You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

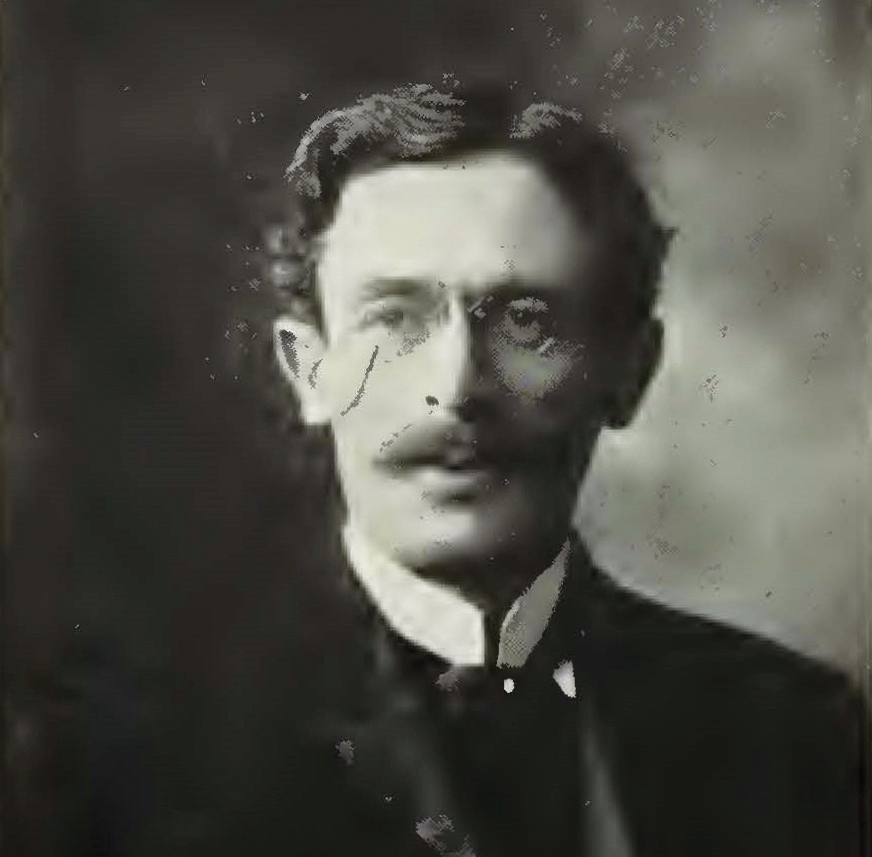

Born Aug. 30, 1862, in Crivitz, Germany, to Jewish parents, Louis Meyer would eventually become a minister of the gospel in the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America (RPCNA). Before his conversion to Christ, he studied medicine and became a surgeon, but an infection led him to put that profession on hiatus while he spent four years traveling the world by sea, working as a steward, and then as a chief purser on steamships, in the interests of improving his own health.

After his recovery, he immigrated to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he intended to resume his medical practice. In the providence of God, he was deeply affected by a sermon series on “Christ in the Book of Leviticus” by Rev. J. C. Smith. Not only was Meyer enabled to behold Christ in the Old Testament by faith, Meyer also came to be married to J. C. Smith’s daughter.

As Franz Delitzsch has aptly stated, “We are all Japhethites dwelling in the tents of Shem” (C. F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament: The Pentateuch, 1885). J. G. Vos has expounded upon the Jewish roots of Christian worship in his tract Ashamed of the Tents of Shem? The Semitic Roots of Christian Worship. The Psalms sung in the worship of J. C. Smith’s congregation were also very influential in the conversion of Louis Meyer. He would go on to study theology at the RPCNA seminary in Allegheny, Pa., and then to minister to predominately Gentile RPCNA congregations in Minnesota and Iowa; but he always had a heart—as did the Apostle Paul (Rom. 10:1)—for the salvation of the Jews.

He was also appointed, in 1900, to serve on the Board of Home Missions for the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. He lectured nationally and internationally on Jewish missions and contributed often to periodicals such as The Jewish Era, The Chicago Hebrew Mission, Christian Nation, Glory of Israel, Zion’s Freund, and The Missionary Review of the World (he became an associate editor of the latter, and he also served as an editor for The Jewish Missionary News). Additionally, he served as an editor to the series of articles that would be published under the name The Fundamentals.

