You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

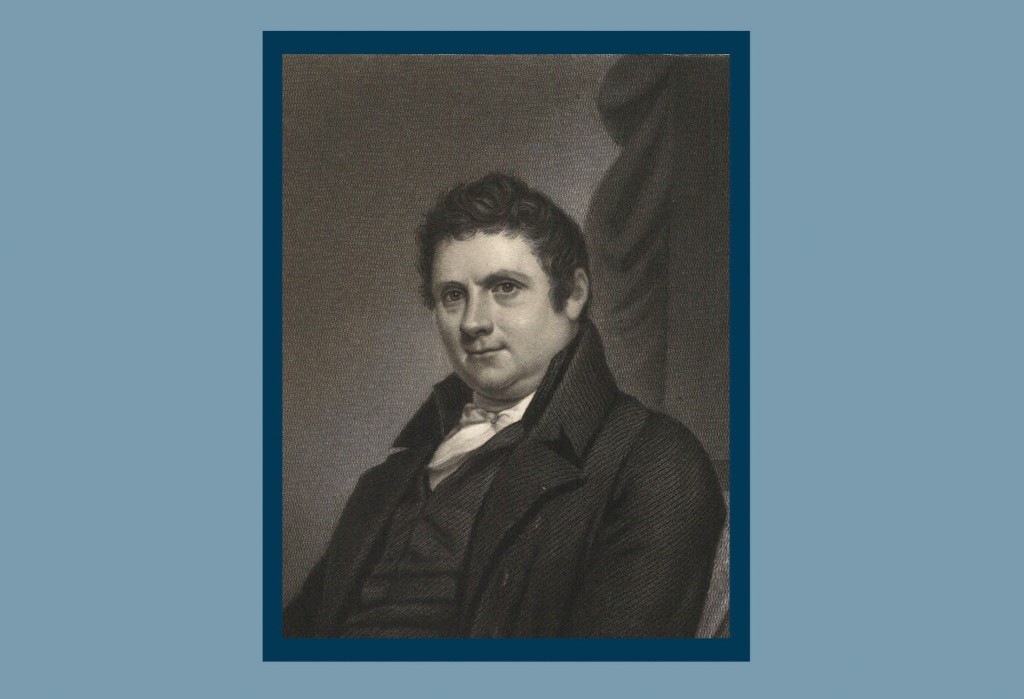

Unless faithfully preserved and periodically rekindled, the memory of great men and their accomplishments soon passes from the consciousness of people. Even among those well acquainted with the contours of American Presbyterian history, the name of Alexander McLeod will likely ring no bells. Yet, in the first part of the 19th Century, he was one of this country’s most widely respected and read preachers of biblical orthodoxy.

His Ecclesiastical Catechism—today, one of his least-known works—was published at the height of a period of intense debate over church government. It catapulted the young preacher to prominence, not only in New York where he was a Reformed Presbyterian pastor, but across the English-speaking world. No fewer than 12 editions of that work came from the press on both sides of the Atlantic. Other publications—on such diverse subjects as African slavery, the War of 1812, the prophecies of Revelation, and personal godliness—passed through multiple editions and survived him in print by a generation. This was followed by a century and a half of silence. The rediscovery of Alexander McLeod is arguably long overdue! 1

Alexander McLeod was born on June 12, 1774, at Ardcrishnish on the island of Mull, off the west coast of Scotland. His father, Rev. Neil McLeod, who died when Alexander was five, was the parish minister. Samuel Johnson had visited the manse on October 20–21, 1773, and declared Mr. McLeod to be “the clearest-headed man in the Highlands.” His ability evidently descended to the son.

McLeod was what the Scots called “a lad o’ pairts.” After receiving a classical education in Bracadale, on the Isle of Skye—still today not exactly the center of the educational universe—and having lost his father at 5 and his mother at 12, Alexander emigrated in 1792, age 18, and settled among the Gaelic-speaking Scots of the Mohawk Valley in upstate New York, where he became a teacher of Greek. It was there that he came in contact with the Reformed Presbyterian Church in the person of the Rev. James McKinney (1759–1802), an Ulsterman preaching to the scattered societies of Covenanters from Scotland and Ireland. McKinney proclaimed a full-orbed doctrine of the kingship of Christ over men and nations. He pointed out the secular nature of the recently ratified U.S. Constitution (1787–90), and insisted that civil government was a divine institution called to serve God according to his Word, the Bible, which teaching was to be appropriately applied to the state’s sphere of responsibility, while fully recognizing the proper relationship between church and state as distinct institutions of God. 2

