You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

The Bible Could Mean So Much More to You

As a culture, we no longer believe that we can know truth—big truth, meaning-of-life kind of truth, the kind of truth that might address and even appease our deepest anxieties, the kind of truth the Bible claims to be.

Instead, we’ve come to believe that we cannot know reality as it actually is, that there is no absolute truth. Or, if absolute truth does exist, we cannot know it with any real confidence—practically the same thing. But do you notice something a bit off about these beliefs?

These claims self-destruct as soon as they’re made. The reality is that we cannot know reality as it is. We’re absolutely sure that there is no absolute truth. Or, the more modest version: We’re very confident that any absolute truth out there cannot be known with any real confidence. Each of these statements violates the principle it’s meant to express before the sentence stops. Shouldn’t we be suspicious of ideas that can’t even be stated without imploding?1

Pointing out these inconsistencies is nothing new.2 The stunning thing is that we don’t care about them. Somehow, as children grow up in this culture, they come to accept such self-destructing statements as, well, absolute truth. The suicidal inconsistency of these ideas doesn’t seem to bother us at all.

We never accept inconsistencies when it comes to the things we care about. If someone gives us 10 dollars but tells us he’s given us 100, we don’t shrug and say: “Well, who’s to say what’s true anyway?” We call shenanigans on it and demand proper payment. But when someone slips us the idea that we cannot know truth and calls it truth, and we sincerely believe it, that’s evidence that something is missing within us—something that would stop that philosophical transaction and at the very least say, “Wait. What?!” When we don’t even pause at that kind of proposition, it’s evidence that something’s been stolen from us.

This robbery has reached into all of our hearts. Even if you affirm that the Bible is knowable, absolute truth, don’t you find that there’s something missing in your desire to know it?

Be honest: Are you ever bored with the Bible? Or at least, does reading it ever feel like a chore? How often do you pick it up, and how quickly do you put it down? It’s one thing to avoid the Bible because we have a hard time understanding it. That’s natural, and that’s where this book seeks to help. But if we’re Christians, something major must be missing from our hearts if we are at all disinterested in the word of our Lord.

If we really, truly believed that the Bible is the word of God, and that through it we can actually get to know God, then how could we ever regard the Bible with anything less than the utmost awe and eagerness to explore? But that awe and eagerness are missing from the hearts of so many Christians today, and that’s a crime. How did the thieves get away with it? Suffice it to say for now, the thieves had a lot of help…from Christians.

“I Can Do It Myself, Dad!”

Sometimes Christians make the best criminals, or the best unwitting accomplices to a crime. About five centuries ago, in what may have been the Christian church’s “Doh!” moment of the millennium,3 a Christian mathematician in France tried to prove God’s existence beyond the shadow of a doubt. That effort is questionable to begin with, but he made matters so much worse by trying to prove the existence of the God of the Bible without seeking any help from the Bible. He thought that the Bible would be just fine with that.

René Descartes (1596–1650) understood the Bible to say that human reason, by itself, could teach us everything we needed to know about God.4 Kind of makes you wonder why we would need the Bible then, right? Hold that thought.

Descartes thought that, by the process of proper reasoning, he could discover the most basic, fundamental, knowable, indubitable truth. Once he found that rock-solid knowledge, that truth buried deep beyond the reach of any reasonable doubt, he could use the process of proper reasoning to build upon it other truths that we could also know with absolute certainty, including the knowledge of God’s existence. Like a toddler who wants to impress his dad by trying to ride a bike on his own, Descartes was as sincerely desirous of honoring God by his unaided effort to prove God’s existence as he was confident that he could pull it off. And oh, was he confident. And oh, did he crash.

Descartes was sure that, as a result of his writings, and with a little editorial advice from a world-famous theology faculty (along with their money and endorsement), “there will be no one left in the world who will dare to call into doubt…the existence of God.”5 The effort was a spectacular fail. Likely suspecting as much, that faculty never endorsed it.

Descartes went wrong at the very beginning. He decided that the most basic truth of which he could be absolutely sure was that he was thinking. “I think, therefore I am.” In other words, I know I exist because I recognize that I’m thinking. Descartes thought that was the bedrock for building human knowledge. But wouldn’t belief in the God who created him be even more basic than that? After all, how did “I” get here to begin with? And how did “I” get the capacity to recognize that “I” is thinking? And without any help from outside “I,” how can “I” be sure that “I” is thinking correctly? And why does anyone like philosophy?!

By trying to ground true knowledge in the thinking self and by placing supreme confidence in human reason rather than God’s revelation of himself in Scripture, Descartes inadvertently treated the Bible like the bench player I was on my high school basketball team. I was necessary to fill the roster, but utterly unnecessary to win the games. I barely counted as eye candy.

