You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

The Reformed Presbyterian Church was active and outspoken in the abolitionist movement even before the U.S. Constitution was written. Because of its background and convictions, the church held what author Robert Copeland calls “an outsized role in the crusade against American slavery.” It may have been the first denomination to enforce an absolute prohibition against slaveholders in the church.

This spring, Crown & Covenant Publications will release Candle Against the Dark, a new book by Copeland about Reformed Presbyterian involvement in the abolitionist movement.

Copeland builds on the body of research that D. Ray Wilcox submitted as his thesis at the University of Northern Colorado over 70 years ago. It is chock-full of stories and original source material. This excerpt focuses on Reformed Presbyterians’ work with the Underground Railroad.

—Editor

Covenanters and the Underground Railroad

Bearing in mind their history, Reformed Presbyterians and others of Scottish and Scots-Irish descent loved liberty and generally gave strong support to the antislavery crusade. Wilbur H. Siebert identified some Scottish communities as particularly active in the Underground Railroad, singling out those in Morgan and Logan Counties, Ohio, and in Randolph and Washington Counties, Ill. “There were some New England colonies in the west where anti-slavery sentiments predominated. These, like some of the religious communities, as those of the Quakers and Covenanters, became well known centres of underground activity.” Some of the slaves did not go to Canada but remained in communities where the “presence of Quakers, Wesleyan Methodists, Covenanters or Free Presbyterians gave them the assurance of safety and assistance.” 1

Describing the operation of the railroad in Illinois, Siebert said, “The few lines known in southwestern Illinois were developed by a few Covenanter communities.” Speaking generally of the unhelpful attitude of the churches toward the slaves and free Black citizens, he points to two conspicuous exceptions:

“It is a fact worthy of record in this connection that the teachings of two sects, the Scot[s] Covenanters and the Wesleyan Methodists, did not exclude the negro from the bonds of Christian brotherhood, and where churches of either denomination existed the Road was likely to be found in active operation.” 2

The frequent mention of the Covenanters in Siebert’s account is an indication that they were not insignificant in the Underground Railroad. Most of the routes he had discovered were in Ohio, where he had done the majority of his research. There were also extensive lines in Pennsylvania, and some through Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, and even Kansas. Railroad traffic flowed heavily through Philadelphia to New York and thence to Albany and Rochester. A map of known Underground Railroad “stations” matches rather well with the locations of the Covenanter congregations at the time.

Urban Congregations

Large cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati were popular centers of the railroad because fugitives could easily meld into the population. Covenanters in the cities were also active in the operations. N.R. Johnston, at that time the stated supply of the Cincinnati congregation, describes one of the successful incidents of their cooperation with Levi Coffin. 3 John L. McFetridge, a Covenanter who worked in a lumber yard in Covington, Ky., came to Johnston at church one day, telling him of a group of slaves that had arrived in Covington and wanted help to cross the Ohio River and through the state. Johnston met secretly with one of the slaves, Patterson Randall. “I laid the whole matter,” he writes, “before three well-known friends of freedom, viz. Hugh Glasgow, my host (than whom no truer friend of the slave ever walked the streets of Cincinnati), a leading colored business man, and that noble and well-known friend of human rights, Friend Levi Coffin.”

These four men arranged and carried out the river crossing by boat, as there was no bridge on the Ohio River at Cincinnati until the completion of John Roebling’s suspension bridge in 1866. They saw them safely through Cincinnati and seven miles beyond the city to the first railroad station. Johnston and Glasgow went out the next day to see if the slaves were safe, climbing a ladder to a secret room above a double corn crib to visit them. Later the same winter, Coffin asked Johnston about arranging with some of the Covenanters of Indiana or Illinois about the ill-fated aiding of the family of Peter Still. 4

In Philadelphia, too, the Covenanters were active. James M. Willson, pastor of First RP Church from 1834 to 1862, was president of the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, and his church was a station on the Underground Railroad. Members, who at the time were children, later remembered “looking back and up at the balcony during services and seeing a row of black faces peering over the edge of the balcony. This gallery was frequently used as a hiding place for fugitives.” 5

