Tongue-Tied?

Lately I’ve ventured into textspeak. Instead of writing to my daughter, “I’ll see you at 5:00,” I sent her a text message that said something like “c u @ 5.” I cringe at the memory of my wicked syntax. It reminds me that language is a dicey business. It ever reinvents itself.

Along with merry old Oz’s melting wicked witch, we might moan, “Oh, what a world!” The problem is akin to what the nuns of Saltsburg sang of wayward Maria in The Sound of Music: “How do you solve a problem like Maria?/ How do you catch a cloud and pin it down?”

Language, like Maria, is elusive. But language can be pinned down. It tells us what we need to know. Sometimes our clarity falters, and sometimes we falter at others’ clarity. But without good success at our words, we’d fall into tongue-tied silence. Because of the eternal Word, our lesser words work.

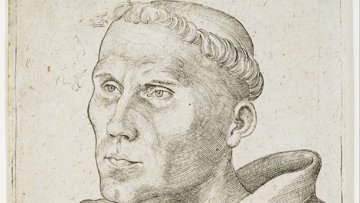

Luther’s Gift for Language

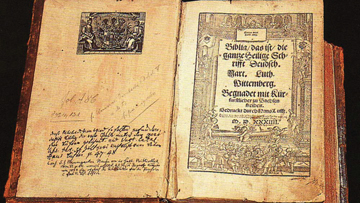

Martin Luther (1483–1546), the first Protestant Reformer, had a gift for language. His vigorous German translation of the Bible (1534) established a standard for the wild, wandering German language even greater than the effect the King James Version (KJV 1611) had upon the weird dialects of the English. It was Luther’s gift for language that helped purify Christian preaching, first for the churches of Europe, then for a great part of the world, down to our time.

Luther wasn’t always a good student of language. When invited by his boyhood teacher to recite his neglected Latin declensions, he declined the invitation. He was caned for his indifference.

Later, however, Luther proved to be a superb stylist. His last written words, found in a note on the desk beside his deathbed, contain this rhythmic witticism: Wir sein pettler; hoc est verum—“We are beggars; this is true.” The first three words are German, the last three are Latin, in matched syllabic meter.

Roots of the Luther Story

Many readers know that this lowly professor lit the match for that blessed explosion called the Protestant Reformation when he nailed the Ninety-five Theses to the castle-church door in Wittenberg. Some readers may even know the date: the Eve of All Saints, Oct. 31, 1517—500 years ago.

What is scarcely known, however, is the dynamo of biblical language leading up to that dynamite event of 1517. Let’s examine that dynamo.

Luther earned his doctorate in theology in 1512, gaining the high privilege of teaching sacred Scripture. He was appointed to an undistinguished college for monks in an undistinguished town in Saxony: Wittenberg. In those days—before the eye of the public and of certain suspicious authorities fell upon him—he lectured on the Psalms and on several Pauline epistles. Those epistles proved elusive; their gospel proved especially elusive.

To understand Luther’s trouble, we have to consider (at least) two Bibles. The first, likely enough, is the Bible Luther received—the Latin Bible on which he based his early lectures. The other Bible, oddly enough, is the Greek Bible of Constantinople—a city that fell 30 years before Luther was born.

The Bible Luther Received

The Latin Bible was the Vulgate, a translation revered in the medieval church as the standard for scriptural authority. The Vulgate was mainly the work of Jerome (c. 347–420 AD), dubbed vir trilinguis, “the man of three languages.”

In Jerome’s time, much of the Western world spoke Latin. Many of the Latin church’s pastors clamored for an improved translation of the Bible, one that could also unify the Latin-speaking churches; a common Bible. Trilingual Jerome, the man who knew Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, was chosen for the deed. His version became the “Common Bible”—the Biblia Vulgata. The Vulgate would reign over the Western church for more than 1,000 years.

Words, however, wither away (dost thou?) and some meanings morph (“now the birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise”?). So it was with some words and meanings in Jerome’s Vulgate.

Do Penance?

Matthew’s Gospel introduces the preaching of both John the Baptist and Jesus Christ in identical words: “Repent, for the Kingdom of Heaven has drawn near” (Matthew 3:2; 4:17). The Vulgate’s equivalent starts, Poenitentiam agite, a command that likely rendered Matthew’s Greek well enough in 400 AD: “Repent.”

However, by Luther’s time that meaning had meandered. Badly. People now thought it meant “do penance.” That is, “Go to a priest, confess your sins, and receive absolution.” Roman Catholics name penance one of their seven sacraments. But did Jesus Christ command penance? Clearly not.

