You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

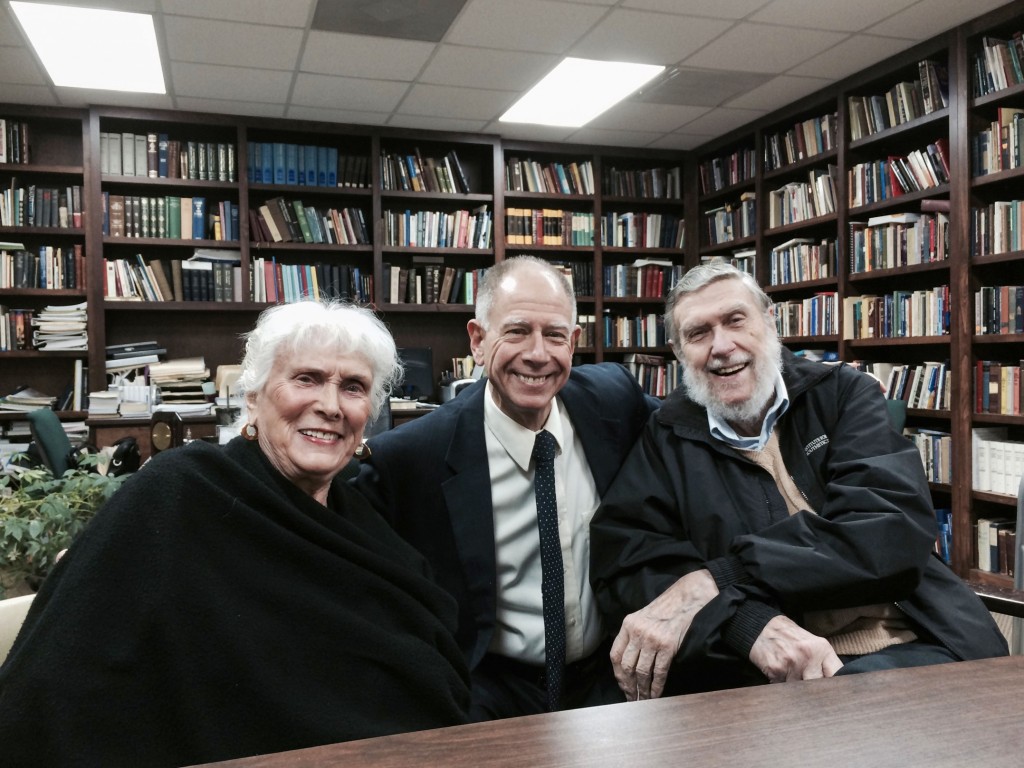

Pastor Jay E. Adams (1929–2020) spent most of his life in pastoral, teaching, and counseling ministries. He taught homiletics, counseling, and pastoral work at Westminster Seminary in Philadelphia, then taught at Westminster Seminary in Escondido, Calif. He founded the Christian Counseling and Educational Foundation and the Institute for Nouthetic Studies. Dr. Adams wrote over 100 books—including Competent to Counsel—in 16 languages and translated The Christian Counselor’s New Testament. He pastored congregations in the OPC and the ARP and the former RPCES and UPC. In 1992, he sat down with RP Witness editor Drew Gordon for this interview.

What convicted you to devote so much of your life to Christian counseling?

As a pastor in the early days I faced the problem of counseling people. Seminary had ill prepared me for any such help that I could give to people; so I began to study the question on my own. I found that all we had out there in the libraries was a group of books that, whether you were a Christian—liberal or conservative—or whether you were a non-Christian, presented exactly the same Freudian system. While I tried to use this to some extent, I was always uneasy about it, and never got any success with it. I even took a course for two semesters with a practicing psychiatrist at Temple University, attempting to learn a little more.

When I went to Westminster Seminary, I gained an impetus to do something more. I went to WTS to teach preaching, but, being the new kid on the block, I was given the course in pastoral work which had a unit of Christian counseling in it. Here I was faced with teaching something that I myself had not worked out thoroughly. Soon I realized that the existing systems that we were importing into the church from outside not only were inconsistent with Christian teaching, but also were doing harm and were unsuccessful. More and more as I began to use Scripture and Scripture alone, I began to see that God was blessing, that people were helped. Eventually we developed the system much more thoroughly and began a counseling center in conjunction with the teaching going on at Westminster.

You’ve called that kind of thing nouthetic counseling. Is that still the model you practice today, and could you define it for us?

There’s been no basic change. I don’t care what you call it, nouthetic counseling or not; nouthesia just happens to be a New Testament word used by Paul that deals with the question of counseling. I brought the word over to English for two reasons. First of all, we don’t have an English word that expresses the three elements of nouthesia. Secondly, the words counselors were using were freighted with all kinds of ideas that I wanted to avoid. Nouthetic counseling, according to the biblical word, is: First, a person has a problem and is confronted with that problem personally; secondly, he is confronted in order to bring about change through verbal means; and thirdly, it is for his benefit that this confrontation takes place.

