You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

In January 1919, my great-grandfather Edwin Howe was finishing his stay at a sanitorium for tuberculosis patients when the Spanish Flu swept through it, leaving my great-grandmother a widow and their only child fatherless. Thus the memory of America’s last serious pandemic stayed alive in my family, for my grandfather and for his children and grandchildren.

We should have known this was coming. During the century since the Spanish Flu, our world has become almost unbelievably interconnected. Typical employees now have a commute of over 15 miles to work, and families routinely travel to school, church, and the grocery store by motor vehicle. In the early 2000s, without large parts of the world “off-limits” (as the Soviet bloc was during the Cold War), the global volume of travel grew even more. In 2009-2010 the world saw the outbreak of a relatively mild H1N1 pandemic. The United States was largely spared, but life in China and other countries was seriously affected for a time, and thousands were sickened or died.

In November 2019, it appears that the SARS-Cov2 virus, a.k.a. COVID-19 or “the coronavirus,” jumped from a bat to a human being in Wuhan, China, and we were off to the races.

January–February

Word comes (mostly via friends of the congregation living in China) that a serious respiratory disease has broken out in Wuhan, and that the Chinese government is resorting to drastic measures to contain it. Reports of strict stay-at-home orders, rationing, and many deaths trickle in, hampered by the People’s Republic’s repressive control of its people and media. In mid-January the U.S. starts screening people traveling from Wuhan for flu-like symptoms. On Jan. 20 it is announced that the U.S. has its first case of coronavirus. A few days later travel from China is severely restricted. In mid-February the virus begins to spread in the Northeastern U.S., primarily from Europe.

March

On Mar. 1 our state of Rhode Island has its first two cases (linked to a school trip to Italy), and on Mar. 9 Governor Gina Raimondo declares a state of emergency. The elders of Christ RPC meet briefly during the first week of March and decide to alter the way we distribute the Lord’s supper in order to minimize handling of the elements (we celebrate the sacrament weekly, so this is an ongoing issue).

On Mar. 11 we advise the congregation to take precautions, including hygiene, avoiding crowds, and stocking up on some food and cold medicine. (A friend had nudged me to stock up for my family, and I’m glad I did. I knew that things were going to get interesting when Walmart ran out of hand sanitizer, and a stranger gave me a tip on where to buy some.) We postpone a church talent night and call for prayer and fasting on Friday, Mar. 13. That very day Gov. Raimondo orders that schools and nonessential businesses must close, and pleads with (but does not order) churches to do the same. Our elders hold an emergency meeting in the evening via FaceTime. In short order, the youth group (we cooperate with a local PCA church) and congregational meeting are canceled. On Mar. 15 we hold our first two online “services.” In the morning I preach on “Seven Ways to View a Crisis.”

The rest of March is a scramble to figure out a new normal. We know that business and travel will be curtailed, and church services strongly discouraged, until at least mid-April. Cases mount, and so does the death count. The first death is registered on Mar. 19. A month later the toll will be 187. Today we are over 1,000, mostly in Providence County. In little Rhode Island (1,500 square miles, the size of a county in most states), the virus spreads quickly. Thankfully the response of the government is vigorous and the populace takes it seriously, for the most part.

By the end of the month the schools “reopen” online. Our teenage son spends five hours a day in Zoom meetings. Strange fights break out, like the one between Gov. Raimondo and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, after Rhode Island State Police are ordered to stop cars with New York tags from entering the state. (This is then judged illegal and Raimondo has state troopers contacting New Yorkers and instructing them to quarantine where they are for 14 days instead.) It is entertaining to see two politicians, who a few months earlier would have argued against control of the United States border, arguing over who could travel between states.

The Howe family gets sick, almost certainly with coronavirus; but there’s no way to get a test unless you are a health professional or work in a “congregate living facility” (nursing home or other group home). One of our kids loses taste and smell, and three of them present with “Covid toes” (Google it). I am in bed for a week, sleeping, trying to breathe, eating colossal amounts of my wife Esther’s chicken soup and more vitamin C gummies than you would believe.

