You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

Quarantine. Wearing a mask. Keeping safer at home. Pandemic. No public worship. Closing and reopening. Many of us think of these far more often than we did a year ago, since we have never experienced anything comparable to COVID-19. But many of us have heard about the great Spanish Flu pandemic at the end of World War I, and we know that a lot of these concepts were important then.

Today, most of our churches are in medium-size cities or suburban areas, with some country churches and few urban churches. The church of 1918 was quite different. Most congregations on the coasts were in urban areas. There were 10 RP congregations and 1,200 members in the Boston, New York, and Philadelphia metro areas. Most of our churches between the Appalachians and the Rockies were in the countryside and small towns.

Currently, in terms of the pandemic, many of the worst-hit areas of the United States have been urban. Rural areas have often been less impacted, but most of our churches in all settings have closed temporarily. Was it the same a century ago?

Session and presbytery minutes from 1918, together with articles in the church paper, the Christian Nation, reveal that the church faced significant challenges, both in rural areas and in large cities. However, the church of 1918 experienced more variations in restrictions than in 2020. This is partly because of how the virus spread, and partially because local governments made most decisions on quarantines, closures, etc.

Many churches couldn’t worship as normal in 1918, but some could. Iowa’s government closed all churches, and Denison, Kan., also reported a state closure. Congregations such as Oakdale, Ill., Jonathan’s Creek, Ohio, and Hetherton (Johannesburg, Mich.) closed for several weeks, as did many in major cities.

Other churches experienced partial closures. Bellefontaine, Ohio, experienced a light first wave, so a quarantine imposed in October was lifted a month later, only to be restored when the disease returned with far greater force. Meetings continued at Beulah, Neb., and York, N.Y., until members started being infected.

Like today, worship at home became important. At Walton, N.Y., the pastor and an elder rotated from home to home, leading small services. Seattle, Wash., reported that “every family in our congregation has had the Light of God’s Word and the precious privilege of family worship.”

What happened in Canada? Regina, S.K., and Winnipeg, M.B., were closed for more than a month, while Almonte, Ont., was able to worship every week. These small churches made no reports at all: Content, Alb.; Lochiel, Ont.,; Barnesville, N.B.; St. John, N.B.; and Cornwallis, N.S.

Unlike in 2020, parts of the northeastern U.S. had weaker restrictions in 1919. Second Boston RPC planned for Walton, N.Y.’s pastor to assist at their communion; and, when he was quarantined, they proceeded unassisted.

Farther west, travel continued. After future minister C.T. Carson conducted one victim’s funeral at Clarinda, Iowa, on Oct. 7, he found time to conduct another at Bethel, Ill., seven weeks later, just before moving to Colorado to be ordained. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary student J.F. Carithers was sickened in November while attending the seminary. But his parents were able to travel from Sharon, Iowa, to reach his bedside before his death, and they took his body home for burial.

One aspect familiar to us today was the pandemic’s effect on funerals. Many of us remember that Rev. John Tweed had only a small graveside service after his death in May 2020. The same was true in 1918. Many obituaries in the Christian Nation report small private funerals, whether for A.J. McFarland (the oldest minister of the church ), young Carithers, or lesser-known members.

At the same time, some families deemed funerals important enough to risk infection. When Margaret Young of New Castle, Pa., died, the funeral was held at her home, although “several other members of the family were ill at the time with the influenza.”

