You have free articles remaining this month.

Subscribe to the RP Witness for full access to new articles and the complete archives.

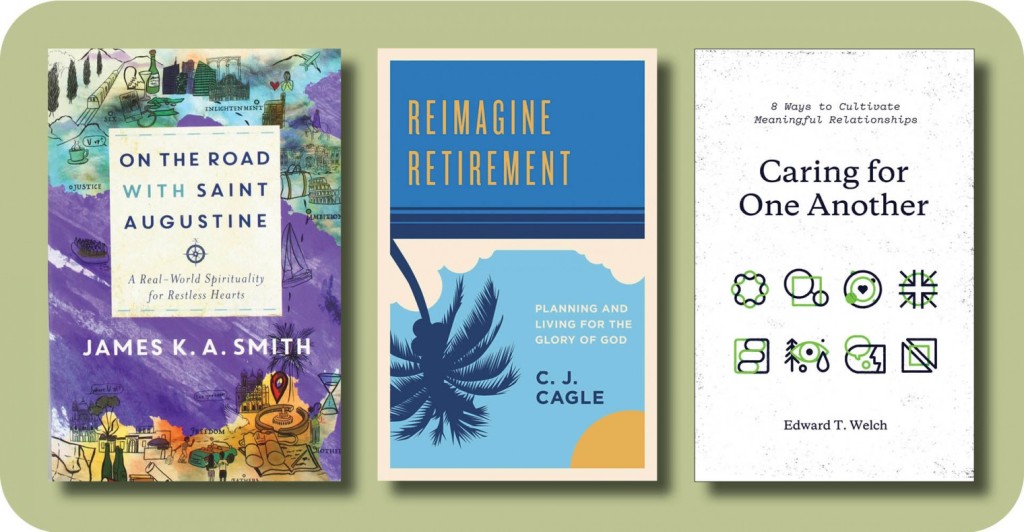

James K. A. Smith | Brazos Press | 2019, 256 pp., $24.99 | Reviewed by Fiona Buck

On the Road with Saint Augustine issues two warnings to the would-be reader, one on the back cover and one on the front. On the back cover, author James K. A. Smith announces, “This is not a book about Saint Augustine.” While the book offers snapshots of Augustine’s life and thought, they are intermingled in roughly equal proportion with biographical and philosophical snapshots of existentialists and of Smith himself. Thus, if you are looking for a readable biography about the bishop of Hippo or a neat volume highlighting Augustine’s main contributions to philosophy or theology, this is not the book for you.

The second warning is the subtitle: A Real-World Spirituality for Restless Hearts. Operating under the assumption that our culture (and therefore his reader) has been profoundly shaped by existentialism, Smith points to Augustine as someone who has wrestled with contemporary questions and problems. Unlike the existentialists, however, Augustine offers hope of finding rest because he knows the God who welcomes prodigals home. If you do not have an experiential understanding of spiritual restlessness—of looking for love and fulfillment in all the wrong places, of yearning for “something more” than what the world has to offer—then again, this is not the book for you.

As suggested by the title, On the Road is an invitation to travel with Augustine—to try on for size Augustine’s experience of having Christianity reorder his life. In the main portion of the book, the ensemble of characters—Augustine, the existentialists, and Smith—tackle 10 different topics: freedom, ambition, sex, mothers, friendship, enlightenment, story, justice, fathers, and death. Each essay-like chapter takes up one topic and, for the most part, includes the following: an account of Augustine’s pre-conversion approach to the issue; various existentialists’ wrestlings, which—though often similar to Augustine’s—fall short of a satisfying resolution; a few anecdotes from Smith’s own philosophical or physical journeys as he researched Augustine; and finally Augustine’s re-engagement with the issue after Christ reordered his understanding and affections.

Each chapter offers some insights. For example, in the chapter on death, Smith draws the lesson from Augustine that, to love rightly, we must love others in Christ, since then we can love without fear of loss. However, the main point of the book is simply Smith’s exhortation to travel with Augustine because he knows where home is.