The Other Bible: Constantinople and the Greek New Testament

In 1516 Luther got hold of a brand new book—a New Testament in Latin plus the original Greek on facing pages, published by Europe’s greatest scholar, Erasmus of Rotterdam (1447–1536). For five months the sheets for this theological bombshell were peeled off the city of Basel’s presses and bound in beautiful leather. It was an instant success: the first mass-market original language edition of the New Testament, produced by the minor miracle of moveable type.

How did Erasmus get hold of manuscripts of the New Testament in original Greek? We must thank the Ottoman Turks for that gift. For 700 years, successive Islamic empires had assaulted Constantinople, by land and by sea. By 1400 AD, this capital city of the Eastern Roman Empire had lost most of its territories to Islam. Now the Ottomans threatened to engulf this last bastion.

In hopes of shoring up their crumbling dominion, Constantinople’s insular leaders now sought alliances with the West. Western diplomats and churchmen journeyed to the faltering city, once the head of a mighty Christian empire. Precious Greek manuscripts began to trickle into the West, including manuscripts of New Testament books, for Greek was the language of Constantinople’s Bible.

In 1443, the Dominican monastery at Basel was bequeathed six such manuscripts. These not-so-ancient texts, dated to the 12th and 15th Centuries, proved nonetheless invaluable, for in 1453 that trickle of Greek dried up. Constantinople fell and Muslims ruled nearly all of Eastern Christendom. Six decades later, these Basel manuscripts, plus a few others, collated under Erasmus’s careful eye and would see the light of day in a printed book—March 1, 1516.

The Language of the Gospel

Luther, one of the few churchmen in the West to read Greek, eagerly snatched up this book from Basel. Its treasures were vast indeed. Among them was this gem:

Metanoeite: éggiken gàr he basileía tôn ouranôn.

Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has drawn near. (Matthew 4:17; cf. 3:2)

That’s the keynote sentence in Matthew’s presentation of Jesus’ preaching. As the Greek makes clear, Jesus spoke not of a Roman sacrament, but of a revolution in the innermost self: repentance—to mourn one’s sins for the sake of the love of God, to turn away from evil and toward God.

1517: Crisis in the Church’s Gospel

Repentance was the issue at stake the summer of the following year, 1517. Pope Leo X and a young and much-indebted archbishop, Albrecht of Brandenburg, schemed to raise church revenues by the sale of indulgences. An indulgence was a document bearing the Pope’s seal, promising the recipient relief from the punishments imposed in penance, and even from the unearthly sufferings of purgatory, the place where sinning Christian souls were said to go to purge away their evil.

Officially, these documents were gifts. Unofficially, few received an indulgence without paying the almsman. Brother Johan Tetzel, a Dominican friar, became the poster child for their sale. To advertise his wares, it seems he chanted this ditty in rhyming German:

So wie das Geld im Kasten klingt; die Seele aus dem Fegfeuer springt.

As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul out of purgatory springs.

Miffed by such greed, Luther’s prince banned their sale in Saxony. But that ban didn’t stop Brother Tetzel from setting up shop next door, just across the bridge from Wittenberg. And so our monkish professor of Bible penned his soon-famous protest, Luther’s Ninety-five Theses.

The Protestant Reformation thus began neither with its most famous doctrine, justification by faith alone, nor with faith alone’s companion, Scripture as the only infallible rule. Rather, it began with the gospel’s call to repentance. The first of these 95 blasts of Protestant protest posted on Oct. 31, 1517, is this:

“When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said ‘Repent’ (poenitentiam agite), he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.”

How did Luther come to discover Jesus’ true meaning—not “do penance,” but “repent”? He had studied that blessedly explosive Greek New Testament.

Luther’s Urgent Plea

As Luther knew well, we need truth in the Church’s language of the gospel. Our confidence in that truth relies in part upon the Church’s understanding of the languages of the Bible.

In 1524, Luther published an address to the city councils of the German realms, urging them to establish and maintain Christian schools and universities. These schools, he urged, must teach the Bible and the liberal arts. They must treasure and teach the languages of the Bible:

Let’s be clear on this: we are not likely to keep the gospel without the languages. The languages are the scabbard in which the sword of the Spirit is sheathed. They are the box in which this jewel is enshrined. They are the cask in which this drink is kept. They are the pantry in which this food is stored.…Hence, it is certain that where the languages do not remain, the gospel itself will ultimately perish.

Not all Christians can learn the Old Testament’s Hebrew and Aramaic, or the New Testament’s Greek. But some of us can. And of those who can, some of us must. The gospel depends upon it.