By the end of the month our congregation has 3-5 weekly evening Zoom meetings, for prayer or for sermon discussion. After conversations with other pastor friends, Associate Pastor Gabriel Wingfield (now pastoring Oswego, N.Y., RPC) and I get some perspective on what an online “service” is: it’s not really a worship service, but, like Paul’s Epistles, it can be a real communication of the Word and blessing to the church while we are apart. Like the Epistles, we begin our sermons with a greeting and end them with a benediction. We pray for the congregation’s needs and the world’s but guard privacy (since this is on the internet). Preaching from home isn’t great, but it’s a lot better than nothing (Rom. 1:11; 1 Thess. 3:6).

We grieve when we hear that our old friend and past chaplain at Geneva College, Rev. Tim Russell, dies of coronavirus in Memphis on Mar. 30.

April

We wash groceries. We research whether takeout food is okay (not just okay but encouraged, a bid to save the usually thriving Providence restaurant scene). Arguments, local and national, break out over who is an essential worker and who isn’t. Youth conferences are canceled, and Atlantic Presbytery is held online. Esther times grocery orders so that the InstaCart delivery person has the best chance of getting what we need. With governments unprepared and local retail crippled, Amazon, Target, and the internet in general are suddenly our best friends.

The need for PPE (personal protective equipment), especially masks, becomes dire. Early on I had tried to buy some N95 masks from a local work clothes shop, but they were gone. For a few weeks, the word from the government had been that masks were no use. This turned out to be disingenuous: the Surgeon General was trying to avoid a run on masks so that the few available would go to health care workers. But it didn’t matter. No one, whether health care workers, essential workers, or mere civilians, could get enough masks. I locate and spend $1,200 on hundreds of almost-as-good KN95 masks online: we don’t know if we’ll be able to get them again, we have vulnerable people in the congregation, and we have extended family in nursing homes in other states desperate for masks.

