You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

Reformed Presbyterians are often taught to think kingdom.

The church, from its Scottish roots, has emphasized the doctrine of Christ’s kingship as complementary to His offices of prophet and priest. Scottish pastor William Symington spelled out the doctrine in greatest detail in Messiah the Prince (1839), which was republished in abbreviated form by J.K. Wall in 2014 (Crown & Covenant).

From a different angle, PCA pastor Charles Cotherman aims in a similar direction in To Think Christianly (InterVarsity, 2020), as he reviews post-World War II efforts to grow a Christian mind among believers. He traces a movement of loosely connected study centers that encouraged Christians to use their minds along with their hearts in the full service of Jesus Christ.

These people never formed a formal coalition, but Francis Schaeffer, R.C. Sproul, Jim Houston, and several others knew one another and consulted about how to help the average believer in the pew to know God and pay close attention to theology. In an age of growing secularism, they offered a new, yet old, idea: to think Christianly, to develop a Christian worldview or to develop the Christian Mind, to remember the title of a 1963 Harry Blamires book.

Cotherman’s subtitle is A History of L’Abri, Regent College, and the Christian Study Center Movement. He starts at Schaeffer’s L’Abri in the Swiss Alps, then flies to Regent College in Vancouver, and stops in with the Jesus movement at Berkeley, Calif. He also visits R.C. Sproul’s Ligonier Valley Study Center in western Pennsylvania, the C.S. Lewis Institute in Washington, D.C., and the Center for Christian Studies in Charlottesville, Va.

The personalities of these leaders were different. They would not have gone to the same church if they lived in the same city. Cotherman finds some important common ground among them, not so much in theology, though most were Reformed. What they shared was a zeal for the Lordship of Christ and a vision to pass it on to business leaders, mothers, writers, musicians, artists, athletes, and everyone else.

That Lordship vision is spelled out in kingdom theology, or the fact that Christ rules all of life. William Symington wrote about kingship in depth as Scotland engaged in the industrial revolution, while he was moving as a pastor from a rural church to a big city setting in Glasgow. Cotherman writes about key Christian thinkers who wanted to help believers bring the Bible to bear on all areas of life, just when the American culture was shifting from broad Judeo-Christian assumptions to more secular thinking.

L’Abri and Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer started the conversation for evangelical Christians in the 1950s. As a kind of low-key alternative to Billy Graham crusades, Schaeffer and his wife mixed hospitality with evangelism and answers to hard questions at L’Abri in Switzerland, and in later branches in Holland and England.

Schaeffer had come to faith by reading philosophy books in high school. He never went forward at a Billy Sunday rally. As an inquiring agnostic, he had figured he should be fair-minded and try the Bible along with Plato, Aristotle, Kant, and the other philosophers. His conclusion: “The strength of the Christian system—the acid test of it—is that everything fits under the apex of the existent, infinite-personal God, and it is the only system in the world where this is true. No other system has an apex under which everything fits. That is why I am a Christian and no longer an agnostic.”

He went on to read Reformed theology in the three volumes of Charles Hodge of Princeton Seminary, but he felt that the Dutch theologians like Abraham Kuyper were ahead of Americans in their presuppositional thinking, or questioning the premises of secular assumptions about how we know what we know.

Cotherman traces the rapid rise of L’Abri, which spread by word of mouth and by Schaeffer’s 1960s books defending Christian faith in the context of modern alternatives such as existentialism and relativism. Cotherman takes a helpful big-picture approach, in contrast to other, more detailed versions of the L’Abri story. The result is one of the best summaries of the Schaeffer life stories, showing the shift from fundamentalism to evangelicalism in his life.