In the Scriptures the word is often used as a familial term, in close, warm family relationship. The idea that confrontation means hitting people over the head with the Bible is not at all what we’re talking about; the idea is confronting the person in order to bless him and help him in his Christian life.

How would you say that this form of counseling contrasts with other models used by Christians?

The great contrast is that we have sought to do everything we can to develop a model from the Scriptures, growing out of exegesis and theological understanding as over against those who have developed their models using viewpoints outside of the Scriptures, developed by nonChristians. They baptized these unconverted into the Christian faith.

Are there things that we can use that are consistent with biblical truth from secular psychology?

There’s nothing necessary for us to integrate from outside. Otherwise, for 1900 years before Freud was born, the church would have been sitting around, twiddling its thumbs, unable to help anyone. All things necessary for life and godliness are found in the Scriptures. Problems that counselors are dealing with are problems with helping persons, and that’s what the Bible was designed to do. Jesus summed up the whole Bible as teaching love for God and for our neighbor; that is, how to deal with persons. And for that, the Bible is complete.

Having understood that, and also that our culture is a culture that despite all the deterioration that has taken place, and is still taking place, still retains some element of Christianity in it, there is no doubt that unbelievers have stumbled upon some of these things and used them in some warped and twisted ways. They have noticed some of them, and you might of course get something that way if you untwisted it. But all the pristine materials are in the Scriptures so you don’t really need to go outside the Scriptures to find the answers to how to help people.

You say there is a flood of emphasis on self in today’s world of psychology, and you see that as at gross odds with what the Bible says.

It’s an egregious error for the church to bring such teaching in from the outside. This Abraham Maslow-Alfred Adler emphasis has done a tremendous amount of harm and is continuing to do so. The Bible itself, of course, does not emphasis self, it emphasizes God, and it tells us to deny self. Some people want to find biblical support in the Scriptures, and they warp and twist the Scriptures in order to make them fit these unscriptural viewpoints. For instance, they say that since you should love your neighbor as yourself—there’s a command to love yourself! Indeed using Maslow’s ideas, they say until you learn to love yourself you can’t obey the other two commandments.

Now this is a terrible use of Scripture. First of all, they make three commands out of what Jesus called two: “on these two commands hang all the law and the prophets.” Secondly, there is no command to love yourself at all. Jesus was saying that you should love your neighbor in the way that you already love yourself; that we need to take some of that concern for ourselves and point it toward others.

Another example of how they twist Scripture in order to bring in these faulty, outside viewpoints is a misuse of the idea of the image of God in man. They say, “Look how important man was because he was created in God’s image. This shows us that we ought to be concerned with self and we ought to realize how much worth one has.” The self-esteem/self-worth movement focuses on those texts. But it’s not man whose worth is emphasized in the image of God in man, it’s God whose worth is emphasized.

If I have a photo of my wife and you tear that photo to pieces and spit on it and throw it on the ground and jump up and down on it, you’re in trouble with me. The reason is not that that paper is worth anything; the reason is because the person represented on it has been insulted. When a person attacks a human being, it’s not because of a human being’s value, it’s because of the One that he still reflects, even though dimly after the Fall, namely God, who has been attacked.

How then would you counsel someone who would be diagnosed, at least in worldly terms, as having low self esteem?

I would say that this is a false diagnosis, that the person has a very high self esteem and not low, and we can point this out. For example, people who are suicidal are claimed to have low self esteem. The fact of the matter is that they have such a high self esteem that they are saying, “The world shouldn’t treat me this way, I’m too good for this, I’m getting off the world.” They don’t care about what this does to family or anybody else.

You say that nouthetic confrontation aims at changing patterns of behavior to conform to biblical standards. How can this be done to assure that we don’t have hypocritical change?

First, we don’t counsel unbelievers; that’s the first and most important answer. You’re not supposed to counsel unbelievers because the Bible never commands it, and also makes it clear that it’s impossible to do so in any way that pleases God. Romans 8:8 says, “those who are in the flesh cannot please God,” so any change that takes place in an unbeliever’s life apart from regeneration and faith is a change displeasing to God. I’m not in the business of changing somebody to live in a way that is displeasing to God. What you do with unbelievers is evangelize them.

If an unbeliever comes in for counseling, we listen to what his problems might be, and say, “God has an answer for those problems, but the difficulty is that you are not in a position to receive that answer. The answer is on the other side of the wall; you are on this side of the wall. We’ve got to talk first about how to get you over there where the answers are. The way to get there is through the door, and the door is Jesus Christ.” So we evangelize. And we warn that you can’t use Christ simply as a means to the end of getting your problems solved. You have to be genuine about it.

The same is true for believers. Once a person has become a believer, he has to be exhorted not to do things simply in order to get what he wants, but in order to please God first. Whether he gets what he wants is secondary.

