You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

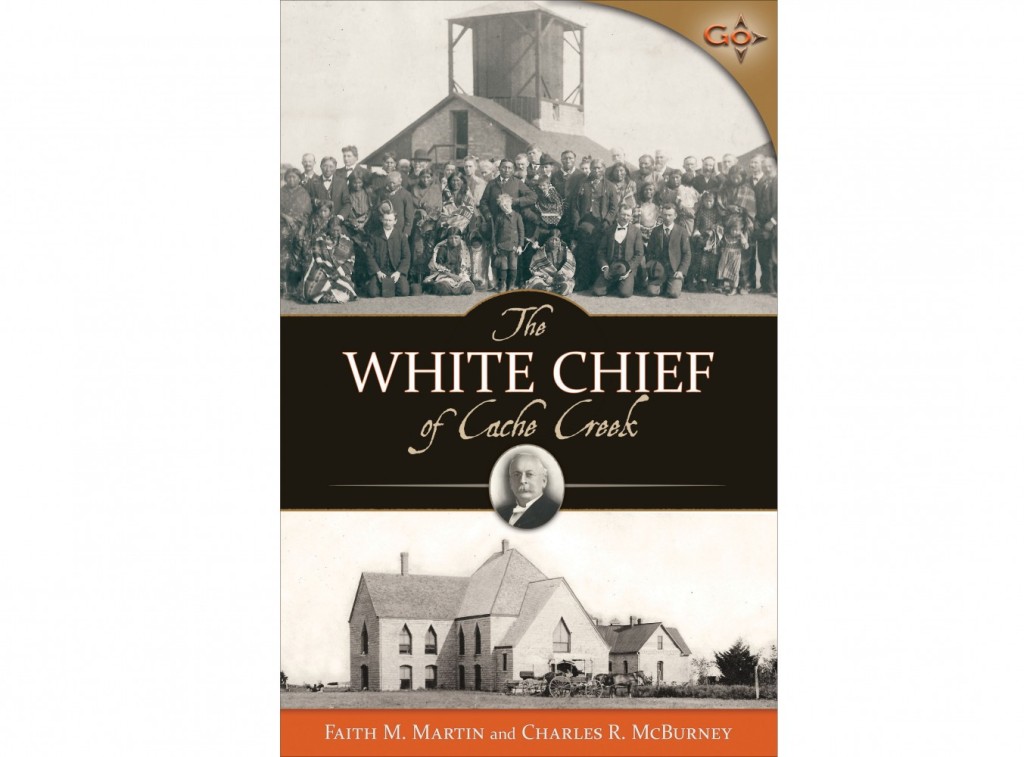

This article is an excerpt from the first chapter of the new book The White Chief of Cache Creek (Crown & Covenant, 2020).

The Wichita Mountains rise abruptly from the flat lands of southwestern Oklahoma. Those mountains and their surrounding plains were once the preserve of the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Indians, granted to them by the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867. The reservation was not large, just 4,639 square miles. Most of it was covered with tall grass and teeming with wildlife. Its wide open spaces were unfenced, broken only by clusters of pecan and walnut trees growing along the many streams that flow from the mountains. Nestled under the trees were numerous Indian camps holding the only legal inhabitants of the reservation.