Despite the scattered insights and Smith’s accessible and engaging style, I confess I was disappointed with the book. My disappointment did not stem from philosophical or theological disagreement (although at times I wished Smith would stop just suggesting that Augustine and Christianity might be right, and at other points Smith’s sacramental theology sounded more Roman Catholic than Protestant). Ironically, for all Smith’s evident effort to be relatable, my main complaint was the conclusion that I was not Smith’s intended audience. Smith states multiple times that he is writing to prodigals; but there are two sons in that parable, and Smith’s book is addressed only to the younger.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Reimagine Retirement

C.J. Cagle | B & H Publishing Group | 2019, 224 pp., $16.99 | Reviewed by Sam Spear

Americans are crazy about retirement. We think about it a lot. Can I retire? How can I afford to retire? Should I retire? Are golf and palm trees all they’re cracked up to be? Christians have additional questions. How does the Cultural Mandate apply in retirement? Should I even want to retire? Am I just storing up treasures on earth?

C.J. Cagle, MBA, deacon, and retired IT professional, works to provide some context and perspectives for these questions as well as show some tools to help develop answers. There are many tactical books that address the nuts and bolts of the finances of retirement, but they are burdened by an uncritical, underlying acceptance of secular retirement thinking. Cagle seeks to look at retirement from a Christian perspective—what to do, yes, but also what to avoid, what to pursue, and how we can glorify God in retirement.

At 200 pages, the book is readable but not skimpy. Cagle is informed by Christian thinkers including Randy Alcorn, John Piper, Larry Burkett, Ron Blue, and Dave Ramsey, but he is not subject to any of them. If you have read these authors on the subject of money, you will be glad for some of the current, practical instruction and tools that this author brings to the subject.

The first section of the book discusses the development of retirement thinking, from family support in agrarian America through the recent conception of FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early). It also addresses applicable biblical principles like work, rest, and stewardship, and offers a proposal of a model for a gospel-centered, God-glorifying retirement.

The middle section of the book deals with retirement planning—saving, investing, and evaluating your financial readiness. The last part of the book deals with several strategies for converting your assets into an income stream for your later years, how to think about productivity in retirement, and end-of-life concerns.

One especially helpful feature of the book is that Cagle provides a case study of a fictitious couple as they navigate the finances of a middle-class American family. Shifts in income, family size, and life circumstances in the case study make the financial matters more concrete and relatable. Charts, tables, and graphs also help to organize and relate the material. Each chapter ends with review questions, but the questions are presented for personal reflection, rather than for group study.

Reimagine Retirement doesn’t break much new ground, but it brings several threads together to make a pretty useful whole. If you need an introduction to the subject, want to polish up your planning, or want to evaluate whether your stance on retirement is biblically sound, then this book would be useful to you.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Caring for One Another

Edward T. Welch | Crossway, 2018, 80 pp., $9 | Reviewed by Meg Spear

Longtime biblical counselor Ed Welch has written an insightful little book focusing on ways to cultivate deeper relationships.

Surprisingly, it is intended to be read aloud in a group setting, propelling participants to grow in their ability to know and to care for each other. Because of this suggested format, chapters are only four or five pages long, and they conclude with questions to discuss as a group.

Although the methods he prescribes are not particularly revelatory, Welch’s presentation of them is quite helpful. He reminds the reader of Paul’s words in Ephesians 4, where undershepherds and teachers are called to carry out their ministry in equipping the saints to do the work of ministry. As believers, he therefore concludes, it is our calling to care for each other’s souls.

Welch wisely starts with the need to be humble. This humility should drive us to God in prayer, and it should cause us to ask for prayer from others as we face the troubles that are inherent to this life. Our personal willingness to be vulnerable helps set a tone of openness and humility in our relationships.

As we practice humility, we also need to move toward others. We listen compassionately and follow up with them, reaching out in Christian concern.

Welch encourages us to gently probe beyond the surface while avoiding painful, intrusive questions. He reminds us that external circumstances such as broken relationships or physical pain often impact the heart significantly.

He urges us to pray with each other spontaneously and regularly. He reminds us that we all suffer and that it is good to walk with other believers, to bear each other’s burdens, and to identify with the sufferings of many in the Bible. He encourages us to talk, albeit very carefully, about sin and to continually point to Christ for the answers to life’s questions and troubles.

“God uses ordinary people and their increasingly wise, childlike, God-dependent conversations to build his church. These do not depend on our brilliance in order to be helpful; they depend on Jesus, his strength, our weakness, and our humble response to him,” Welch writes. So may it be.