegedly enriching himself with slave labor.

Opposition to voluntary organizations became a hallmark of the “Steelites,” other dissidents who left the RPCNA around 1840 under the leadership of David Steele. The two movements appealed to the same ultra-conservative constituency; but because Gailey was alone and so radical, his group died out quickly. Conversely, the two Steelite ministers built several congregations, one of which endured until the late 1990s.