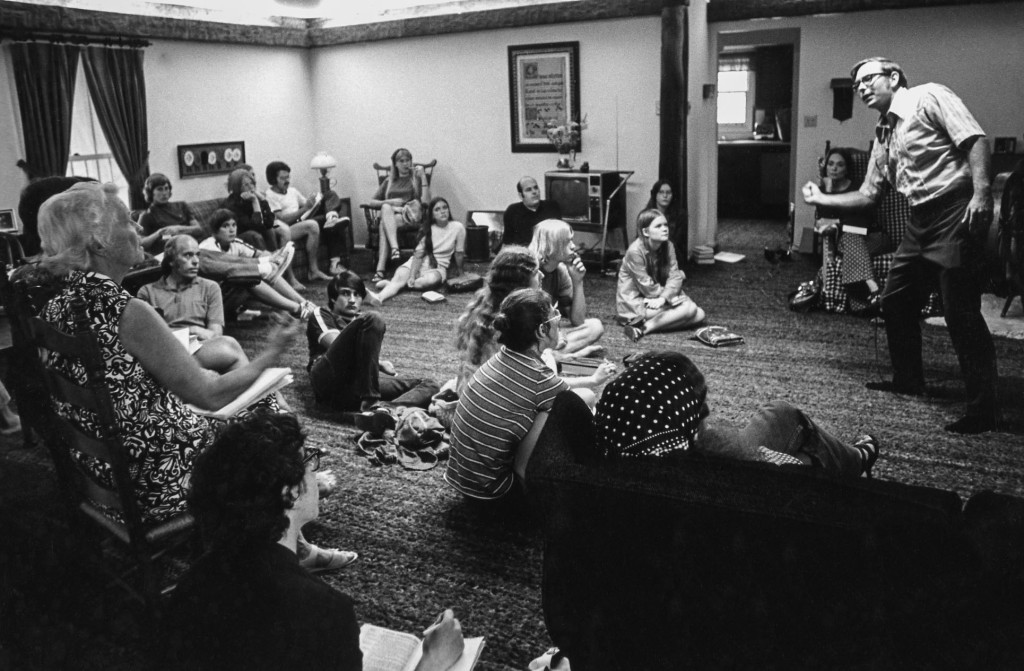

“Schaeffer invited a generation of evangelicals to engage their minds and the world with a scope as wide as creation and a confidence rooted in the trustworthiness of God,” he writes. Cotherman also reveals the challenge for Schaeffer and his family. They were building a ministry rooted in personal relationships and small-group conversations. Pretty quickly in the 1960s they were attracting big crowds of people who were fascinated by a very serious evangelical leader who could talk about painting, existentialism, abortion, and Hinduism, all under the Lordship of Christ.

Cotherman also offers insight into Schaeffer’s earlier years, when he had been a rising star in fundamentalist circles in the United States. Already a believer, Schaeffer went to Europe in his 30s, questioned the roots of his faith in Christ and came out stronger as an evangelical believer. Later Schaeffer wrote of that shift in his more personal book, True Spirituality. “Francis Schaeffer seemed well past his influential days,” he writes. Actually, Schaeffer was just coming into his years of even greater influence, the 1960s and 1970s.

Cotherman captures some keys to L’Abri’s lasting impact, including the true spirituality of both Francis and Edith Schaeffer. They really believed God is there and counted on Him to answer prayers. “Before he was frequenting museums, pontificating on Soren Kierkegaard, or functioning as an icon of countercultural evangelicalism, he was a pastor dedicated to aiding people in their journey toward the God who is there,” Cotherman writes.

Regent College and Jim Houston

Cotherman moves next to the rise of Regent College as a serious academic effort to give students a postgraduate course in Christian thinking, eventually becoming a master’s program in Vancouver, B.C. For some students it was the next stop in the 1970s after some months at L’Abri. Jim Houston also wound up collaborating with initiatives that became study centers instead of colleges—strategically located near large American universities, such as the University of Virginia and Berkeley—to help students learn to think Christianly or to take thoughts captive for Christ.

Regent and L’Abri were similar in the relational emphasis of both Houston and Schaeffer, along with a quest for academic excellence. Academically, the Regent challenge was bigger in the need to attract young scholars with doctorates in order to build a sustainable faculty, offer semester-long classes, and attract a student body. Houston had left the security of a prestigious Oxford appointment in England to take a step of faith in a new venture at Regent. He brought the Oxford tutorial method with him, spending personal time with many students. As higher education was moving in an impersonal direction, Houston swam upstream to make it more personal, approaching students with the heart of a pastor and the mind of a professor.

The Ligonier Valley Study Center and R.C. Sproul

Meanwhile a young R.C. Sproul was starting the Ligonier Valley Study Center in 1971 near Pittsburgh, Pa., recruited to the assignment by gospel patron Dora Hillman, a wealthy widow living near Pittsburgh. Sproul had learned from Schaeffer some of the ins and outs of L’Abri, as a model for the study center, with students living in homes with staff families.

Cotherman goes behind the scenes with good research in explaining how Sproul gained a vision for multiplying his audience to thousands of students with new tech video and audio resources. By the late 1970s, churches and families suddenly could have Sproul teaching them systematic theology and philosophy classes in living rooms and Sabbath School classrooms.

“Sproul arguably did as much as any popular evangelical preacher or media personality of his generation to bring theological education to the masses,” he notes. Sproul went on to become a key influence in the lives of former Nixon administration lawyer Charles Colson and other evangelical leaders.