Descartes made supreme confidence in human reason intellectually fashionable. His work resulted in the rise of Rationalism, which exalts human reason as the infallible guide to absolute truth and the arbiter of what counts as absolutely true. Reason, not God’s revealing himself and his will in Scripture, would rule the new world to come. Major advances in science, coupled with the church’s apparent disdain for them, seemed to confirm that hypothesis.

The nail in the coffin of Christian confidence in Scripture may have come when people began to distrust the Bible even as God’s guide to a good moral life. Europeans in the rising 18th Century were weary from so many wars; in many of them, all sides claimed scriptural support for their slaughter of other people. Maybe the Bible was no good at all, at least as a direct word from God.

The separation from Scripture that Descartes accidentally spurred wasn’t supposed to last. He merely meant to prove, especially to non-Christians, the reasonableness of the faith that Scripture details. But like so many separations meant to strengthen a relationship, it ended in divorce.…

The separation was seismic, and it set the stage for thieves to swoop in later and snatch from people’s hearts any rising hope of a personal encounter with a personal God. Such encounters were declared absolutely impossible. This declaration of independence from God shook up the Western world; we feel the aftershocks in those suicidally inconsistent, soul-crushing ideas embraced as absolute truth today.

The Bible Takes God Seriously: Do Christians?

The Bible is written to and for people who’ve never seen Jesus, telling us that we can be so close to him that he becomes our very life (John 20:31, Col. 3). The Apostle6 Peter wrote to Christians who had never seen Jesus but who truly believed in him; they were filled with “joy inexpressible and full of glory” (1 Pet. 1). But as we look around us at Christians in our culture—and within us if we are Christians—don’t we find, by and large, a relatively “meh” attitude toward the Almighty?

Isn’t it common for Christians to talk about Jesus with far less interest than we show for our favorite team, music, or food? If the objects of our truest affections all met in one event—if we could eat our favorite food at the big game with our favorite band playing the postgame concert—wouldn’t that be heaven? But then we’re brought down to earth by remembering that we have to get up early the next morning for church, just to worship some resurrected God-man. Borrringgg. “Oh look, fly ball!…Wait, what?! HOME RUN! Game over! Bring out the band! Pass the grub! I am so sleeping in tomorrow!”

Don’t get me wrong. I love sports, Boston-based sports especially. These are God’s blessings. Remember the 2004 ALCS, Yankees fans? Heh heh. And I love music and food, too. Alternative rock! Chowda! These are ways to experience God’s goodness, and we should praise him for them. But why is it when we’re called to turn our attention away from the gifts to pay more attention to the giver, we so easily lose focus and interest?

The statement that James cites, “God is one,” comes from the great prophet Moses in the Old Testament book Deuteronomy (6:4)7 and is followed immediately by a command to respond to God in the only manner worthy of him, a command that Jesus calls the first and greatest commandment (Matt. 22:37): “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength.” When it comes to loving God, it’s all-in. So isn’t something off if worshipers of the Lord of heaven and earth can’t wait to leave the worship service on Sunday to sing and dance before the gods of the gridiron? Who, or what, is truly our first love?

You might say: “I’m not bored with God; I’m bored with church.” Fair enough. But what if there was just the tiniest chance that, in the midst of some truly blameworthy boringness at church enacted in Jesus’s name, we might, if only for a few fleeting moments in worship, actually interact personally with the true and living God? Shouldn’t that mere possibility make us willing to camp out the night before like we would for a concert or film we can’t wait to see?8 Shouldn’t we be willing to miss the big game or scrap the lunch plans if they conflict with the public worship of the God we love? If not, then don’t we Bible-affirming believers have to admit that, as it can be in a troubled marriage, we’ve become bored with our first love?

But think of that for a second: bored with God. How can that be? There’s a sense in which it can’t be.

Up in Flames

The idea of God is incendiary. In the Bible’s book of Proverbs, the author asks, “Can a man carry fire next to his chest and his clothes not be burned?” (6:27). Even a few seconds of serious thought that a being worthy of the title “GOD” might exist should spark something inside of us. So shouldn’t the belief that God does exist be a blaze in the depths of our being?9

For the biblical prophets, the fact that God exists and has spoken was sometimes too much to bear. But torturously, it was too compelling not to share.10 Jeremiah is called the Weeping Prophet. He foresaw and lived to see awful judgment upon his people, and his perennially hard-hearted countrymen hated and brutalized him for decrying the wickedness that incurred it. Jeremiah wanted out of his miserable ministry. But the only thing harder than speaking for God was not doing so. “If I say, ‘I will not mention him, or speak any more in his name,’ there is in my heart as it were a burning fire shut up in my bones, and I am weary with holding it in, and I cannot” (Jer. 20:9).

