You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

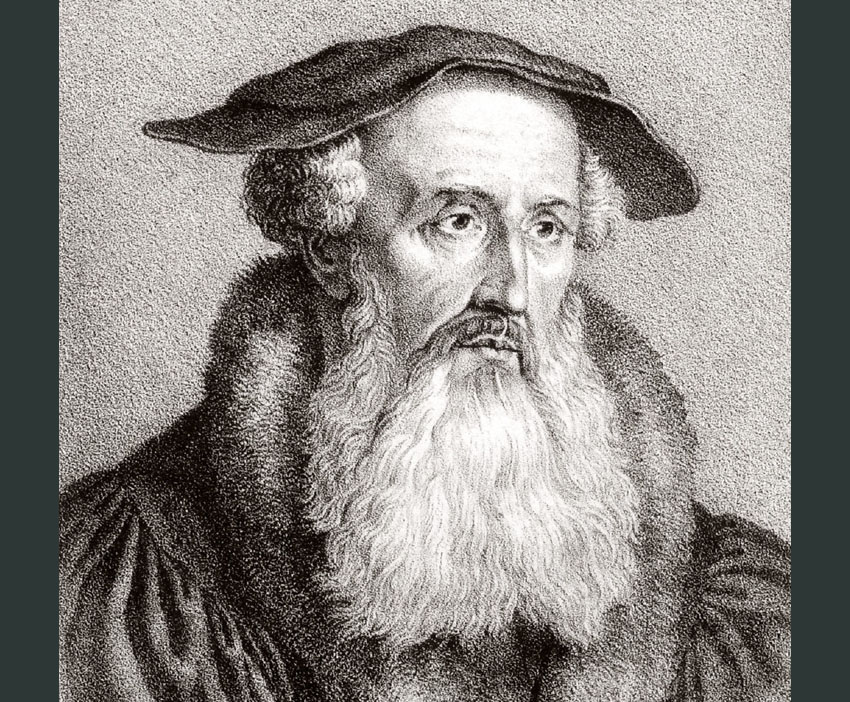

The name of the second-generation Swiss Reformer Henry Bullinger (Zwingli’s successor in Zurich) is not nearly as well known today as that of Martin Luther or John Calvin. This was not always the case, nor should it be so today. Bullinger was converted 10 years before Calvin and died 12 years after him. He enjoyed an international reputation greater than that of either Luther or Calvin, as the 12,000 letters to and from him testify. He was a personal friend and advisor of many of the leaders of the Reformation. He corresponded with Reformed, Anglican, Lutheran, and Baptist theologians. He corresponded with Henry VIII, Lady Jane Grey, Elizabeth I of England, Christian II of Denmark, Philipp I of Hesse, and Frederick III, Elector Palatine. One scholar’s description of him as “a spider at the centre of the web of the Reformation” may sound vaguely unflattering, but it bears witness to the undisputed effect of his influence. He was called in his day “the common shepherd of all the Christian churches,” and, by more recent writers, “the father of the Reformed Church.”

Bullinger’s literary output was prolific; his 127 works amounted to more than Calvin and Luther combined. The quality of his writing was consistently high. He was responsible for the Second Helvetic Confession, the most widely accepted of all the 16th-Century Reformed confessions. In the opinion of George Ella, “Seldom has there been such a great man who made so few mistakes.” His work is more balanced than Luther’s or Calvin’s. Ella continues, “Luther often has an aggressive, intolerant faith.…Calvin’s works…prove at times to be too defensive…philosophical and legal” (I.xi). Bullinger worked along with Calvin and Farel to come to a more balanced understanding of the Lord’s supper, resulting in what was called the Consensus Tigurensis between Zurich and Geneva in 1549.

Of all that Bullinger wrote, however, his Decades were most influential: five sets of ten sermons (a “decade”) each, dealing with all the main topics of systematic theology. Preeminently this was a book written by a preacher for preachers. Bullinger’s goal was to present Reformation theology in a readable form to help pastors with little theological training in their sermon preparation. The teaching contained in the Decades was the result of many years of reflection and teaching (in contrast to Calvin’s Institutes, which were revised numerous times as his thinking developed; indeed, Calvin’s 1550 edition of the Institutes shows his dependence on Bullinger’s Decades). The Decades became an instant bestseller, becoming more popular than Calvin’s Institutes in England. In 1586, the Archbishop of Canterbury instructed junior clergy and aspiring preachers to use the Decades as a textbook.

The Decades begins with a preface dealing with the creeds of the church, showing how Reformation theology is directly related to the original apostolic teaching (a recurring theme in Bullinger’s writings), over against the claims of Roman Catholicism that the Reformation was an innovation. For the same reason, the Decades is a valuable repository of quotations from the early church fathers on all the major topics of theology.

The first decade treats the Word of God and faith. Among other things, Bullinger gives a biblical-theological survey of revelation from Adam to Christ and the apostles. Unusual among Reformers, he includes a sermon on hermeneutical methodology (I.3)—something modeled rather than explicitly stated in most Reformation writings. His treatment of justification (I.6) is a classic defense, and a much-needed corrective to some modern restatements, of this cardinal Reformation doctrine.

The second and third decades expound the ten commandments in a way that is solidly Reformed, reflecting helpfully on the place of ceremonial and judicial laws in the New Testament era. Bullinger’s treatment of the Sabbath Day was to be influential in later Puritan thought. Particularly worthy of note, however, are Bullinger’s four sermons (originally intended to be one) on the sixth commandment. Here we find an important summary of Reformed political thought as the author unpacks the relationship between church and state.

The fourth decade deals with grace and repentance, God’s providence and predestination, and God the Son and God the Holy Spirit. The fifth and final decade treats the doctrine of the Church, addressing some of the most controversial subjects of Bullinger’s day—the nature of the Church, the ministry, the means of grace, prayer, and the sacraments. Much space is given to asserting the proper interpretation of the words, “This is my body,” providing a clear illustration of Bullinger’s hermeneutical principles set out in I.3.

In keeping with the goal of the work, the tone of the Decades is intellectually rigorous, but at the same time is warmly pastoral. The Decades do what all theological writing should do—inform the mind, warm the heart, and lead the reader to worship.

Warren Peel | Trinity (Newtonabbey, N. Ireland) RPC