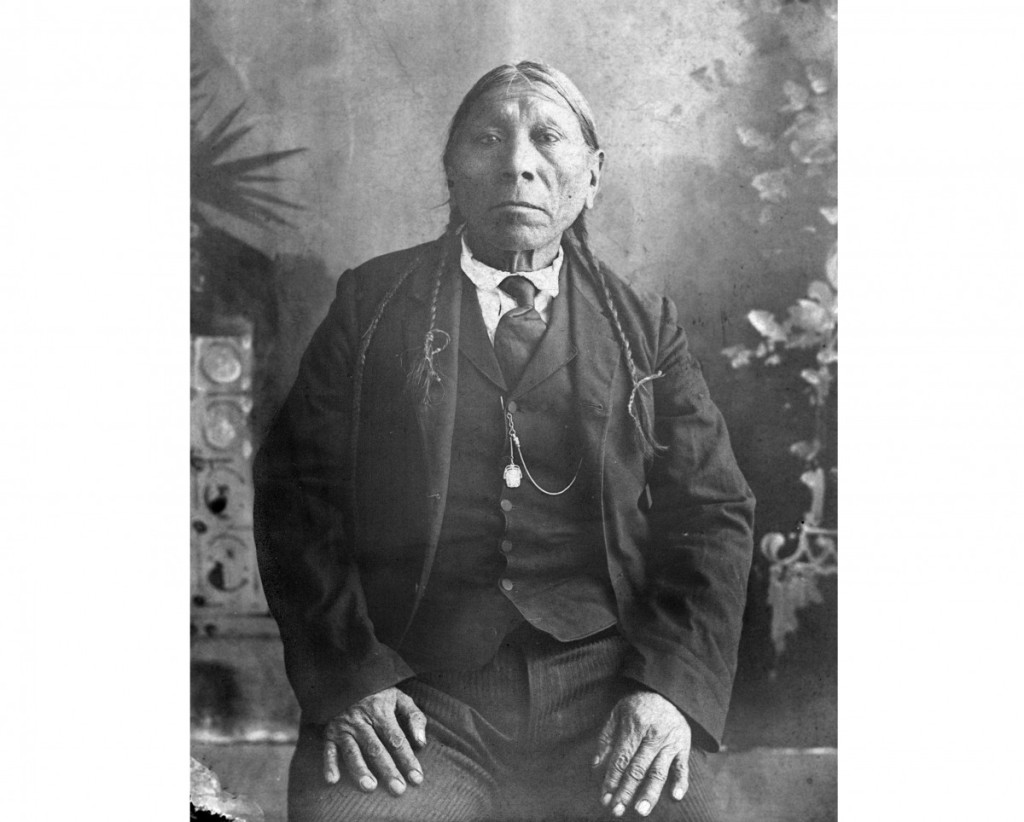

On a bright summer morning sometime around 1887, a Comanche chief of mature years left his camp and began a six-mile walk to the mountains. He had decided to walk as this would give him time to think about what he would say to the sun. Chief Attocknie enjoyed walking through the prairie grass. He loved this land with its open spaces and small trees leaning north, bent by the prevailing winds. His wife saw him go and knew he would not be back for several days because he had taken a blanket and tomahawk.

As Attocknie walked, he thought about the recent war with the white men in which some of his men had been killed. The Indians had fled to the top of a mountain, never suspecting the white men would camp all around its foot. There was no escape. He and his people admitted defeat. The white men said the Indians could no longer roam. They must stay on the reservation through summer and winter. There were to be houses, barns, fields, and wells. Attocknie did not understand it and was sad because his people had to live by the white man’s rules. As Attocknie reached the mountains, he began to think of what he would say to the sun. Surely the sun would see his trouble, his uncertainty. He must ask the sun for help.

Attocknie found a small cave on the east side of the mountain. It was just right. The bear had used it all winter and left its smell. The cave was empty now. Even the noisy snake that the white men called “rattler” was off sunning itself. Attocknie sat down, holding his tomahawk in case he needed it. He looked about for small plants with stems that he could break and suck to quench his thirst. He did not care about food. He had eaten nothing before starting out and would eat nothing till he returned to his tepee. One always fasted when talking to the sun. From the cave entrance he watched as the stars began to appear. He spread out his blanket and was soon asleep. He had decided what he would ask for.

