You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

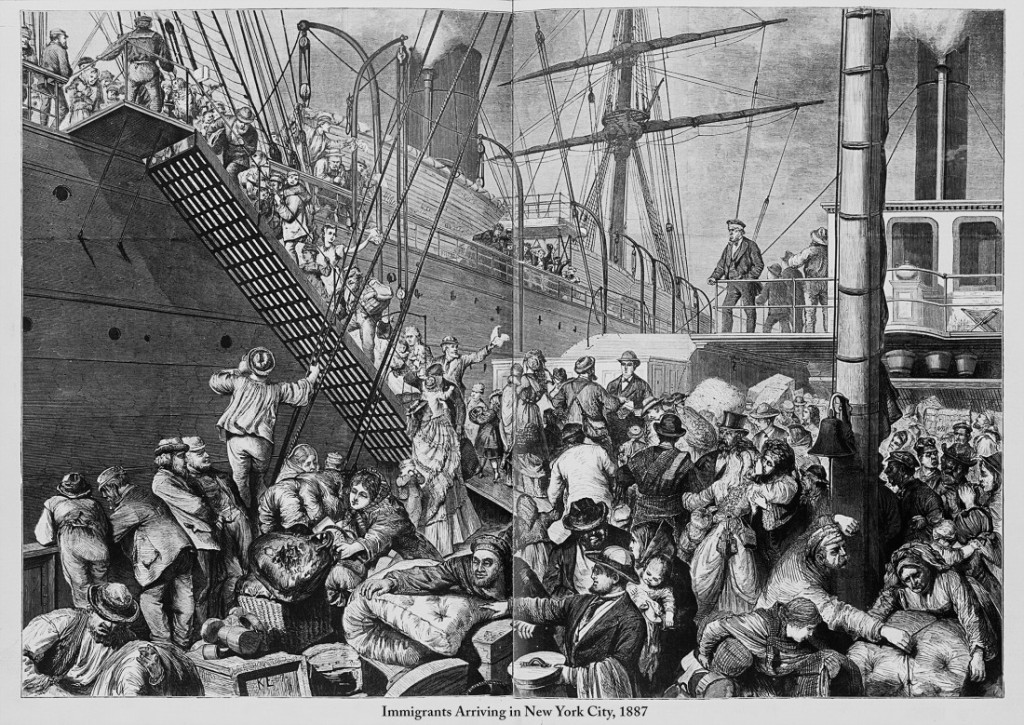

The history of the human race is a history of movement. God told Adam and Eve to be fruitful, multiply, and fill the earth (Gen. 1:28). Sometimes willingly, sometimes not; sometimes in obedience to God, and other times not, people have moved from locale to locale. If the detention was uninhabited, there was no conflict. If occupied, permission to settle could be sought and granted. If that did not go smoothly, sometimes war would break out. Regardless of the motivations and methods, the human race has covered the face of the earth. And so has conflict.

How ought Christians to think of this? We are God’s people, but a people gathered from every tribe, tongue, nation, and culture. We build our families, work our jobs, and live in our homes and communities, working for the good of the cities and towns in which we have been placed. When we find that our neighborhoods and schools, even our congregations, are changing due to a new population moving in, how are we to react? Where do our loyalties lie? From whom or what do we take our direction?

The answer is obvious—from God and the Word. While it ought not be seen as laying an exact blueprint for every question of immigration we must answer today, the Bible gives examples of God’s people as immigrants and receiving immigrants. Further, it teaches us what our attitudes ought to be toward those who become our neighbors.

Consider Abraham, a migrant at the command of the Lord. When he arrived at the land that would belong to his descendants, he was careful to conduct himself in an honorable and peaceful way with his neighbors. They reciprocated in kind. When conflicts arose, he and his sons submitted to God’s righteousness, even admitting when they had misjudged their neighbors and treated them wrongly.

Later, Abraham’s grandson Jacob and his sons would be migrants also, forced by famine out of the land that had been promised. They would live in Egypt, first as welcome guests, serving the Egyptians as shepherds and cattlemen, but in a few short generations as feared inhabitants, forced to suffer the weight of slavery, oppression, and even the murder of their children. In their suffering they cried out to God, and He remembered His promise to Abraham. He had prepared Moses for the task of leading His people into the Land of Promise and to take formal possession of it. Led by God, they served as His judgment upon a wicked people, and the land became theirs.