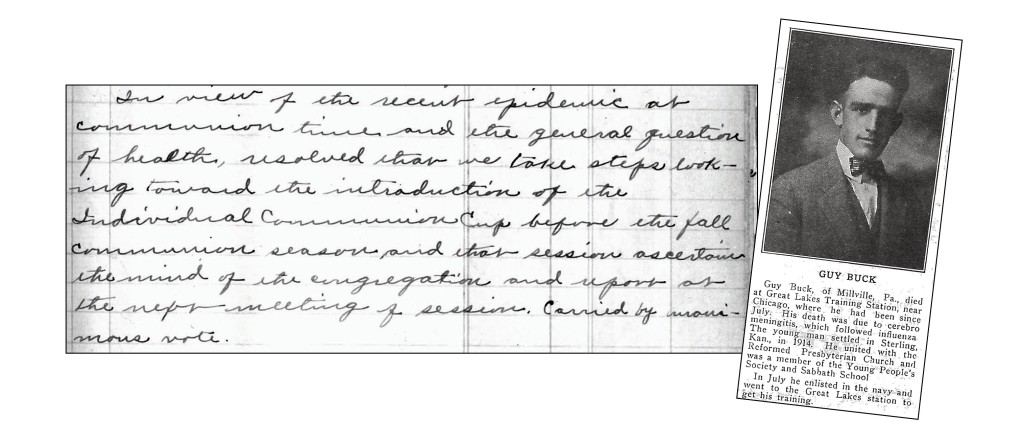

More than 400 church members were in the military, and Kansas Presbytery tried to send ministers to preach at Fort Riley (near Manhattan). Many members were infected while in uniform. Reports from Clarinda, Iowa and Sterling, Kan., noted that members died at faraway military camps, and many congregations reported that one or more of their boys in khaki had caught it.

Conversely, other group settings resulted in fewer infections. Geneva College closed after about 50 cases were reported, and only one student, a member at New Alexandria, Pa., died.

The church’s other educational programs closed. The seminary closed after J.F. Carithers was infected in November, and it did not reopen until after his death. In Selma, Ala., the Southern Mission School closed on Oct. 9 and stayed closed through December. Several workers at the Indian Mission School at Cache Creek, Okla., were sickened, and one of the congregation’s deacons died. Workers at the shuttered Philadelphia Jewish Mission reported having to turn away children who wanted to learn. Even in South China, a teacher in the girls school at Lo Ting died of flu in 1919.

The Christian Nation rarely depicts individuals or churches disputing governmental responses to the epidemic. All the minutes I have seen show churches meeting whenever possible but carefully adhering to regulations.

If any churches denounced regulations, the paper’s editor John Pritchard may not have been interested in printing their reports, as he experienced the disease in October. However, three months later he printed an article by a future editor, Raymond Taggart, urging that churches be “considered one of the essentials for the health of the community” because prayer was necessary. One of the Boston ministers disputed church closures, but he rejected the city’s classification of churches with saloons and theaters, not church closures per se.

At least one congregation changed part of its worship service as a result of the pandemic. Historically, each congregation used a common communion cup, but Synod had allowed individual cups in 1912, citing hygiene and holding that biblical references to “cup” concentrated on the contents, not the physical cup. Not all congregations changed immediately, so common cups could still be found in 1918. In Iowa, the Hopkinton congregation was one of these; but after their communion coincided with a wave of influenza, the session decided that it was time for individual cups.

Nothing like today’s family conferences was canceled because the system didn’t yet exist. Philadelphia Presbytery’s three churches normally held joint services and communion seasons; but the 1918 joint services were impossible, and communions were postponed. Because the worst wave of the disease occurred at year’s end, Synod met as normal, but presbytery meetings had mixed results. More Americans than Canadians attended the September meeting of Rochester (now St. Lawrence) Presbytery at Almonte. Military alliance promoted wartime travel between the countries, and, unlike in 2020, the pandemic didn’t close the border.

Pittsburgh Presbytery was less successful. They planned to meet in October at the remote Rehoboth RPC, northeast of Pittsburgh, but the minutes suggest that only the Rehoboth elder and the minister from Parnassus (now Manchester) attended.

Pacific Coast Presbytery planned an October meeting at Seattle, but sessions gradually realized it wouldn’t happen. Hemet, Calif., appointed a delegate, but Santa Ana, Calif., and Portland, Ore., didn’t. Since public meetings were prohibited, the presbytery meeting ended up being just Seattle’s delegates, and they postponed the meeting until December. Again, Portland and Santa Ana sent no one, and no California minister except P.J. McDonald of Los Angeles made the long trip north.

You may be coping with the difficulty of maintaining contact with fellow church members when no public meetings are possible, or you may be rejoicing that restrictions have been loosened and your church can return to more normal gatherings. Congregations in 1918 often reported weariness of sickness and death from Spanish Flu, but they consistently showed a desire for worship: rejoicing that it could resume, mourning that it could not, giving thanks that private worship could continue in homes, and eagerly anticipating the day when public meetings would again be safe. Let us emulate the church of a century ago, praying for safety and eagerly anticipating when we can make our pilgrim journey and see the Lord’s house.

Nathaniel Pockras is an electronic resources librarian at Liberty University in Lynchburg, Va. He is a member of Grace and Truth RPC, a mission church of the Presbytery of the Alleghenies in Harrisonburg, Va.