In the morning, Attocknie sat up and watched for the sun to appear. He made himself comfortable, for he must pray from sunrise until noon. As the sun rose above the horizon, Attocknie began cutting himself, necessary for calling upon the sun. When he felt he had the sun’s attention, he began his prayer. He asked the sun to send a white man to teach his people white man’s talk, since they now must live at peace with the white man and the white man’s God. He prayed the same way for two more days. At noon of the third day he gathered up his blanket, took his tomahawk in hand, and went back to his family.1

It is not clear how much time elapsed, but eventually a young Covenanter minister would appear on the reservation and begin building a schoolhouse. Covenanters were radical Presbyterians who emigrated to America from Scotland in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In America they took the name Reformed Presbyterian and gained notoriety as ardent abolitionists. Their opposition to slavery was founded on principles derived from understanding Christianity as a gospel of grace. Alexander McLeod, their leading theologian, wrote:

In the system of grace, all men are represented as proceeding from one pair—as fallen from a state of integrity and happiness, into a situation that is sinful and miserable. God is revealed as beholding man in this condition with an eye of benevolence—having pity for the distressed, mercy for the miserable, and grace for the unworthy.…[T]he spirit of the gospel is love to God and to man, evidencing its existence by suitable exertions for the glory of our Creator and the happiness of all our brethren, here and hereafter.2

For Covenanters, “suitable exertions” meant action. God’s grace, the doctrine that had driven them to come to the aid of the slave, was now compelling them to reach out to Indians. “There is need for Covenanter radicalism in the settlement of the race and class problem. For one hundred years our church has stood as the champion of the equal rights of men…”3 were among the words used to stir the church into supporting a mission to the Indians.

Reformed Presbyterians shared with other denominations the hope of converting the Indians to Christianity, but they were unique in their skepticism of government plans for them. “It is a fact that cannot be readily explained, that those in authority at the head of this Nation, and almost everywhere throughout the Nation, legislate concerning the Indian as though they were actuated by malice, and not, as they should be, by a desire to ameliorate their hard lot and bring them into fraternal relations with the rest of mankind, not to say anything of a saving knowledge of Christ.”4

The Medicine Lodge Treaty had reserved portions of land for the exclusive use of the Plains Indians; however, in 1887 Congress passed the Dawes Severalty Act that broke those same reservations into individual allotments. Each Indian would be given a small plot. Once that was accomplished, white settlers would be allowed to take up the “excess” land and tribal rights to the reservations would be terminated.

Reformed Presbyterians read these plans and were outraged.

We have dealt with the Indians on the principle we would deal with a wolf. The Puritan method was to steal the Indian’s land and shoot him if he objected. The Dutch method was to buy Manhattan Island for $24 and then get the Indian to spend the money for drink. We have taken the remnants of the tribes we have not shot and confined them on reservations.…[The Indian agency has] allowed contractors to rob the Indian on one hand and the government on the other. It has refused to give them rakes and hoes, and has called them lazy because they wouldn’t farm.5

Government promises to assist Indians had proven empty. Indian agents were political appointees and infamously corrupt. Food, clothing, and tools that actually did reach the Indians were of poor quality. The education promised to their children was mostly absent.

Reformed Presbyterians saw the rapidly approaching end to the Medicine Lodge Treaty as a time of crisis for the Indians. Church representatives visited several reservations and decided to locate a mission near Fort Sill in Indian Territory. “The work is to be carried on among the Comanche Indians, a tribe characterized by noble traits. They number about sixteen hundred persons, so far as we can learn, no living voice has ever told them of Christ.”

Of all the Plains Indians, the Comanche had been the most powerful and the last conquered. Theirs was a stone-age culture on horseback, brutal and terrifying, but not without its exhilaration and graces. “Surely our responsibility to these people is great, in view of the wrongs done to them in the past, and in view of dangers that are threatening.”6 There was no doubt in the minds of the Reformed Presbyterians what that danger was. It was white civilization in its crudest form that would come flooding into the territory in a few short years. “Now is the opportunity before the country is inundated with whites, as it will be in a few years, and if these Indians are left in their present condition, they will be helpless amidst the whites.”7

As early as 1867, the women of the Pittsburgh congregations had organized a missionary society for the purpose of paying the salary of one missionary to the American Indians. The mission board called four men, but each in turn declined the appointment. (When a man was believed to be the right person for a position in the Reformed Presbyterian Church, a formal “call” was issued.) A special committee of the mission board reported that it had no one else to recommend. Would the project have to be abandoned? W. W. Carithers, a member of the committee, proposed that the board pray and then proceed without discussion to balloting until a missionary was chosen. Ballots were distributed, and Carithers, since he was the one who suggested the procedure, was asked to lead in prayer. As ballots were collected and unfolded, all but two had “Carithers” written on them.