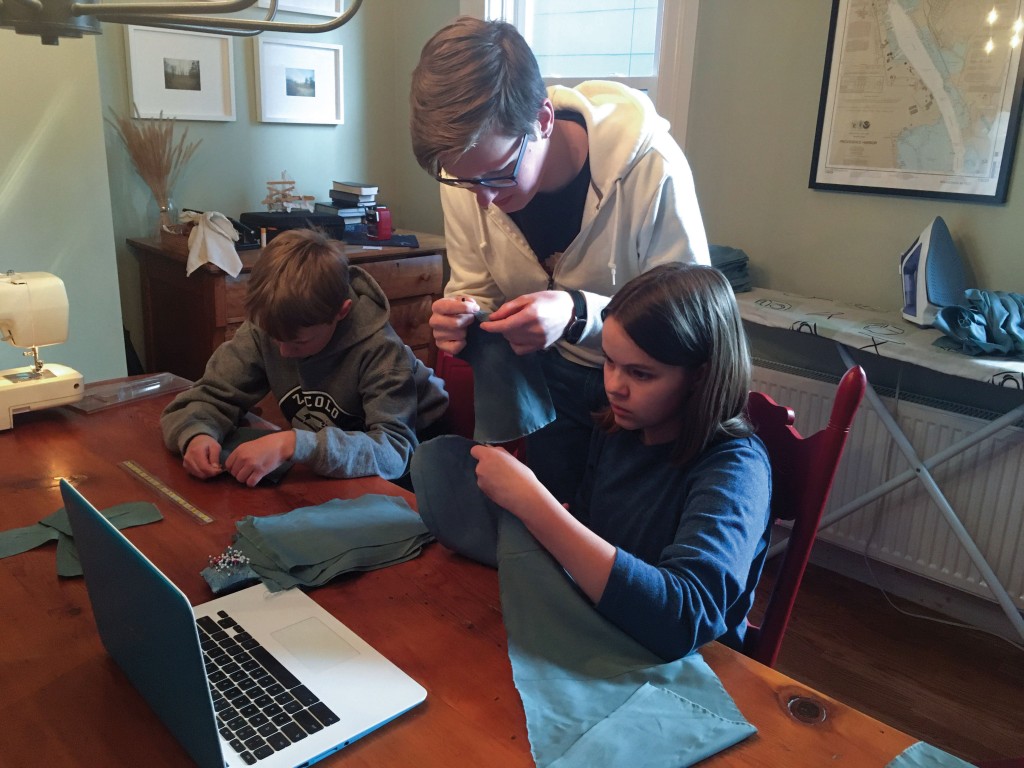

Boston surges. Massachusetts residents (a significant number of our church members) have to show paperwork when they come to Rhode Island for work. Husband and wife church members A. and F. are working in a hospital, cleaning, and in the laundry facility. We pray for them all the time. A bright spot. A friend coordinated a group of local women to sew masks, at the suggestion of an administrator in the local hospitals. Within a month a few dozen people (including Esther and our daughter Portia) have sewn over 10,000 masks for the local hospitals, mostly using dense-woven operating room sheets the hospitals provided. The internet was scoured for elastic and for grosgrain ribbon, since it makes a better material for ties. Never has a nearly forgotten skill been so precious.

Deacon Darte Bolton and his wife Kirsten drive around delivering masks and soup to church members. Elder Topper, who is being very cautious because he has only one kidney (he donated the other one), starts working out in my garage gym. Much more than I do. The garage gym gets better with the addition of a rower and a plyo box.

Another bright spot. Pharmacy giant CVS (headquartered in Woonsocket, R.I., an old textile mill town where French is the second language) develops a coronavirus test and begins offering it on a large scale, leading to a very high testing rate for the state late April–June. The state builds field hospitals, one in the convention center and one at Quonset Point, a former naval base. Slowly we move from panic over “the curve” to stability.

Gov. Raimondo, respected for her business sense before the crisis but not always liked, gains widespread kudos for her tireless handling of the pandemic. She holds a lengthy press conference every day for months. Commenting on teenagers ignoring the shutdown and congregating while out of school, she famously instructs them to “Knock it off!” An enterprising Providence shop starts printing “Knock It Off” shirts almost immediately.

May

The death toll remains high through the month. One member’s uncle dies in Washington, D.C., after briefly rallying and being taken off his ventilator. Another member’s father suffers through COVID-19 and seems to recover as well, but she is unable to visit him a half hour away in Massachusetts. A kind hospital chaplain speaks with her on the phone and assures her of Dad’s profession of faith. He is able to see his children on a video call, reconciling with his son, and meeting some of his grandchildren for the first time. He dies peacefully, alone, but not on a ventilator.

New cases decline markedly: the shutdown has been working. New York City starts to calm down as well: a huge relief. Nurses at the hospital where three of our children were born report that many, if not most, of the women delivering there in April and May were New Yorkers who had driven hours to have their babies in relative safety and calm. The nurses are terrified: they are being denied masks and other protective equipment.

Online worship services continue apace. Midweek Zoom prayer meetings are still well attended. Everyone knows someone who is sick (or knows someone who knows someone). Online class is now routine and, for our high school son, awful. We have subscriptions to four streaming video services (we’ve never had more than one). Physical education for the youngins is a lifesaver. Pastoral visits are phone calls or video meetings. So are session meetings. RPCNA Synod is canceled.

But there’s a sense that things are getting better, that we’re through the worst of it (or, remembering 1918-1919, that we’re through the worst of the first wave). The medical doctors in our church report that their hospitals have enough PPE. Exhausted mask-sewers get a break and sew extra for family and church members. I am able to send back most of my KN95 order. Cases are leveling off. Finally, Gov. Raimondo announces that the rules will lighten. Among those, church services can resume, under significant restriction:

• Masks must be worn during services.

• No books, offering plates, or other objects should be passed or shared.

• No singing.

• Hand sanitizer must be available.

• Indoor capacity limited to 25 percent of fire code.

• Lots of ventilation is recommended.

• If multiple services, high-touch objects must be sanitized in between.

We can do this. Our elders meet and adopt a plan, and our hardworking deacons jump on it. We plan for two identical services each Lord’s Day (enough to accommodate an average week’s attendance between them). A tithe box replaces the plates, and we sign up for an online giving option, for the first time. Every other row is cordoned off. Masks are required. We sing the week’s psalms, masked, outside, in the sun and breeze, before entering for the rest of the service. Our large windows are open as wide as their design and age will permit. The service is streamed for those too vulnerable or cautious to attend. One of our deacons builds a plexiglass “sneeze shield” for the pulpit so that the pastors don’t have to preach with masks on. He also builds clever wooden trays that hold communion elements at wide intervals, with wine and bread alike in cups, so that members can process forward and then sit down with them, remaining apart from each other.