For example, a man whose wife has just left him may say, “I’ll do anything to get my wife back.” Now most people might think that’s great—he’s a highly motivated counselee. I’m always quite concerned when someone talks that way, so I’m likely to say to that person, “Well, would you lie, would you steal, would you commit adultery, would you murder to get your wife back?” And at that point he’ll say, “Well, you know what I mean.” And I say, “No, I don’t know what you mean, how far would you go in order to get your wife back? In other words, would you formally go through the motions or the actions of doing what Scripture has to say just to get your wife back, or—what would you do? If you do it that way, if she doesn’t come back, you’ll quit. If she does come back, you’ll quit, because you haven’t done it to please God. You’ve got to make the necessary changes that may or may not bring your wife back, but must make them in order to please God, whether your wife comes back or not. And if you do, in either instance, you’ll be in better shape to handle it.”

You’ve written that, in dealing with problems in relationships, people never understood the “why” more dearly than when the focus is on the “what.” Could you explain?

When you ask people, “Why did you do so-and-so?” that’s a pressured question. They’ll often grasp any old answer that they can quickly reach to get the pressure off: “Maybe I do this because I was dropped on my head when I was a kid.” There’s a place for a why-type question, but when you’re seeking data you want to ask what, where, when, how—the factual-type question. “Why” almost always leads to speculative answers rather than factual answers. Gathering data is better.

For example, when Jesus said, “What wilt thou have me to do?” that was a factual question. If you go through the Gospels you’ll notice every why-type question was not a factual or a factseeking question; it was a question to put pressure on people. He would say, “Why are you of so little faith?” Well, He wasn’t trying to find out why they were of such little faith. He was trying to get them to think about it, putting pressure on them to think seriously about their failures. That’s the distinction we’re making. If you get all the answers to what, where, when, and how, you’ll know the answer to why.

This form of counseling, as you say, gets to the point, and is to straighten people out and often saves months of counseling time.

It really is a function of sanctification—applying the Word to people so as to help them put off the old ways and put on the new ways that are pleasing to God.

Is there a danger that this message will simply enable a fledgling counselor to jump to conclusions without having love or respect for the counselee?

There are dangers in everything good. There are dangers in preaching, there are dangers in everything you do, but that doesn’t mean we stop doing the right thing. That’s one of the reasons why so many nouthetic books have been written, why so many conferences are held, why training is available, both on tape and in doctrinal programs, and in many locations, in order to keep people from misusing this approach.

Related to that, you say that this form can be used by any believer, really, at different levels. And, of course, certain laypeople would not have the training of others who would go to the training. How does this work out for laypeople in their everyday relationships?

Well, in Scripture we are commanded to counsel one another—all of us, not just pastors. Pastors do it as a life calling, but laymen are also called to counsel in an informal way. Galatians 6 talks about helping somebody who is caught in sin. It doesn’t say go get the pastor. It says you are to “restore” him, talking to the ordinary people in the Galatian church. Romans 14:15 and Colossians 3:16 talk about laymen counseling. Pastors ought to learn what to do, and they should train their people as best as possible. We all counsel; you can’t avoid counseling. The question is not whether you should do it or not, the question is how well you are going to do it. Parents counsel their children, friends counsel one another, husbands and wives counsel each other, etc.

What would you say are the greatest needs in churches today that your work addresses?

The greatest need in the church today that this work addresses is the exclusion of all the paganism that has been brought into the churches, and the adoption of biblical teaching in dealing with people’s problems. You know, developing your own understanding of people’s problems from the Scriptures, and developing methodologies that grow out of and are consistent with the Scriptures, is hard work. It’s much easier to go grab somebody else’s materials from elsewhere in a book, and adapt it to what you are doing. I think the church has just been lazy and has not done its job.

That’s what we have been trying to address. It’s hard work and it’s not complete. It’s going to take a lifetime of many people to develop a complete system. But at least what we’ve got works very well, many people have been blessed by it, and we are continuing to learn more all the time. You can’t put out fires in people’s lives, in churches, or elsewhere, by spraying gasoline on the fire. The very problems that are in our churches are the problems of paganism, and when you bring pagan thoughts and presuppositions and ideas and methodologies into the church, you’re only spraying gasoline on the fire.

Tell us about some of the changes you’ve seen in people and in churches since this kind of ministry for you began, and through the nouthetic model.

Anything that has ever walked, or crawled, or flown through the psychiatrist’s door has also come through ours. I get hundreds of letters every year from people who are grateful and thankful that they’ve been helped. And of course I’ve worked with hundreds of people myself, and am continuing to do so. You name it, we’ve dealt with it.

A number of people in the RPCNA have learned much from you. Have you learned anything from us?

In the early days when I was in much closer touch with the RPCNA I had some very fruitful times at Geneva College; I often spoke there and talked to many of the leaders of the church, including Jack White, who is a good friend. All those contacts have been invaluable. And especially in the early days when I was developing many of these things, I had many fruitful conversations with people there.

Is there anything else important that should be said about these things we’ve talked about?

I might say in reference to the layman, since that question arose—I think that it is of some importance that we help laymen—there’s a little book that I wrote called Ready to Restore, written from a layman’s viewpoint, that gives a lot of help on how to help your friends and family members.