Carithers’s full name was William Work Carithers. He was thirty-four years old, over six feet tall, and powerfully built. He walked as if he knew where he was going and talked without wasting words. In the days when “reverend” was considered a necessary part of any minister’s name, he was simply “Work.” Informal, warm, and friendly, even jolly, he ministered with concern and preached with conviction. In the five short years he was pastor of the Wilkinsburg8 congregation in western Pennsylvania, he had endeared himself to both young and old. One of the two who did not vote to send him to the Indians was the elder from Wilkinsburg. The other was Carithers himself.

Confronting his wife, Ella, with the news was not going to be easy. She was a favorite both in and out of her close family and numerous relatives. Slight and wiry, almost tiny beside towering Work, she was a bundle of energy. She was deeply involved in the lives of women in the Wilkinsburg community, a thriving middle-class neighborhood adjacent to the city of Pittsburgh. Leaving city friends for life as a pioneer missionary in faraway Indian Territory would be difficult, even frightening, for any woman, however committed she might be to serving the Lord. How would she react to the news? Work did not have long to wonder. She greeted him at the door with, “Why are you so pale?”

“They appointed us,” Work said simply. Ella’s response was prompt, almost casual. “When do we go?”9

That was December 18, 1888, and Mary, their only child, was three years old. The next day Work received a letter from the Reformed Presbyterian board of home missions, handwritten in ink, officially confirming his appointment as “Missionary to the Indians.” Carithers had been the corresponding secretary for the board during the long search for a missionary. It was he who wrote the letters of call and received the negative responses. Privately, he and Ella had discussed the proposed mission to the Indians and had agreed that if he were called, they would go.10 His own conscience, as well as the vote of his fellow board members, forced him to realize that he had no reason to decline the appointment. He would take the gospel to the Indians.

He would also show them how to farm the land on which they were confined. Reformed Presbyterians, like a large portion of Americans in that day, considered farming an honorable way to make a living. Work Carithers was no different. His vision was a settlement of Indian families with a church in the center. It would be the prairie version of the Old Testament prophecy: “They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks.…[E]veryone will sit under their own vine and under their own fig tree” (Mic. 4:3–4). His was a vision of peace and self-sufficiency for Indians following centuries of warfare and misery.

Faith Martin taught English in public schools before serving as executive director of the Reformed Presbyterian Home for 36 years. Charles McBurney spent the bulk of his career on the faculty and in the administration of Geneva College. He passed away in 2008 at the age of 93.

-

Attocknie never tired of telling this story when speaking about how he became a Christian. ↩︎

-

Alexander McLeod, Negro Slavery Unjustifiable, A Discourse, 1802, 16. ↩︎

-

R. J. George, “Opening Address to the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary,” Christian Nation, Sept. 26, 1900. ↩︎

-

Editorial, Christian Nation, Mar. 11, 1891. ↩︎

-

John W. Pritchard, Christian Nation, Apr. 15, 1891. ↩︎

-

J. K. McClurkin, Our Banner, Jan. 25, 1889. ↩︎

-

W. W. Carithers in a letter to the church. ↩︎

-

Wilkinsburg Reformed Presbyterian Church, Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania. ↩︎

-

Work’s concern about the call and Ella’s instant, positive response is not recorded but comes from the Carithers family oral tradition. ↩︎

-

Reformed Presbyterian and Covenanter, Mar. 1889. ↩︎