We hold our first in-person services as soon as we are allowed, on May 31. In God’s providence this is Pastor Wingfield’s last Lord’s Day before leaving for Oswego RPC on Apr. 1. My son Kit was born in January and is not yet baptized. Gabriel baptizes him that day, and we receive a new communicant member, Andrew Kirk (interviewed by the session over Zoom during the shutdown), during the second service.

June

Deaths and new cases either remain the same or grow by less than 1 percent each day. As the state enters Reopening Phase II, we try to navigate the new new normal. Now hospitality is possible—but best done outside. Handshakes are all but history. Worship services are odd, but sweet. Much of the country seems to have a lull. Being in a part of the country where people go outdoors during the warm months, risks (from recirculated indoor air) are lower. Cases are starting to rise in air-conditioning country, but the deaths aren’t at a high level, and the national debate rages.

Meanwhile a different debate explodes, following the death of George Floyd on May 25. Riots break out in various cities. A protest is planned for downtown Providence on June 5. My son has resumed part-time work as a busboy at a local restaurant. When the protest violates curfew and marchers enter our neighborhood, pursued by law enforcement, he and I have an adventure getting home on foot, trying to dodge the protesters and being yelled at by the riot police. But in the end there is no violence (and we get home fine). Prayer and fasting again, this time as a presbytery.

The school year (a bust if there ever was one) officially comes to an end. We begin a summer of family debates about how to educate our kids next year. Almost miraculously, and so welcome after four months of nearly continuous time at home, we are able to take a vacation out of state for almost a week!

July–August

Late in June we are permitted to worship at 66 percent capacity, which means that finally we can worship together as an almost-whole congregation. Some individuals and couples have played it safe, and we understand why. Hospitality (sometimes even indoors) resumes. Many non-grocery, non-building supply stores have reopened. People have gathered for Fourth of July celebrations, often in groups far larger than permitted. Pent-up emotions are released not only in parties and troublemaking but in the loudest month, for fireworks, in at least 10 years. Every night sounds like Gettysburg. Finally, when it’s nearly the Fourth, our mayor starts a fireworks task force to crack down. Again, I am of two minds.

The revelry and the reopening may have taken their toll. Cases are starting to ramp up again, or so says our pediatrician. We pass our 1,000th death in mid-July.

As I write, my family is in quarantine, again, as we wait for results of our teenage son’s COVID-19 test. Maybe letting him continue to work in a restaurant wasn’t the best idea. It’s looking like a homeschooling-intensive school year. In some ways, it’s looking like another “lost year,” but we’re determined to make the best of it. By God’s grace it will be academically strong, if a bit lacking in friend time. By God’s grace we as a church will continue to figure out effective ways to connect with and care for one another.

Into the Future

By God’s grace we will look ahead into a future we can’t see, much less control. We are fragile, in our bodies and in our society. This is a moment of shame for the United States, and we should be in mourning. We pray constantly that the Lord would lift His hand from us and give us true repentance.

Big is fragile. One hundred churches of 100 members each are far, far stronger than one church of 10,000. The hundred churches will live, worship, and serve when the megachurch is long gone. Boundaries have meaning and purpose. The feuding governors have shown us that much.

Minimalism is silly. Our house at its height was a mess of cleaning supplies, sacks of rice, school materials, and hundreds of masks in varying stages of manufacture. Redundancy—food you can share, spare parts for the car, an extra heater in case the power goes out—is wise. Having just enough makes us entirely dependent on fragile supply chains and imperfect, fickle decision makers.

Those who rule don’t see all that far. If the wise men of Persia and Babylon couldn’t answer every question, why would ours? And the experts and advisors are the eyes of our governments. Many times have we sung, “Put no trust in earthly princes—mortal men who cannot save…” (Ps. 146). We treasure being Christians, a people who have survived and thrived through many plagues and pandemics. The horizon of our hope extends beyond what we see.

God is gracious toward those who humble themselves in His sight. We do not know how long we will have to do this. Maybe it will be over in six months, or maybe this low-grade chaos will be with us for decades. But God has sustained us thus far, and, by the grace of Christ, we know that He will continue to do so.