There is something utterly compelling about the idea of God and something irrepressible about the sincere belief that God exists. If we’re Christians, shouldn’t our souls dance if we truly believe that God has spoken and we have access to his words, or break down and cry depending upon what God has to say? And that’s exactly how we can spot the sometimes unseen disconnect between true faith and faith that’s all (sincere) talk. Our true regard for God is revealed in our regard for his Word.11

There’s a sad but clear logic to it: If you don’t care much about God, you won’t care much about what he says.12 On the other hand, if you’re enthralled with God, you’ll hang on every word he says as if your life depends on it—because if God is real, it does. Jesus says: “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God” (Matt. 4:4). And that’s what makes the big picture of allegedly Bible-believing Christianity in America so bleak.

It’s common in contemporary Christian America to resent a 10-minute drive to church and to spend sermon time silently willing the preacher not to exceed the unwritten but deadly serious 20-minute time limit. True, some pastors are boring. So are some writers, and people like me who are both are the worst! But if the presentation is at least a credible effort from a credible source—someone who believes that the Bible is God’s Word, has prayerfully and studiously prepared to preach as such, and who sincerely cares for the people listening and speaks to their hearts—couldn’t we muster some patience? After all, the Bible is the Word of God. Why does God’s Word not get more love from people who claim to love God? Jesus says that God’s Word is vital for life; many Christians seem to disagree.

Sociologist Dr. Jonathan Hill notes that only eight percent of young people in the United States who self-identify as Christians actually read their Bible with any regularity.13 Of course, stats can vary depending on how you define terms and ask questions. So let’s make it personal: if you’re a Christian, how much practical difference would it make to your daily routine if you no longer had access to the Bible?

Maybe there’s a happy, or at least hopeful, irony at play in all this. Perhaps many Christians in this culture, despite constant access to God’s Word, have never truly approached the Bible as God’s word. That’s unnerving, because it means that people who claim to love Jesus may not know Jesus as the Bible proclaims him. But that also means there’s hope. It means that our “meh” attitude might not be directed so much toward Jesus and his Word as toward our personal perceptions of them as perpetuated by the church. This is exactly why God gave us books in the Bible like James, to cut through the calluses of our self-deceit, to show us what’s healthy or rotten in our souls beneath them, and to reveal what we truly believe—or don’t.

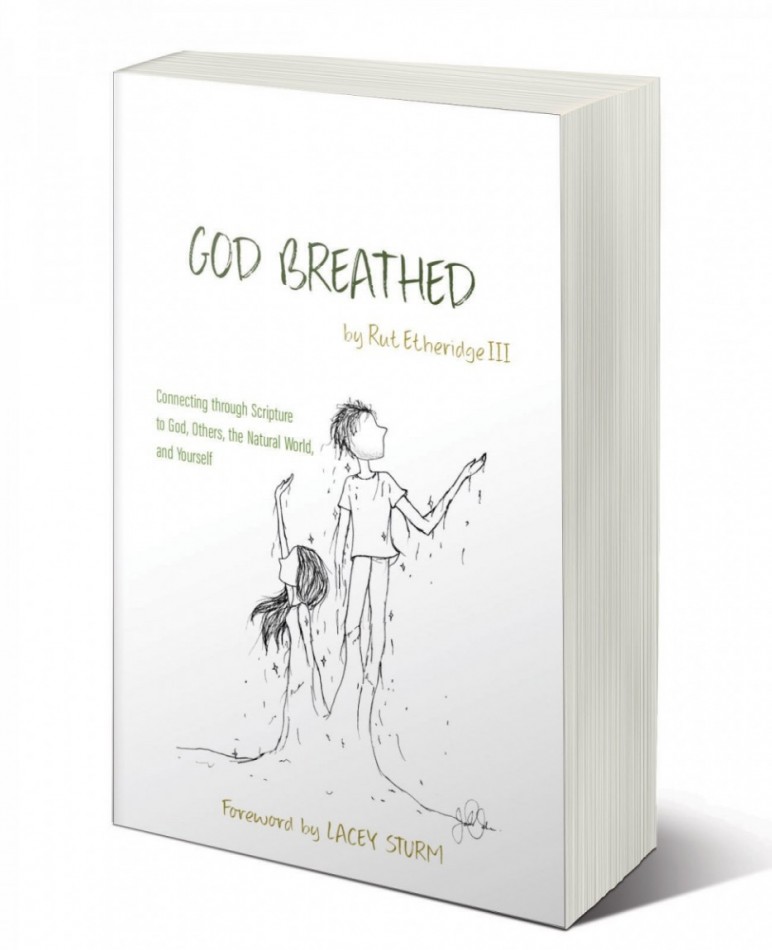

Rut Etheridge III is assistant professor of biblical studies at Geneva College. Prior to this, Rut taught high school and pastored a church. He holds a B.S. in Bible and philosophy and an MDiv; he is currently pursuing PhD studies in theology. This article is an excerpt from chapters 1 and 2 of Rut’s newly released book God Breathed (2019, Crown & Covenant Publications).