Meyer once gave a series of lectures at McCosh Hall, Princeton Theological Seminary, in February 1911. A portion of his account of that event is given here to offer a sense of the man and his mission:

“None of us had any idea whether any of the students would attend. We counted upon a number of those from the Theological Seminary, who know me, and upon some of the people of Princeton, but all of us agreed that McCosh Hall, which seats 600 people, would prove rather large for the occasion. Thus the hour for the meeting came, and lo, there were less than fifty chairs vacant in the hall, and a large crowd of students had appeared. Our harpist and our singer, two good Christian ladies, proved a success, and their earnest music was well received. Then I was introduced. I commenced with a broad history of the Jews, past and present, speaking about twenty minutes without revealing my real purpose, and the audience followed me with interest. Suddenly I closed my narrative, and I went on somewhat like this: “Jewish History is true. It is recorded in the Old Testament. The Old Testament was closed at least 2,500 years ago. Whence did its writers get the knowledge of such history which is peculiar and extraordinary? By divine inspiration. Then the Old Testament is the Voice of God.” While I was developing these thoughts, some of the students who had been lolling in their seats, sat up and leaning forward, began to show signs of special interest.

“Then once more I turned to Jewish history and asked the question, “What does it teach us?” My answer was, “It teaches us that the master sin of men is the rejection of the Lord Jesus Christ.” It began to grow very still as I was thus appealing to every one present. Just as I closed the appeal and was ready to finish, the great bell of the university struck nine, and every one of the strokes was clearly heard amid the stillness. It was like the call of the Lord. It was of His ordering, for I had not known of the existence of the clock. Deeply stirred myself, I was silent while the clock was striking. When it had ceased, I simply said, Amen. For a little all was silence. Then two students arose, and, as their fashion is, showed their approval by applause, and in a moment the hall resounded with the clapping of hands, the Christian men and women, the professors and the preachers present joining in it. But I sat down, not even acknowledging the applause, because the praise belonged unto the Lord.”

His contributions to the causes of educating Gentiles and calling the Jews to believe in Jesus as the Messiah promised in the Old Testament were many. At the time of his death in 1913 at age 50, he was working on a project to highlight the lives of notable Jewish Christians during the previous century. Twenty-one such biographical sketches by him were published in 1983 under the title Louis Meyer’s Eminent Hebrew Christians of the Nineteenth Century: Brief Biographical Sketches. It was on a trip to California that illness overtook Louis Meyer. His biographer, Mrs. T. C. Rounds, writes of his final days:

“Though for three weeks he had been blind, with great self-control he concealed the fact from his wife, who was constantly by his bedside, lest it should distress her.

“As he neared the heavenly shore his face lit up as with a beatific vision. His blinded eyes, now open, evidently caught the face of his Saviour, for he whispered “Christ” —then later, “Pa.” (This was his father-in-law, who had led him to Christ.) It was beautiful that he should see his Saviour first, then he who had led him to Christ.”

A German-born Jewish Covenanter minister of the gospel is not a juxtaposition of words that one sees every day, but Louis Meyer was an extraordinary Christian worthy of remembrance. His passion for bringing the gospel to Jews serves as an inspiring example that God has not forsaken His “chosen people” but has a plan to ingraft them again into His Church. Samuel Rutherford, the Scottish Covenanter, once wrote:

“O to see the sight, next to Christ’s coming in the clouds, the most joyful! Our elder brethren the Jews and Christ fall upon one another’s neck and kiss each other! They have been long asunder; they will be kind to one another when they meet. O Day! O longed for and lovely day dawn! O sweet Jesus, let me see that sight which will be as life from the dead, Thee and Thy ancient people in mutual embraces” (Letters of Samuel Rutherford, 89, Andrew Bonar’s 1863 ed.).

That vision was shared by Louis Meyer, and many who pray earnestly for the salvation of the Jewish people, according to the promises of God. Writing of his conversion, Mrs. Rounds leaves us with a rich summary of Meyer’s witness to the gospel of Jesus Christ:

“His conversion, therefore, should be an encouragement to every faithful preacher of the Gospel, proving that…the Gospel is still ‘the power of God unto salvation to every one that believeth, to the Jew first, and also to the Greek.’”