You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

The Windmill Pete Series

Bob Hemphill | Morris Publishing, &7.50 each | Reviewed by Russ Pulliam

Bob Hemphill has good memories of growing up in Beaver Falls, Pa., in the 1950s and 1960s.

Those memories will come back for Geneva alumni if they read his Windmill Pete series of stories to children or grandchildren. The eight books, each under 100 pages, include a college, a big river, and a couple of creeks running into the river.

For those who remember Chip Hilton or Sugar Creek Gang stories, they also will hear some fun echoes in this series. They are exciting for adults as well when read aloud to children or grandchildren.

Ball Hogs, the last one to be published, came out in summer 2023 and is number seven in the series. As the title suggests, Donnie, Dusty, and Sleepy have to learn to give up scoring records, share the ball, and make teammates successful with good passing. They get kicked off the team, and the remnant goes on to win the last game of the season against an important rival.

The first in the series, Lost in the Woods, tells how Chip’s little brother, Pee Wee, got lost as he lagged behind his big brother on a hike. Pee Wee spends the night along the river until he gets rescued in the morning by a patrol boat.

In Free Fall Down Federal Hill, the characters try to break their speed record for racing up the hill and back down.

Like the Chip Hilton series, some of these stories take a reader through a baseball or football season. Can they repeat an unbeaten record in the next season of basketball? (Six and Zero.) Or find out how painful it feels to be Cut From the Team. (The books are available at crownandcovenant.com or windmillpete.com.)

Hemphill’s stories are realistic. Other teams knock a kid unconscious with a vicious body slam. Basketball is a contact sport in these stories.

Lamar Small drowns in the river after slipping off the dam where several boys were playing. The funeral allows Hemphill to include a short summary of the gospel, with a funeral sermon.

Hemphill remembers his own childhood to explain his literary bent. “My parents read Sugar Creek Gang stories to us when we were children,” he noted. “That got me started. My two brothers and I would write stories as we went on trips with our parents.” Two broken arms in one year slowed Hemphill down athletically, but he learned to use his left hand better in sports and started reading the Chip Hilton books in a time of recovery. Hilton is almost too good to be true. Chip is a three-sport athlete whose father has died, and the books emphasize character as well as winning games.

The Sugar Creek Gang books were written by Paul Hutchens, who had to stop preaching. So, he wrote from a different kind of pulpit. “I was a better boy because of what was planted in my mind,” Hutchens recalled of childhood reading when he lived near the real Sugar Creek in rural Indiana. “I was eventually a better man because of good books.”

Hemphill would agree with that sentiment. “Writing has given me an outlet for the gospel to a broader audience and an opportunity to shape young lives beyond a local congregation,” he noted.

Hemphill wrote his stories as a pastor in Selma, Ala., then started publishing them in 2007. He was pastor of Selma RPC in the 1980s and early 1990s, then pastored Westminster, Colo., RPC, before leading the planting of Laramie, Wyo., RPC.

He is officially retired as a pastor, but not as an author. Now he has another pulpit, with a congregation of young readers.

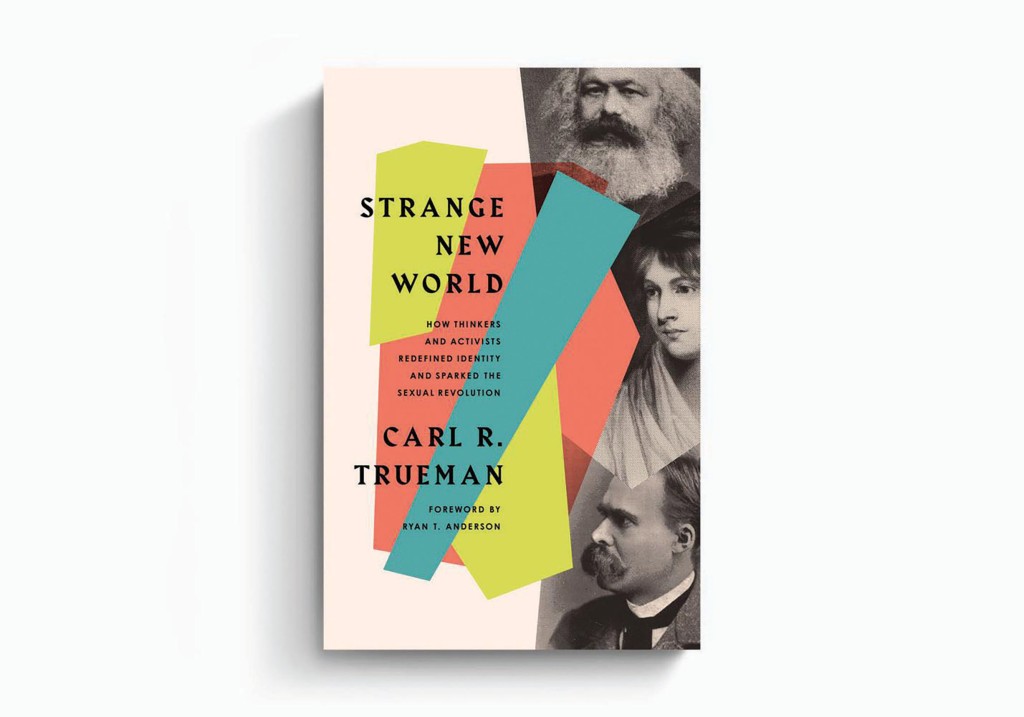

Strange New World: How Thinkers and Activists Redefined Identity and Sparked the Sexual Revolution

Carl R. Trueman | Crossway, 2022, 208 pp., $17.99 | Reviewed by Fiona Buck

Why do some people believe that advocating for the traditional view of marriage is irrational bigotry? Why do some believe that harassing a speaker for their political views is acceptable, even virtuous? Why do some believe that school boards, not parents, should make the crucial decisions about children’s education, particularly in matters of sexuality? And why, when I fill out paperwork for my gynecologist, am I asked my sex assigned at birth? As the title of Carl Trueman’s 2022 book aptly puts it, we live in a “strange new world,” one that can feel utterly incomprehensible at times.

Trueman’s purpose in Strange New World is to explain our seemingly bizarre cultural moment. Trueman argues that there is a historical and even logical progression that led us here, and the key to understanding our times is to understand the modern notion of the self, i.e., what most people believe it means to be human and where the “real me” resides. “Modern man,” Trueman claims, “seeks to be ‘true to himself.’ Rather than conform thoughts, feelings, and actions to objective reality, man’s inner life itself becomes the source of truth” (p. 12). The prioritizing of psychology and linking of identity with inner desires does much to explain our cultural moment.

In the book’s nine chapters, Trueman traces the philosophical heritage of the modern self by looking at such thinkers as Rousseau, Marx, and Freud. Additionally, he explores the role of technology in making the modern self seem plausible. In the seventh and eighth chapters, Trueman outlines how the notion of the modern self has played out in the recent and rapid ascendancy of the LGBTQ+ movement, and how it is playing out in conflicts over freedom of religion and of speech. Finally, Trueman closes with suggestions for how Christians should live in light of these developments.

Strange New World is Trueman’s attempt to make the main ideas of his 2020 book The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self more accessible. I believe he succeeds in this. Not only is Strange New World approximately half the length, but Trueman does an excellent job explaining the various ideas. Trueman also is more willing to offer commentary at points rather than just description. Understanding the historical development of the modern self has helped me to think more charitably about those whose beliefs otherwise would make so little sense to me.