Western Pennsylvania

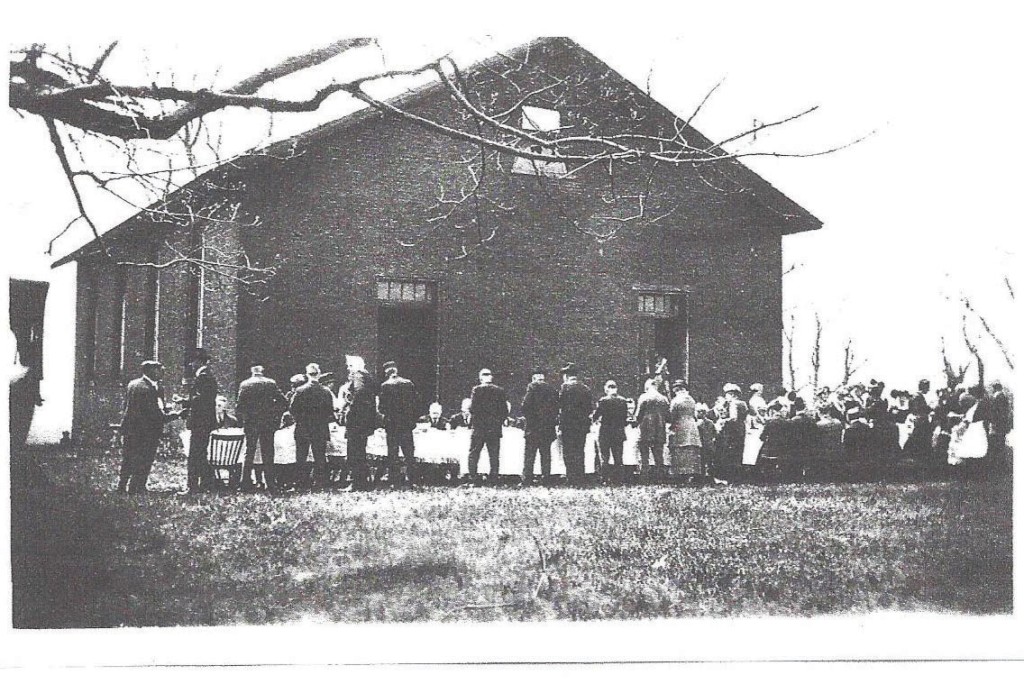

In western Pennsylvania, one of the Covenanter congregations active in the railroad was Brookland, a rural church in northern Westmoreland County. At one time, the pastor, Robert Reed, concealed a fugitive from North Carolina in his study for a week. This fugitive was “almost white”; his father was a planter and congressman. While the fugitive was there, two slave hunters rode past the house, carrying whips. Reed’s wife, Mary Walkinshaw Reed, was almost paralyzed with fear. A few nights later, one of the ruling elders, David McElroy, took the fugitive to the home of a Mr. White, an elder in the Rehobeth congregation in Jefferson County. Other stations in Westmoreland County included the home of Robert Sproull near Brookland and that of Rev. Robert B. Cannon in Greensburg. 6

“Mary Walkinshaw, as a girl, saw both colored men and women at her grandfather’s home. Her own home became a station for the fugitives on their perilous journey. It was just before the Civil War that Billy Shafer, footsore, hungry, and sick, came to her door. He had walked all the way from the home of Dr. Cannon, in Greensburg, in one day. She took him in and ministered unto him. She held him in her arms when he died. His last words told of his sorrow for the trouble he had caused her, and his gratitude for her kindness. The men of Brookland buried him in the old cemetery. He had reached the end of life’s journey. Its hardships were over. The land of eternal freedom and rest had been reached.” 7

Covenanter congregations in Lawrence, Mercer, and Crawford counties were also deeply involved. In 1853, Rev. Thomas Hanna became pastor of the Slippery Rock congregation, located at Rose Point. Hanna lived in New Castle and was active in receiving runaway slaves and forwarding them to safe places farther north in Mercer County. Other members involved included Rev. James Blackwood, George W. Boggs, John Love, David and Jane Pattison, Robert and Rachel Speer, and Matthew and Sarah Stewart. Thomas Wilson, an elder in the congregation, and his wife Margaret farmed near Rose Point and were very active in concealing fugitives and furthering their flight. A number of members lived near Portersville, one of which was George H. Magee, an elder in the church. Magee built a wagon with a double bottom to conceal runaways, and in the basement of his house, he built a small room with one door, one window, and a dirt floor. Like many homes in western Pennsylvania, his was on a steep hillside with the front door at the road level; thus, the cellar door(s) led directly out at ground level. His son John Magee later recalled an incident:

“I remember two men, supposed to be slave hunters, being entertained in my father’s house overnight, when in the basement there were six slaves being hidden. The wood-burning fireplace was plentifully supplied with fuel, and my mother was carrying provisions and bedding the back way for these people. Two small children were in the group but not a sound came from them.” 8

Beaver County, with a plethora of Presbyterians, was a major hub in helping the slaves who came into the state through Washington County and Pittsburgh. Covenanters of the Little Beaver congregation near New Galilee participated actively in the UGRR.

Notes

-

Siebert, Underground Railroad, 92; 90; 325. ↩︎

-

Siebert, Underground Railroad, 115; 32. ↩︎

-

In Presbyterian governance, a “stated supply” is a minister who is assigned by the presbytery to minister to a vacant congregation and to serve as moderator of the session on a short-term basis, while a pastor is one who has been called by the congregation and installed by the presbytery, and usually serves as moderator of the session by right rather than by special appointment. ↩︎

-

Looking Back from the Sunset Land, 115-120. ↩︎

-

Letter, Dr. Samuel E. Greer to D. Ray Wilcox, Feb. 24, 1948; in Wilcox, 110 fn2. Greer, pastor of First Philadelphia from 1922 to 1950, said that he remembered the oldest members of the congregation telling of this experience. Dr. T.P. Stevenson, pastor of the congregation from 1863 to 1912, was also said to be deeply involved in helping fugitives. ↩︎

-

The Centenary of a Covenanter Society, 1822-1922, Being a History of the Brookland Congregation (1922), 41-43; quoted in Wilcox, 110 fn3. ↩︎

-

Centenary of a Covenanter Society, 43. Mary Walkinshaw (1836-1925) was the daughter of Rev. Hugh Walkinshaw, pastor of Brookland from 1835-43, and his wife Lydia Jean Sproull (daughter of Robert Sproull). She married Rev. Robert Reed, pastor of Brookland from 1854-1882. The grandfather mentioned in the account would be Robert Sproull. ↩︎

-

Susan Linville and Elizabeth Dirisio, In Hot Pursuit: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad in Lawrence County, Pennsylvania (New Castle, PA: Pokeberry, 2016). See pp. 66-67, 73-75, 81-83, 102-104, 128-129. Like many houses in western Pennsylvania, the Magee home was built on a steep slope, so that the basement exit was at ground level. ↩︎