You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

Historians sometimes underestimate missionaries or ignore their contributions to social justice and the advancement of Christ’s kingdom. That is the pattern behind the missing piece of the Indians’ story in American history.

The well-known side of the story is that white Americans sinfully stole the Indians’ land and unjustly forced them onto reservations.

The neglected story is how some white missionaries tried to do what was right in the Lord’s eyes and bring the gospel to American Indians, along with a new way of life.

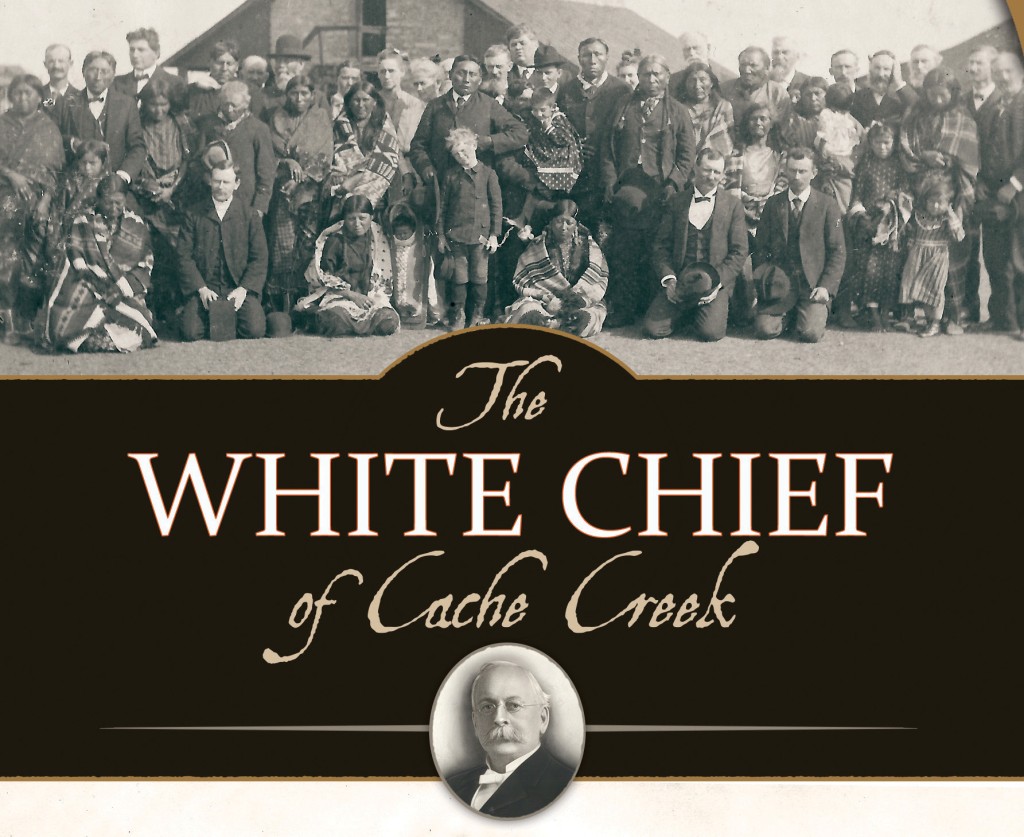

Faith Martin joined with the late Charles McBurney, a psalm-singing leader in the church, to record a key chapter of that history in a new book, The White Chief of Cache Creek. A school teacher and Reformed Presbyterian Home administrator by vocational background, Martin is also an excellent historian as she records the impressive record of the Reformed Presbyterian mission to Oklahoma Indians, 1889–1970.

She builds on earlier research by McBurney, who wrote his master’s thesis on the mission. She goes into detail about how William Work Carithers and his associates brought the gospel to several Indian tribes and tried to prepare them for a new civilization that would soon overtake them.

There were many obstacles in bringing the gospel and a new way of life to the Kiowa, Apache, and Comanche tribes in southwestern Oklahoma. The missionaries faced challenges from rattlesnakes, tarantulas, lizards, and coyotes, along with creek flooding, torrential rain, and malaria. The nearest post office was 20 miles away, and the nearest railroad was 90 miles away.