The study center was influential in other ministries in the Pittsburgh region, as businessman Wayne Alderson brought union leaders out from Pittsburgh to help resolve labor-management tensions through Sproul’s teaching. Sproul eventually responded to the challenge of growth by ending his residential ministry and moving to Orlando, where Ligonier Ministries is still headquartered. He was the key player in what became a strong Calvinistic influence in the larger evangelical movement, as explained in Collin Hansen’s 2008 book, Young, Restless, Reformed.

On a personal note, I connected with the Reformed Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh through Sproul’s study center. I was studying to apply the Bible to news coverage and sat next to Steve Garber, who invited me to church. There Ken Smith preached on union with Christ and Galatians 2:20, and I met an aspiring young journalist named Lynne Hutmire, who would become Lynne Gordon.

New College Berkeley

Out in California, Cotherman traces New College Berkeley back to the Jesus movement, through believers who wanted to think Christianly. These people strove to be in the world but not of it, adapting to the 1960s West Coast counterculture, identifying in the early years as the Christian World Liberation Front. Sharon Gallagher visited L’Abri and read Schaeffer’s books, with a new excitement about faith and culture, having grown up in a more fundamentalist background. Journalist David Gill also appreciated Schaeffer’s thinking, writing to him at one point about setting up a L’Abri branch on the Berkeley campus, using an old fraternity house.

Most of these groups decided not to offer degrees and become accredited colleges, usually because of financial and credentialing challenges. None of these groups found magic formulas for the balance between study, hospitality, evangelism, discipleship, and academic excellence. They did have two solid models in Regent College, with Jim Houston’s desire to invade the university world on its own terms; and L’Abri, with Francis Schaeffer’s informal approach to helping young people think Christianly.

The University of Virginia

At the University of Virginia, Cotherman tells how Beat Steiner developed the Center for Christian Studies, with advice from Jim Houston and Francis Schaeffer. Strengthening the UVA venture was an informal partnership with Trinity Presbyterian Church (PCA) and pastor Skip Ryan, who had spent six months at L’Abri. Cotherman captures the vital importance of the church support, when most of the other ventures did not have such a strong local church connection.

In that chapter Cotherman shines in storytelling, as he traces the center’s origins back to a providential meeting between campus minister Daryl Richman and student Bob Bissell. Lifting weights in the gym, Richman shared his faith with Bissell, whose friends started gathering for small-group fellowship. Eventually that gym connection would indirectly help the university become a hub for all kinds of evangelical initiatives, including the study center. Providentially, a building became available for the center at just the right time. At another point the writings of the university founder Thomas Jefferson were important in persuading the university to not discriminate against Christian ministry on campus.

C.S. Lewis Institute

In Washington, Jim Houston originally linked up with former pro-golfer Jim Hiskey at the University of Maryland, in what eventually became the C.S. Lewis Institute. Hiskey and his wife had spent several months at L’Abri. Cotherman wisely emphasizes personalities and friendships among all these people. Schaeffer, Houston, Sproul, and Hiskey all knew each other, as part of a network of evangelical Christians. Cotherman’s constant references to who knew who and when and how is a big asset of the book, with plenty of footnotes about letters and interviews. In many respects Cotherman mixes the skills of an excellent news reporter with the benefits of academic research, along with a keen grasp of the relationship emphasis underlying all these ministries. Very few historians have been able to bring all these gifts to the history of the evangelical movement since World War II.

As Cotherman shows in his book, these people and their organizations didn’t have bylaws to share or formulas to follow. Schaeffer and Houston were relationally oriented believers who would never come up with a five-step plan to invade the secular university or grow the Christian mind.

Some of the centers did join what is now called the Consortium of Christian Study Centers. But Cotherman’s story reveals how the pioneers, such as Schaeffer, Houston, and Sproul, knew each other, met here and there, and corresponded by letter, long before email and Zoom. They launched a growing band of brothers and sisters who pioneered to help thousands of Christians to love the Lord with all of the mind as well as the heart.

Russ Pulliam directs the Pulliam Fellowship program for The Indianapolis Star and Arizona Republic. He has been a reporter for the Associated Press in New York City and the Washington Post. He is the author of Publisher: Gene Pulliam, Last of the Newspaper Titans, a biography of the founder of the fellowship. Russ and his wife, Ruth, are members of Second (Indianapolis, Ind.) RPC. They homeschooled their 6 children and now have 16 grandchildren. A daughter, Sarah Pulliam Bailey, reports for the Washington Post, and her husband, Jason Bailey, works at the New York Times.