Notes

-

A really bad statement loses an idea’s meaning entirely. But it’s a really bad idea whose statement can’t help but express the exact opposite of the idea’s intent. Some understandings of truth would blame this problem of internal incoherence on the limits of language. It’s common in “postmodern” times to assert that words cannot convey truth and that they have no knowable meaning except what the reader/hearer ascribes to them. Thus, no real communication is possible. But these views fall prey to the same suicidal inconsistencies of the incoherent ideas they’re seeking to exonerate. Notice, it takes words to express the idea that words can’t communicate, and it’s easy to understand what’s meant by those words. For example, “It’s impossible for you to understand this sentence.” You understood it, didn’t you? Words convey meaning, and meaning can be known. ↩︎

-

See especially the work of D. A. Carson, The Gagging of God: Christianity Confronts Pluralism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996) and The Intolerance of Tolerance (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012). ↩︎

-

Possibly taking a second-place finish to the church’s condemning Galileo in relation to his teaching that the earth is not the center of the cosmos. This condemnation is considered exhibit A of Christianity’s refusal to accept truth if it contradicts church dogma and therefore a blunder of cosmic proportions in the historical case for the intellectual credibility of the faith. See Owen Barfield, Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1988), especially chapter 7, p. 50 and following, for the contention that the Galileo saga was really more about epistemology than astronomy, that the church’s concern was not so much a heliocentric view of the cosmos as the danger of elevating scientific hypotheses from providers of analysis and explanation of empirical reality to arbiters of truth, even, potentially, moral truth. Even if current scientific theory explains physical phenomena satisfactorily (for now), should we really call it truth? And that raises the further, and deeper question: could popular scientific reasoning really provide humankind with everything in life worth knowing? Rationalism answered yes and has taken Western history and humanity to many unfortunate, dehumanizing places as a result. See chapters 3 and 4 of this book. ↩︎

-

Referencing Romans chapter 1, Descartes writes: “…we seem to be told that everything that may be known of God can be demonstrated by reasoning which has no other source than our mind.” From his “Meditations on the First Philosophy—Dedicatory letter to the Sorbonne” in Forest E. Baird, Walter Kaufmann, Philosophical Classics: Volume III, Modern Philosophy, Second Edition (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, Simon & Schuster, 1997), p. 21. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 19. ↩︎

-

Apostle comes from a Greek word meaning “one who is sent.” The twelve apostles were leaders of the highest authority in the early New Testament-era church. All of them knew Jesus personally and interacted with Him following His resurrection. The Apostle Paul’s interaction with the resurrected Christ was a traumatic one, coming in the context of a violent, confrontational, prophetic vision. See Acts 9. ↩︎

-

This title means “the second giving of the law.” It chronicles the journey of the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt to the land God promised to provide them as their own. Because the all-talk faith that James decries was rampant among so many of them, this journey included 40 years of a sort of pre-habitation exile from the Promised Land. ↩︎

-

James would tell us to give the good seat that we secured to someone else, especially a socially marginalized person who may come to worship (see Jas. 2). But we could still camp out for that purpose! ↩︎

-

The Bible teaches that humans share certain character qualities with God, which allow us to safely absorb some of that heat and to give it productive vent. Sometimes we try to harness that god-like fire as if we started it, as if it exists to serve us, and we set ourselves up for flameouts. ↩︎

-

For a humorous example of this principle played out in a deadly serious situation, see the Old Testament book of Numbers, chapters 22–23. The saga detailed here is rich with irony and even includes good fodder for people particularly concerned about animal rights. See chapter 10 also on the latter. God loves all of creation, the “creatures” included (Ps. 104, 145, John 3:16, Rom. 8). ↩︎

-

Pastor and theologian John Murray puts it perfectly: “As will be our conception of Scripture, so will be our conception of the Christian faith.” John Murray, Collected Writings, Volume 3 (Carlisle: Banner of Truth, 1982), p. 256. ↩︎

-

Kevin Vanhoozer deals helpfully with the issue of theological prioritization in First Theology: God, Scripture and Hermeneutics (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2002). ↩︎

-

See Jonathan P. Hill, Emerging Adulthood and Faith (Grand Rapids: The Calvin College Press, 2015). ↩︎