Sinful humans were also a problem. A researcher’s advantage is that Covenanters keep journals, write letters and magazine reports, and take minutes of meetings. Martin takes advantage of those documents, including more than 1,000 letters, and goes into vivid detail of the day-to-day challenges of this mission.

This story is not one spectacular victory after another, but small gains, as some Indians come to salvation and some fall away from faith in Christ. Others are attracted to a more entertaining style of worship in competing missions that have not embraced psalm singing without instruments. Pastor Carithers and his fellow missionaries had to respond to a very different culture.

If a man comes to salvation and has more than one wife, what should the church recommend? What about the use of peyote, a kind of drug commonly used by some of the tribes? Should premarital teenage pregnancy become a matter of church discipline? How should they train Indians for farming? Oklahoma farming is much harder than in Kansas or Iowa. How could they help the Indians become landowners before the state opens up to white settlers? How do you enforce Indian property rights against aggressive white cattlemen? Oklahoma was not yet a state and had few law-yers or courts to enforce property rights.

Mission work in Oklahoma in 1889 faced the challenges similar to overseas missions today. Different cultures clashed among Mexicans, Indians, white settlers, and missionaries.

For example, Tony Martinez, a Mexican, had been enslaved by Indians in his youth, swindled by a Mexican, then served as a scout for the U.S. Army. He settled in Oklahoma, marrying a Comanche woman. He came to salvation in Christ through the mission and married the woman living with him after his wife had died. He enrolled his two children in the mission school and was making progress in his faith. Then he was murdered by a Mexican cowhand who later escaped from prison and justice.

Martin gives tribute to the dedication and self-sacrifice of the Carithers family and many others who served short terms and lifetimes. Work Carithers was God’s man for this assignment. He had helped the mission board try to select the best person, and he wound up being voted into the job. “He walked as if he knew where he was going and talked without wasting words,” Martin writes. They built a multiracial church long before it became a popular idea among American evangelicals. Some white settlers became part of the RP fellowship. Mixed race families from Indian and white settler backgrounds also joined in the fellowship. Indians became ruling elders in the church and attended presbytery and Synod meetings, building friendships across deep cultural differences. “Cache Creek Mission was unique among the missions for actively encouraging white people and incorporating them into their fellowship,” she writes. “Indians and white people would worship together until the mission was closed in 1970.”

Missionary Anna Coleman captured that vision on her tombstone. After years of dedicated service in the ministry, she had asked to be buried in an Indian cemetery, and the Comanche tribal council approved. Her tombstone quoted Acts 17:26: “God hath made of one blood all nations of men.”

Another fascinating angle in this story is Faith Martin’s three-culture framework of analysis. She goes beyond a simple white–Indian conflict and identifies at least three cultures: white, Indian, and missionary. She shows the conflict between the Indian culture and its strengths and weaknesses, as well as the white culture. The white culture included theft of land, corruption of some government agents supervising the reservations, and oppressive sale of alcoholic beverages to the Indians. The Indian culture included polygamy, slavery, and drug abuse. The story illustrates the depths of human nobility and depravity.

The book shows a third culture among the missionaries. They attempted to treat Indians justly, to open doors to the gospel and a new way of life—of farming as a small business and way of supporting a family, and of dignity for women and education for children. The missionary culture was never perfect but can be distinguished from the pioneer white or Indian culture. These dedicated servants of the Lord offered a transcendent third way. “Carithers’s goal had been to get the Indians safely on the Jesus road before they had to walk the white man’s road. He believed that, once on the Jesus road, Indians would enter white culture from a position of strength. His belief in the strengthening power of Christianity was sorely tested as his congregation of new believers encountered the reality of the white man’s world,” Martin writes. “Indians quickly grasped there was a gap between the teachings of Christianity and its practice by most of the white people they would come to know.”