No longer migrants on this earth, God’s people had their home. How were they to treat those who were migrants like they once had been? “When a stranger sojourns with you in your land, you shall not do him wrong. You shall treat the stranger who sojourns with you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God” (Lev. 19:33–34 ESV). This is the starting point, but it does not say all that must be said.

According to James Hoffmeier, “The Hebrew word usually translated ‘stranger,’ ‘alien,’ or ‘sojourner,’ derives from the verb gwr….it means ‘to sojourn’ or ‘to dwell as a stranger, become a refugee’” (James. K Hoffmeier, The Immigration Crisis, Crossway Books: 2009, Kindle location 589). The difficulty comes in translation, as versions may differ in the English translation, sometimes rendering this as “stranger,” “sojourner,” “alien,” or “foreigner.” This last word is confusing, says Hoffmeier, because there are two Hebrew words more properly rendered in this way: nekhar and zar. This becomes confusing because gwr usually denotes one who has in effect legally become part of the community, while nekhar and zar refer to those who are temporary residents. While both groups are afforded certain rights, the gwr had the same rights (and responsibilities!) as the Israelite. The nekhar/zar had lesser rights (Hoffmeier, The Immigration Crisis, Kindle location 589–639).

When we read the Old Testament for guidance this must be kept before us—that there are different types of immigrants in the old economy. We must be careful to keep these distinctions in mind when we use the Old Testament to form our opinions on the matter. What can be simply said is that there was an expectation of humane and just treatment for those seeking to either become part of Israel or choosing merely to reside for a time with them.

The manifestation of God’s church in the world has also changed. In the times of the Old Testament, the church was Israel. It was only in and through the political nation of Israel that God could be known and worshiped. With the coming of Christ, that manifestation has changed. Now the church of God is no longer to be identified with one nation (or any nation). Rather, the people of God transcend all national and political boundaries. The church also is no longer contained within a particular people, but includes—and should seek out and embrace—all the peoples of the world.

While governments and politicians can and must argue over what a proper civil policy is with regard to immigration (and Christians ought to be engaged in that discussion), the issue for most of us is, How do we love those who live among us? This leads us to consider the importance of mercy and hospitality.

We must remember that we were once strangers and aliens before God (Eph. 2:12–19) because of our sin. Nonetheless, He chose to love us and welcome us into His family through Christ. Still, even alive by faith, we can rightly think of ourselves as Hebrews describes Abraham and his kin: “having acknowledged that they were strangers and exiles on the earth” (Heb. 11:13 ESV). Given the isolation and loneliness that we experienced as those under judgment, we ought to be able to welcome others in their physical and cultural homelessness with the welcome we have received from God.

We remember also the parable of the Good Samaritan. It was the rejected and outcast Samaritan who showed mercy to one robbed and beaten, one who had been passed over by those presumed to be responsible and caring but proving themselves to be otherwise. Which will we be?

Hebrews 13:1–3 directs us in this way: “Let brotherly love continue. Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares. Remember those who are in prison, as though in prison with them, and those who are mistreated, since you also are in the body.”

This is not merely something to strive for—it is something that needs to be done now. Our congregation in San Diego was visited in June 2013 by an Ethiopian couple and their two young children. They had fled Ethiopia after a massacre in 2003 that killed 500 of their tribe. They returned to church the next week with four more children and have been with us ever since. A few months later other relatives came to San Diego from the refugee camps in Kenya. Through them we have met seven other families. Most of them have worshiped with us for a time, with three of them joining. It remains an absolute joy and pleasure to be one with them—and other refugees—in Christ, sharing our lives together, encouraging one another in walking faithfully with the Lord. And we are not the only congregation to be blessed in this way!

While governments are charged by the Lord with executing justice and protecting those within their borders, the church is charged with evangelism. Evangelism is most effective when coupled with love and concern for the physical welfare of those to whom Christ is presented. It finds its fulfillment when all those who hear the good news of Christ join together in a common profession and common life together, learning to be one body together in Christ, each sharpening one another as iron sharpens iron, to glorify Christ for the salvation and peace that only He imagined and brings about. While governments rightly determine who may and who may not reside within their borders, Christians are to love and care for all those who are their neighbors, regardless of civil status, culture, or language. Our Lord Jesus Christ has done this. We are charged to do no less.

Mark England was ordained in 1993. He has ministered in the RPCNA since then and in San Diego since 2003. He describes himself as a Mexican-American Pennsylvania farm boy Reformed Presbyterian preacher.