The Reformed Presbyterian Church—the church of the Covenanters of Scotland and Ireland—was organized as an American denomination on Feb. 21, 1798, in Philadelphia. McLeod was licensed by the new presbytery to preach the gospel, together with Samuel B. Wylie and John Black. In 1801, he was ordained to serve as pastor in Coldenham, N.Y., with responsibility for New York City, but in 1803 he became the minister of the New York congregation exclusively. There he exercised a fruitful and expanding ministry for some thirty years. It is a testimony to his standing in the Reformed community that he received at various times invitations to pastor the Reformed Dutch Church on Garden Street, to succeed his friend Dr. Samuel Miller (1769–1850) at First Presbyterian Church, Wall Street, and to serve as a professor and vice president at Princeton, with a view to succeeding to the presidency of that great institution. He nevertheless remained a Reformed Presbyterian and pastor of the New York RP congregation until his death at the age of 58 at the hour of worship on Sabbath, Feb. 17, 1833.

He knew affliction all his life. At 5, he lost his father; at 12 he was an orphan. Only 4 of his 11 children survived him. His congregation was visited in the cholera epidemics that periodically scourged New York in those days. He was a sick man for the last decade of his life. These trials blessed him, however, and his many writings bear testimony to a fragrant evangelical humility. Gardiner Spring (1785–1873), minister of the Brick Presbyterian Church, said of McLeod that he had “the most philosophical and discriminating mind” in the ministerial association that included Samuel Miller and Spring himself, and described his preaching as characterized by “rich thought and great earnestness.”

His writings bear this out. Like other expatriate Scots of recent times—one thinks of the 20th Century John Murray and the contemporaneous Sinclair Ferguson, both of Westminster Theological Seminary—Alexander McLeod makes his points with a weighty and meditative simplicity that so obviously rests on deep experience of the truth of God’s Word as to leave us wondering why we never quite saw it that way before! This is abundantly clear in his celebrated tract, Messiah, Governor of the Nations of the Earth, first published in 1803 and still in print some 50 years later. It was clearly designed as a definitive yet popular statement of the Bible’s teaching on the kingship of Christ over the nations.

It also reveals in the author the contours of a clear mind that is powerfully furnished with a lively grasp of biblical truth and a vigorous mastery of Reformed theology. His reasons for the necessity of Christ’s kingship demonstrate this so well. The effectiveness of carrying out the Great Commission (Matt. 28:18–20)—the conversion of lost people to Christ, the satisfaction of Jesus’s sufferings, and the Lord’s protection of believers and the Church—all depends, he argues, upon the actual, effectual, and sovereign kingship of the risen Christ. If He is not Lord of all, can He truly be Lord at all?

He carefully teases out the objections often made against the doctrine of Christ’s lordship over the nations and, point by point, shows that the common notions of separation of Christ and the state—that is, as an autonomous, religiously neutral institution on the one hand, over against a non-involved spectator-Savior who is lord of the soul but not of the universe—are utterly unscriptural. He irrefutably shows that nations must bow to Christ and honor Him, that the church must call men and nations to obedience to Christ as King.

Perhaps most pointedly, he notes that it is “despicable faint-heartedness” in Christians when they are unmoved by the spectacle of “the crown of the nations being taken from the Mediator’s head,” apparently unconcerned about laboring to rectify the situation. McLeod, in common with the Reformed divines of his time, was what we now generally call a postmillennialist, although he never used the term. He was looking for the extension of God’s kingdom upon earth before the coming of the Lord. He had no illusions about the difficulties of the task, but was imbued by a desire to change the world by the preaching of the gospel.

The legacy of Alexander McLeod is the call to preach the whole counsel of God to a world in need of the good news of the gospel and to live as the people of the King—Jesus, the only Redeemer of God’s elect. As the writer to the Hebrews says of righteous Abel, so we may say of the writer of the various pieces in this volume, that, “through his faith, though he died, he still speaks” (Heb. 11:4).

Notes

1. A full memoir of McLeod does exist: Samuel B. Wylie, Memoir of Alexander McLeod, D.D. (New York: Charles Scribner, 1855). This was edited for publication by McLeod’s son, Rev. John Niel McLeod, after Wylie died in 1852. This work was appointed by the “New Light” RP Synod in 1833 and has the appearance more of a book cobbled together—after more than 20 years of a wait—by family and friends, than a well-researched biography of the man and his life. There is plenty of scope for a modern biographical assessment of McLeod’s life and significance.

2. James McKinney, A View of the Rights of God and Man in Some Sermons (Philadelphia: 1797), 64 pp. McKinney was the founding minister of the indigenous American Reformed Presbyterian Church when it was organized in Philadelphia in 1798. He intended to publish a sequel to the Rights of God, but although this was said to be written and ready for publication at the time of McKinney’s sudden death, age 45, while on a preaching trip, it was somehow lost and never appeared in print. See W. M. Glasgow, History of the Reformed Presbyterian Church in America (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2007 [1888], p. 604).