Some historians easily criticize the missionary efforts among Indians. Martin never indulges in that kind of chronological snobbery. She majors in facts and character description and helps the reader see the quiet heroism of those who embarked on this mission, in the spirit of the 1871 Covenanter confession of national sin against aboriginal natives.

Carithers had a noble and scriptural vision that was not fulfilled completely but made a better life for many. “His was a vision of peace and self-sufficiency for Indians following centuries of war-fare and misery,” she writes. “The first generation of converts would be farmers; their children could become shopkeepers, mechanics, teachers, doctors, and lawyers—like immigrants to America were doing, as his family had done.”

Carithers was joined by other dedicated RP servants of the Lord. Geneva College alums, Alice Carithers (Work’s sister) and Kate McBurney, gave the mission an unusual level of academic and educational excellence. Alice and Kate became circuit riding missionaries at times, visiting Indian camps only a few years after the tribes had been at war with the U.S. Army. The mission workers needed patience in working prayerfully through the hierarchical culture. A chief carried much influence spiritually and culturally and sometimes saw the Christian faith as a means to a better way of life.

“The road we point the Indian to is for him a long one, and in many respects, distasteful, so we need not wonder if our patience is sorely tried in our working and waiting,” Carithers wrote at one point. “But he who makes the seeds spring in their garden can make the richer seed take root in their hearts, and, after all why should we grow impatient, if we are sowing the seed with a loving and liberal hand. That is all that he asks us to do.”

Pastor Carithers, in some respects, was building on a vision that Baptist missionary Isaac McCoy had developed two generations earlier. McCoy and his wife had lived among Indian tribes in the Midwest, helping some to salvation in Christ, guiding some to farming, providing school for their children, and sharing a new life in Christ. McCoy became convinced that the Indians needed to es-cape white liquor traffic with their own state in what would be Kansas or Oklahoma. He hoped they could farm and have U.S. Senate and House representation. He found some support in Congress, but didn’t convince enough of the federal government of the justice of his grand vision.

The Cache Creek Mission was an attempt to fulfill McCoy’s vision in some ways. Before Oklahoma opened up fully to white settlement, the mission was helping Indians claim their land grants. White settlers sometimes cheated their way into ownership of Indian property. The mission also faced corruption within the Bureau of Indian Affairs, with some agents lining their pockets at the expense of Indians. Other government officials sought true justice for Indians, with Carithers sometimes lobbying the federal government on behalf of the Indians.

The Cache Creek Mission also faced the challenge of more difficult farming in Oklahoma. For the Indians, there were parts of white civilization that resembled Vanity Fair in Pilgrim’s Progress. Gambling, liquor, and other vices came with white settlers, who needed salvation just as much as the native Americans. Martin captures the detail of this side of the story very well, including Carithers’ sympathy for how the temperance movement led to state and national efforts to make the sale of alcoholic beverages illegal.

Other challenges were the need for Bible translations into three Indian languages, along with educating children who were learning at very different paces and needed as much individual attention as the missionary teachers could provide.

Another challenge was the natural Indian resentment toward white people. It took time to build trust. “As the missionaries became better acquainted with the Indians they were reminded that, to these proud people, white people were invaders,” she writes. “The Indians deeply resented having their conquerors also determine to change their way of life.”

The mission story was winding down at the end of World War II, as older Indians were going to be with the Lord, and many younger ones left the area for job opportunities. The RP Church nationally was going through its own challenges, making it harder to support the ministry. Mary Carithers had grown up as a daughter in the mission, and she and her husband, D.C. Ward, gave some of their best years to the ministry in the 1940s and 1950s. “His years at the mission were the happiest of his life,” Martin notes.

Faith Martin has written a key chapter in modern Reformed Presbyterian history, both in her con-tent and depth of research. She gives honor to whom it is due, and this work will be important for future generations.

Reformed Presbyterians don’t have “saints” because we are all saints in Christ. If we did have a museum of Christian heroes, this book would offer a record of many worthy nominees who pursued Christ’s kingdom in a very difficult mission field.