“What are you working on lately, Byron?” asked my friend.

“Zwingli.”

“What?”

“Huldrych Zwingli.”

“Huldrych who?”

“Huldrych Zwingli. He was something like the first Reformed Presbyterian.”

“Oh! Never heard of him.”

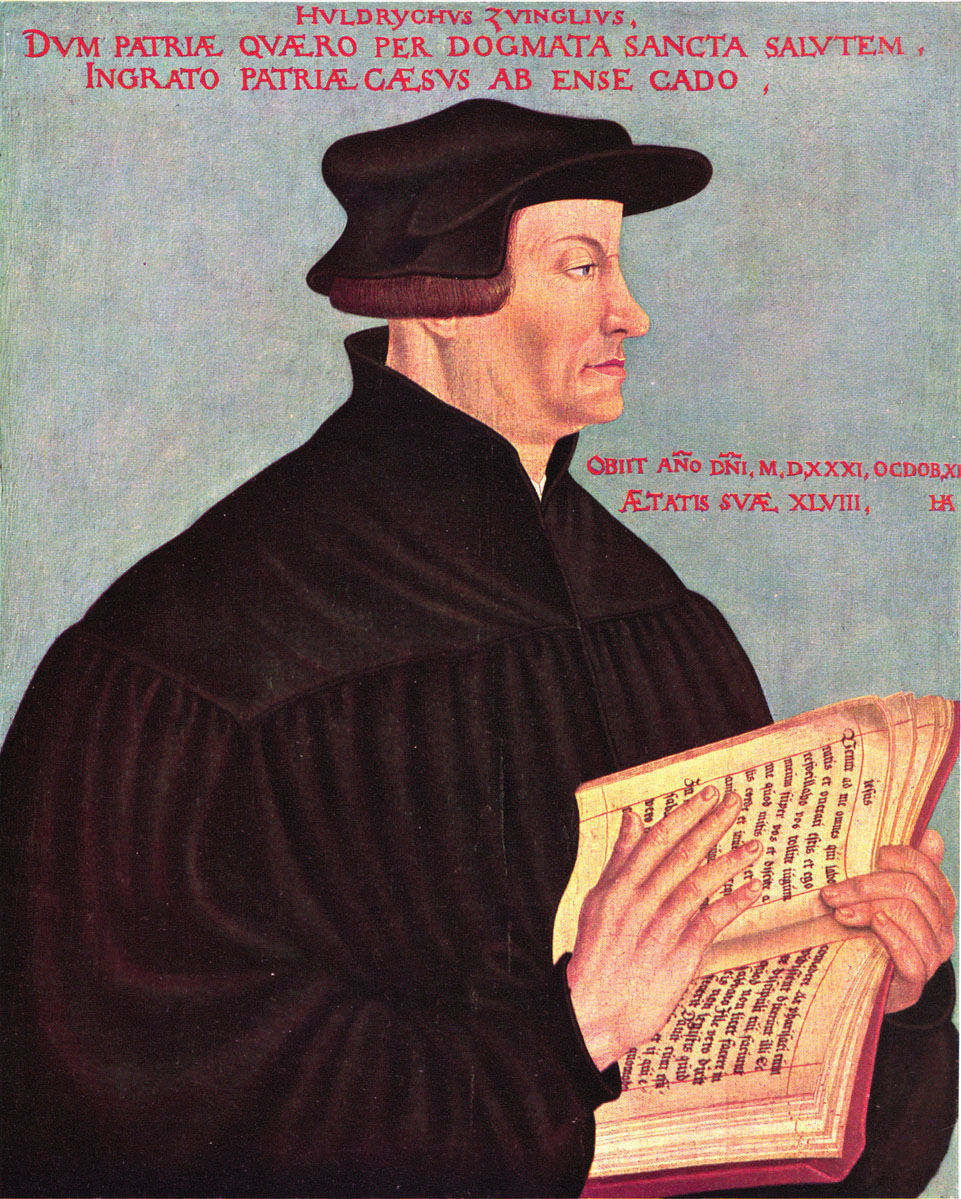

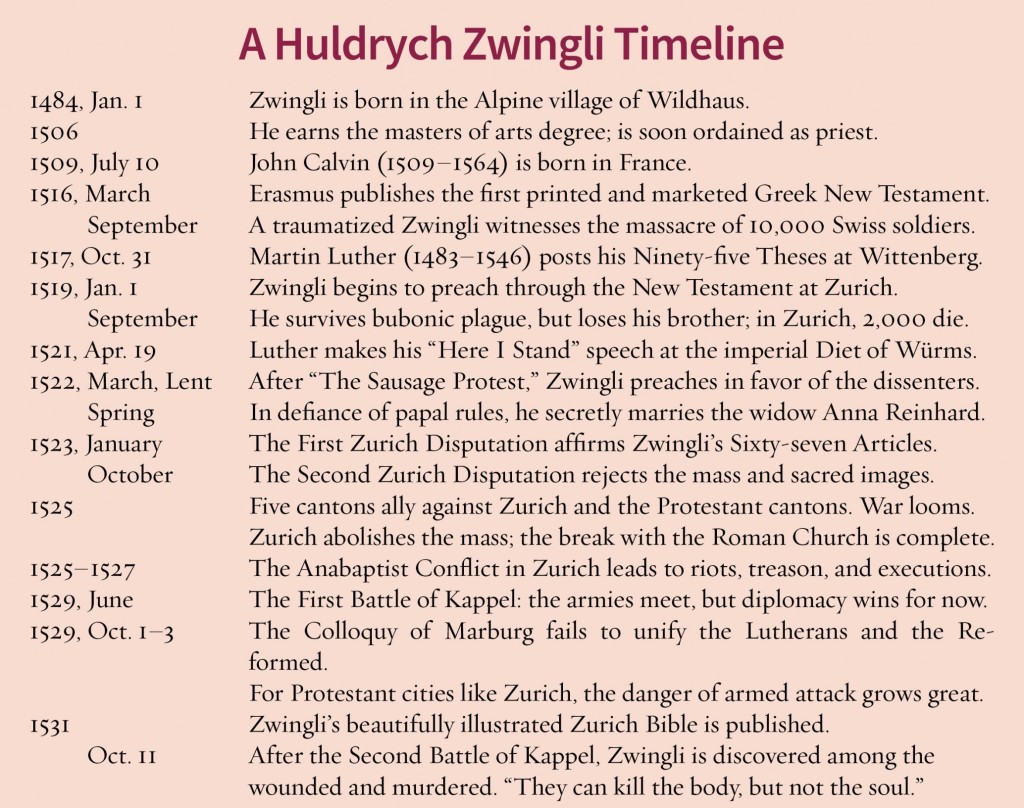

Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) is the greatest Reformer no one has heard of. He was indeed something like the first Reformed Presbyterian. The year 2019 marks 500 years since the start of what we now call the Reformed branch of the Protestant Reformation. Zwingli started that. Not John Calvin. Not John Knox. It was Huldrych Zwingli.

Of the truly great Reformers, those whose legacies embrace vast families of today’s churches worldwide, Zwingli is the least known. He rates but a single sentence in the Philosophers and Religious Leaders volume of Lives and Legacies: An Encyclopedia of People Who Changed the World(ed. Christian D. von Dehsen, Oryx Press, 1999). Likewise for ...